Throughout an accomplished career that spans more than 50 years, Vija Celmins (American, b. 1938) has sustained a practice of deep focus and extraordinary skill in a wide range of media.

Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory, the artist’s first major retrospective in more than 25 years, will be on view at The Met Breuer from September 24, 2019, through January 12, 2020. Celmins bases her paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints on the world around us—sometimes through direct observation but more often through what she calls “redescription,” a process of translating photographic images from one medium to another. Whether her sources are quotidian objects from her studio in Venice Beach, California, photographs of the Pacific Ocean or the desert floor, or found images from newspapers, magazines, and journals of scientific exploration and inquiry, the resulting work possesses a magical verisimilitude that compels the viewer to look more closely. The exhibition will celebrate the full range of the artist’s career from 1964 to the present through approximately 120 objects.

“Vija Celmins is one of the most important artists of the last sixty years, and her work feels especially timeless,” said Max Hollein, Director of The Met. “Celmins’s exquisite compositions invite us to stop, look, concentrate, and rediscover the world that surrounds us—and her—anew. We are thrilled to present this singular artist’s remarkable career here at The Met Breuer.”

Born in Riga, Latvia, Vija Celmins with her family fled the advances of the Soviet army near the end of World War II. They lived in refugee camps in Germany until immigrating to Indianapolis in 1948. After her graduation from college in Indiana, Celmins moved to the West Coast in 1962 to attend graduate school at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). She lived in Los Angeles until the early 1980s, when she moved to New York. Both cities have proved pivotal to her practice.

After her graduation from UCLA in 1964, Celmins began her first body of mature work: a series of still-lifes of objects from her studio, which she painted from direct observation at exact scale and against a neutral backdrop. These objects included “things that light up,” as she called them, such as Heater (1964) and Lamp #1 (1964). Depicting objects at hand provided a way for the artist to remove expressionistic composition, brushwork, and color from her work.

By the mid-1960s, as the Vietnam War escalated, memories of her childhood during the war returned and she turned to small-scale, detailed depictions of fires and of World War II bombers based on clippings she took from journals and magazines. Despite their diminutive size and deadpan execution, the works are powerful as emblems of a violent past and present.

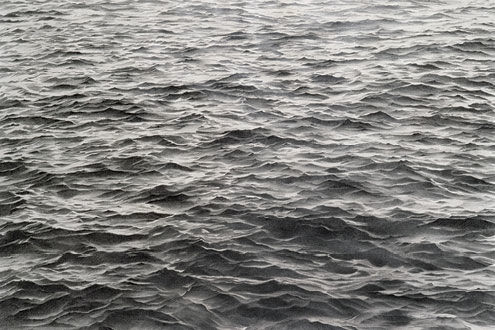

In 1968, Celmins began a series of works that used photographs she took of the Pacific Ocean near her studio in Venice Beach. It was a subject that would occupy her for nearly a decade as she stopped painting completely and turned to graphite as a more precise medium to document the surface of the ocean in detail. Each of the ocean drawings is an overall image of the sea, drawn from edge to edge with no horizon line or break in the surface. The resulting works merge the image with the surface of the paper and undercut the idea of the picture as a window into illusionistic space.

The exhibition also includes other subjects in graphite that display Celmins’s efforts to push the limits of her chosen medium further. Subsequent series include works made from 1969 through the mid-1970s that “redescribe” satellite imagery of galaxies, images from the Apollo lunar landing, and photographs of the desert floor.

In addition to drawings and paintings, Celmins has repeatedly returned to sculpture, focusing on ordinary objects, often using them to explore the concept of verisimilitude. For her work To Fix the Image in Memory I–XI (1977–83), which gives the exhibition its title, she used 11 found stones from trips to the desert in Arizona and New Mexico and had them cast in bronze. She then painted the bronze stones, creating “redescriptions” so precise that it is nearly impossible to tell the painted stones from the real ones—a process she has called “a work of meditation.” This work, which she carried with her in her move from Los Angeles to New York City in the early 1980s and finished once she arrived in New York, also represents the artist’s passage back to painting after a decade away from the medium.

In the 1990s, she turned her focus back to the night sky as her primary image, first in paint and then in charcoal. Unlike her drawings from the 1970s, where graphite strokes were layered on to build up her images of oceans and desert floors, the charcoal night skies began with layers of solid charcoal, which the artist carefully erased to map skeins of stars within the fields of gray and black. In 1993, Celmins found some images of spider webs in a scientific textbook and began using them in various paintings and drawings. Celmins says she liked the similarity of the flat picture plane and spider web.

In the past two decades, Celmins has expanded on earlier motifs and interests while incorporating meditations on memory and time. She has returned to painting objects found in her studio—the surface of a shell (Shell, 2009–10) or exterior of a book (Darwin, 2008–10), for example—painting them from direct observation. But unlike her earliest still-lifes, in these the surface of the objects extend to the edge of the canvas, filling the frame like her ocean, desert, night sky, and web paintings. In sculpture, Celmins has recently returned to the concept of verisimilitude that she first explored in the late 1970s with a series of works that precisely describe found slate chalkboards once used by schoolchildren. She continues her enigmatic mirroring of the made objects and found objects together in one work.

Though she has never been aligned with one particular style or medium, as this exhibition demonstrates, the many examples of Celmins’s work from her time in California and New York show the artist’s continued interest in representing the world around her. To Fix the Image in Memory brings together a luminous body of work in all media that demonstrates the ways in which Celmins’s practice is based on close looking and a sustained belief in making art.

Vija Celmins: To Fix the Image in Memory is co-curated by Ian Alteveer, Aaron I. Fleischman Curator, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met, and Gary Garrels, Elise S. Haas Senior Curator of Painting and Sculpture at SFMOMA, with Meredith A. Brown, Research Associate, Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at The Met and Nancy Lim, Assistant Curator, Department of Painting and Sculpture, SFMOMA.

Prior to its presentation at The Met Breuer, the exhibition debuted at SFMOMA, where it was on view December 15, 2018–March 31, 2019, and then traveled to the Art Gallery of Ontario, where it opened on May 4 and is on view through August 5, 2019.

#MetVijaCelmins.

Leave a Reply