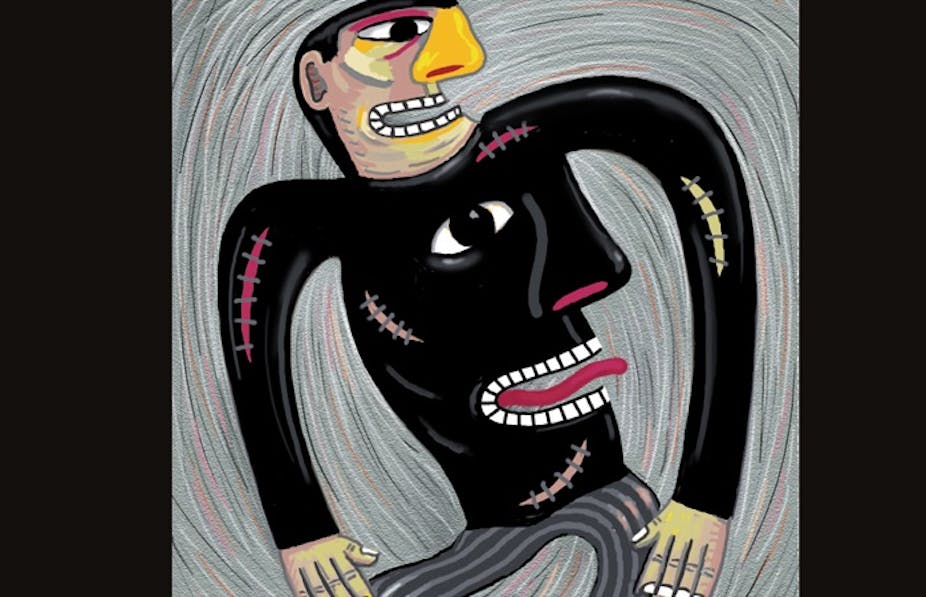

The cover of The Routledge Handbook of Critical Studies in Whiteness carries a striking image courtesy of South African artist Norman Catherine. The image was created in 2015 as one of a set of digital prints and, typical of Catherine’s work, contrasts dark and light to present a cynical view of the world informed by society and politics.

This image can be interpreted as expressing some of the ideas in the Handbook. It gives me a way to approach this book review because my teaching, research and writing deal with understanding how graphic images can convey ideas and carry meaning. I am not proposing that Catherine deliberately set out to visualise whiteness in his image, and acknowledge that my interpretation is my subjective opinion.

Titled “Show & Tell”, it shows a stylised male figure in profile, with slicked back black hair and a skin colour ranging from pale pink, green and grey to a hot magenta and shining yellow.

Catherine’s choice of skin colours illustrates the most obvious thing about people called white, and that is that they are not actually white. As noted by English academic Richard Dyer in his analysis of racial imagery of white people in his 1997 book White, white people are not literally nor symbolically white.

The figure’s profile lacks a forehead and is dominated by an enormous yellow nose and forward jutting chin, between which a grimacing mouth encircled by a row of blocky white teeth gapes. His black-clad torso is transformed into a similar profile, with glaring white teeth and a flapping pink tongue. I interpret the figure as showing what Dyer identified as “a divided nature and internal struggle between mind (God) and body (man)”, “a Manichean (dualism of black:white”, “the presence of the dark within the white man”).

Such a divided way of seeing and knowing the world contributed to centuries of racism and white supremacy that continues into the present with devastating impact. Challenging and dismantling racism and white supremacy is part of the purpose of the book, edited by academics Shona Hunter and Christi van der Westhuizen.

Critical Studies in Whiteness matter as it forms, in the words of the editors, part of a “broader project towards racial and social justice, and the end of heteropatriarchy and coloniality”. The editors describe whiteness as (page 3)

a dynamic, shifting, but durable system of domination through, under, against and within which people live, work, and relate.

Whiteness can be overt and highly visible, as was the case in apartheid South Africa, or operate invisibly. This book succeeds well in describing and criticising, through many examples, how whiteness works.

Whiteness across time and space

To make whiteness visible is a frequently stated goal of whiteness studies and this is shown on the cover in the clearly defined figure. However, Hunter and Van der Westhuizen argue in Chapter 1 that whiteness shifts between invisibility and visibility, to the point of becoming “hyper-visible”.

The arguments the editors make in their introductory chapter are complex, layered and not easily summarised. This is not surprising as the book is aimed at researchers, scholars and advanced students in a variety of academic fields.

The Handbook, consisting of 28 chapters, a preface and an epilogue, analyses the operation of whiteness across time and space. It does so through the contributions of a variety of scholars from various disciplinary, geographic and national contexts. A wide range of topics are covered from different perspectives. From histories of whiteness in India, Japan and South Africa, to a critique of trans-racial adoption in Sweden, and the harm done to grassroots organisations in the United States by foundations created by “white, corporate elitists”.

Contributions point to whiteness as being positioned at the heart of a “global colonial world system” and as being implicated with capitalist relations, heteronormativity – the belief that heterosexuality is the only natural expression of sexuality – and patriarchy. This is signified in Catherine’s figure with its pinstriped trousers and shiny black lace-ups.

Across the figure’s torso wounds strain against stitches through which various colours show, presumably of the skin beneath the black clothing. This brings to mind an objective of Critical Whiteness Studies which is identified by the editors as

dissect(ing) whiteness as a distinct power formation within the structures of race, racism, and white supremacy, that rose with and sustained colonialism, and today forms an essential part of coloniality (page xx).

The backlash

The inflicting of wounds on and sustained critique of whiteness has, however, not been without counterattacks. The wounded figure responds angrily, mouthing off, dynamic lines swirling around him, indicating that he has been forcefully lashing out.

The defence of whiteness is visible in the rise of the Alt-Right, neo-fascism and various forms of nationalism in recent years. The volume contains incisive critiques of such phenomena. This includes the backlash against feminism — in the form of the active promotion of traditional femininity through #TradCulture — and the embracing of whiteness as a form of resistance by the Alt-Right.

The rise of such phenomena underscores the fact that the social justice and anti-racist intent of the volume is now needed more than ever. While aimed at an academic audience, many of the chapters are very readable and I hope it finds a broader audience as the arguments it contains must be more widely debated.![]()

Deirdre Pretorius, Associate Professor in the Graphic Design Department, University of Johannesburg

Leave a Reply