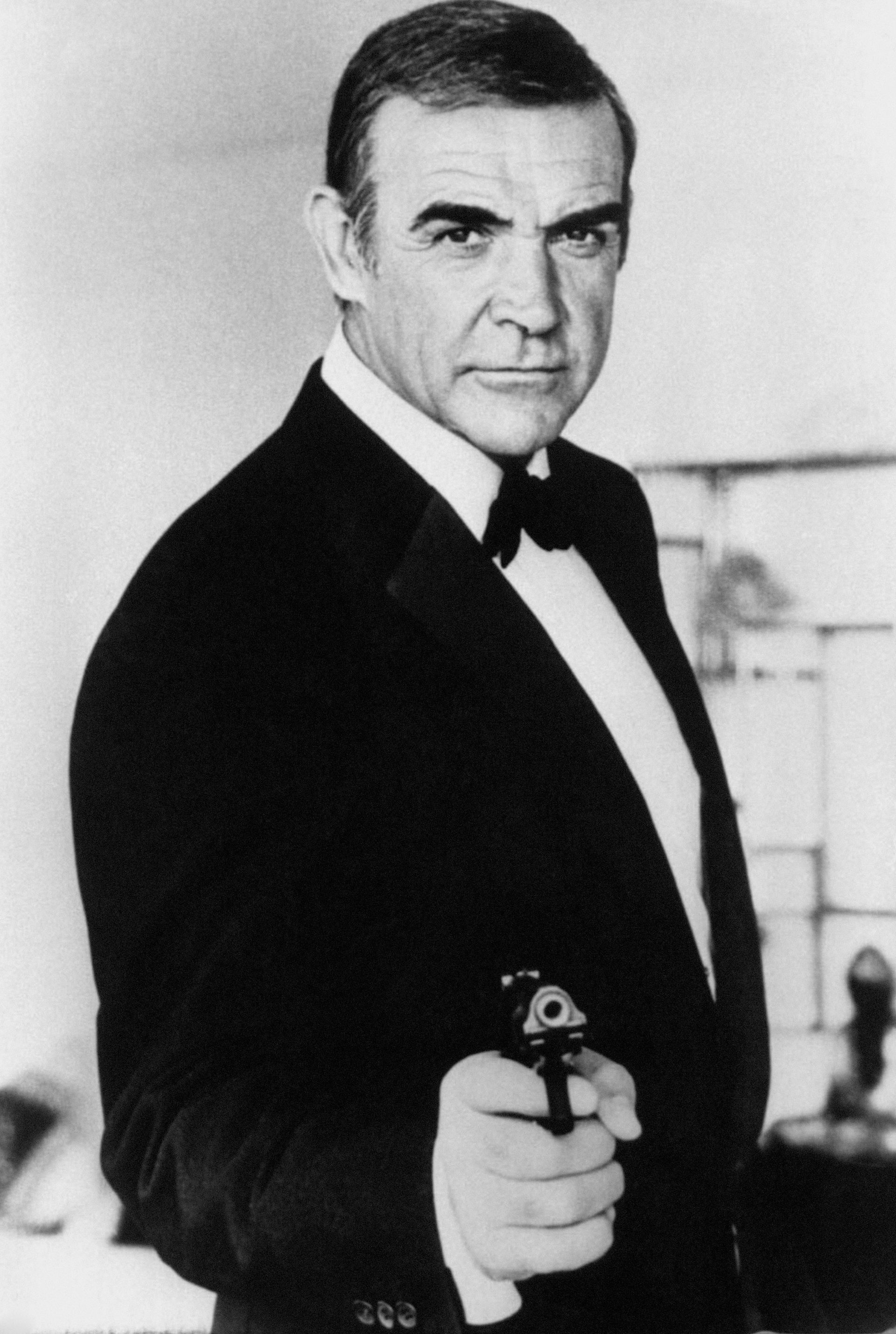

Coverage of the passing of Sir Sean Connery has inevitably been dominated by his legacy as the screen’s first – and best – James Bond. Connery’s “Bond, James Bond” moment near the beginning of Dr. No (1962) is one of the iconic moments of cinema history and has spawned countless imitations and parodies.

Perhaps the most persistent myth about Connery, who was 90, is that he was an “unknown” actor who was plucked from obscurity by Bond producers Albert “Cubby” Broccoli and Harry Saltzman, who reportedly cast him against the wishes of author Ian Fleming and distributor United Artists. But this is to ignore the fact that Connery had already established himself as a television actor, drawing critical plaudits for lead roles in a 1957 BBC production of Requiem for a Heavyweight and in the 1961 TV production of Anna Karenina, but also appearing in a number of meaty co-starring roles in Hollywood films, including opposite Lana Turner in Another Time, Another Place (1958).

It was reportedly his appearance in Disney’s fantasy Darby O’Gill and the Little People (1959) that drew Connery to the notice of Broccoli’s wife, Dana, while the British crime drama The Frightened City (1961), in which Connery as an underworld enforcer steals the picture from its nominal star John Gregson, was also evidence of a star in the making.

Nevertheless Connery was inspired casting as James Bond. Connery made the role his own to such an extent that it is now impossible to imagine any of the other actors said to have been considered – including Cary Grant, David Niven, Patrick McGoohan and even Roger Moore – stepping into the shoes of “the gentleman agent with the licence to kill” in 1962.

In this context an important point to remember about Bond is that Fleming’s character was not an Old Etonian establishment figure: he is even described in Moonraker as being “alien and unEnglish”. Connery’s working-class Scottish roots – he was born and grew up in Edinburgh, where his early jobs had included milkman, bricklayer and coffin-polisher – imbued his Bond with that sense of “otherness”.

To this extent Connery’s Bond has as much in common with the outsider protagonists of the British new wave – Laurence Harvey, Albert Finney, Richard Harris – as the tradition of British screen heroism incarnated by stars of the 1950s such as Richard Todd and Kenneth More.

Connery’s performance in Dr No is edgy and brusque: he really settled into the part in From Russia With Love (1963) and Goldfinger (1964) where he commands the screen with that indefinable quality of star “presence” that means all he has to do to dominate a scene is to be in it.

Beyond Bond

Bond brought Connery fame and fortune. He was paid a mere £6,000 for Dr No, four times that amount for From Russia With Love and a then-record US$1.25 million for his first Bond “comeback” in 1971’s Diamonds Are Forever (George Lazenby had taken the role for On Her Majesty’s Secret Service in 1969).

The lucrative remuneration meant that Connery was able to pick and choose his roles outside the Bond pictures. Indeed his non-Bond roles demonstrate just how versatile an actor Connery was. Alfred Hitchcock cast him against type as Tippi Hedren’s conflicted husband in Marnie (1964), and he excelled in two films for Sidney Lumet, as the rebel-with-a-cause in the hard-hitting military prison drama The Hill (1965) and as a vengeful policeman in the much underrated The Offence (1973).

Connery was particularly good at playing characters older than himself, including the potentate standing up to Teddy Roosevelt in The Wind and the Lion (1975) and an ageing Robin Hood reflecting on his own myth in the beautifully elegiac Robin and Marian (1976). He paired with Michael Caine as soldiers of fortune in 19th-century Afghanistan in The Man Who Would Be King (1975) and was one of the all-star cast of suspects in Sidney Lumet’s lavish adaptation of Murder on the Orient Express (1974).

There was, inevitably, the occasional left-field choice, but even the science-fiction oddity Zardoz (1973) now has something of a cult status. Connery famously said that he would “never” play Bond again after Diamonds Are Forever: hence the ironic title of his second Bond “comeback” Never Say Never Again (1983), a rival production outside the Eon Production series mounted by independent producer Kevin McClory.

Connery won his only Academy Award, a popular choice as Best Supporting Actor for his “Irish” street-cop in The Untouchables (1987), after which his career enjoyed a second wind as the world’s most bankable sexagenarian film star in a sequence of superior adventure and caper movies including The Hunt for Red October (1990), The Rock (1996) and Entrapment (1999).

By this time Connery’s refusal to disguise his accent had become something of a trademark, whatever the part. When Steven Spielberg cast him as Harrison Ford’s father in Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989), it captured the idea that Connery’s Bond was the symbolic “father” of a later generation screen hero.

Feet of clay

Most stars turn out to have feet of clay: Connery was no exception. He attracted controversy for a remark made in an interview with Playboy in 1965 that legitimised hitting a woman (“An open-handed slap is justified if all other alternatives fail”). His Bond did this on screen in From Russia With Love and Diamonds Are Forever.

He also had a public falling-out with Broccoli, suing the producer and MGM for alleged non-payment of profit shares in the Bond films. Against this should be set Connery’s charitable work: he used his fee for Diamonds Are Forever to found the Scottish International Education Trust to provide financial assistance for Scots from disadvantaged backgrounds to attend university and college.

Proud ‘Scottish peasant’

Connery, who since the 1970s lived in Spain and the Bahamas as a tax exile, was proud of his Scottish roots. Ian Fleming warmed to Connery to the extent that he introduced a Scottish heritage for Bond into the later stories. Bond’s “I am a Scottish peasant and I will always feel at home being a Scottish peasant” – from The Man With the Golden Gun – might have been written with Connery in mind, although Bond was actually played by his successor, Roger Moore, in that film.

Unlike Bond, Connery did accept a knighthood, for services to film drama, in 2000. It is widely believed that his public support for the Scottish National Party had delayed his knighthood.

Connery’s last screen appearance was as Allan Quatermain in The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen (2003), in which he leads a Victorian superhero team to save the British Empire. He confirmed his retirement when he was presented with the American Film Institute’s Lifetime Achievement Award in 2006.

He died in his sleep at his home in Nassau, and is survived by his second wife Micheline and son (by first wife Diane Cilento) Jason Connery.![]()

James Chapman, Professor of Film Studies, University of Leicester

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply