In the lush hills of Malibu, California, green from a fresh bout of winter rain, a rail-thin man had just wet himself. It was January 2016 and the character, illustrated by artist Julien Ceccaldi, stood grinning at the entrance to Paramount Ranch – a Western saloon town movie set – as he peed his pants in excitement. Ceccaldi drew the cartoon avatar for the Paramount Ranch Art Fair, then in its third and final edition: The following year, the whole place would burn down in a catastrophic fire. It was a dramatic end fit for anime, though like a ghoul, Ceccaldi’s emaciated figure straggled on. With his jutting ribs, long, greasy locks and receding hairline, he continued to appear across the artist’s paintings, drawings, sculptures, and even merchandise – often lovelorn, and always a little bit lost. A masochistic survivor, he flung himself from one heartbreak to the next.

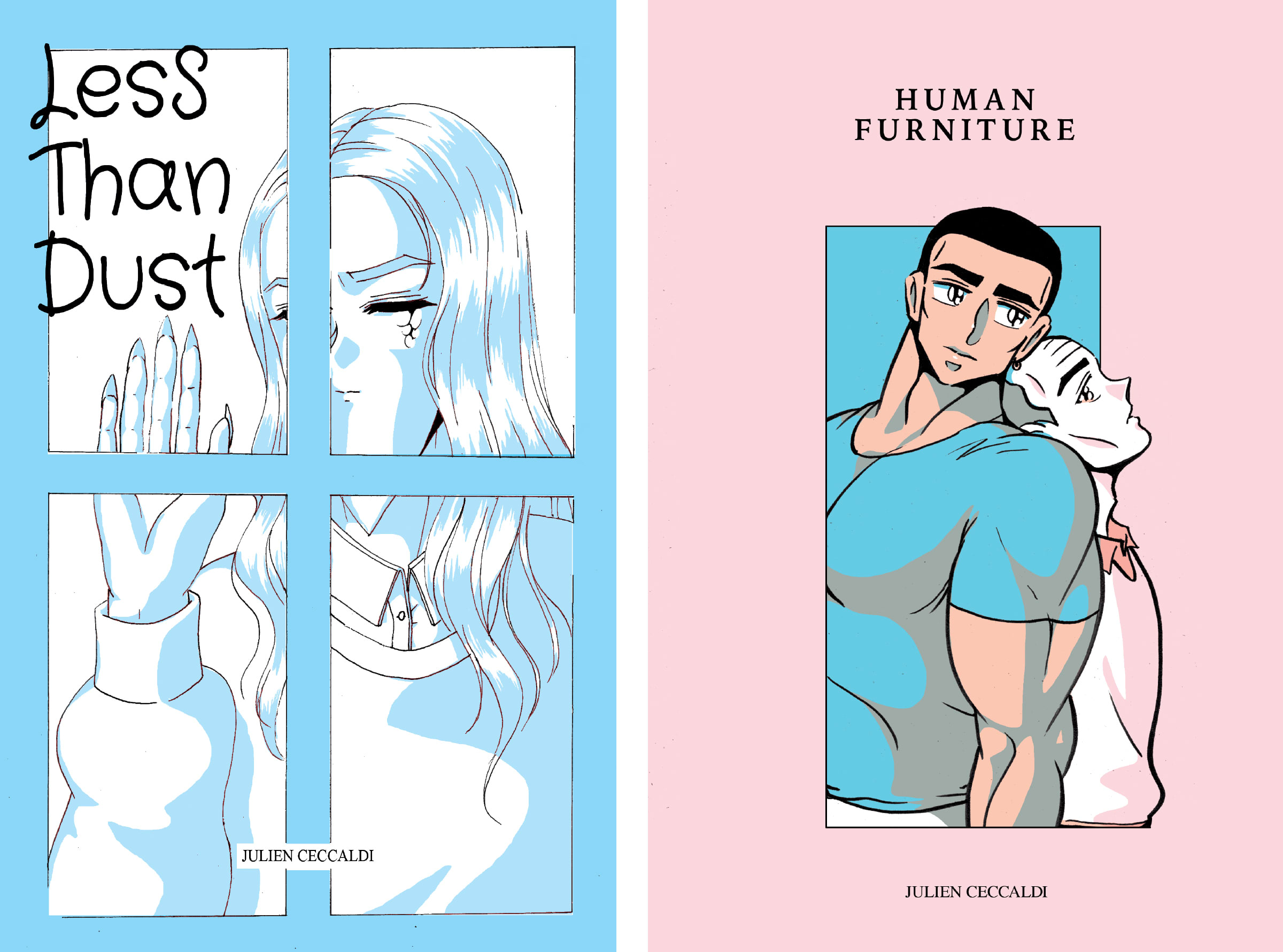

Ceccaldi first gained international recognition for a very different kind of figures: the brawny women with razor-sharp jawlines and horny, pig-faced men from his narrative comic Less than Dust (2014), who appeared on the Summer 2014 cover of Artforum. Crisply rendered in bright primary colors, with oversized eyes and tiny mouths reminiscent of Japanese manga, Ceccaldi describes them as ‘muscle girls who look like they have it all, but don’t’ – as though the bigger and tougher their exteriors, the more anemic their self-confidence. Stuck in a loop of unrequited love and retail therapy, Ceccaldi’s characters are always on edge, where that one reminder of their ex or being left on read could send them spiraling towards a meltdown. If this sounds relatable, their exaggerated figures magnify millennial anxieties until they’re so absurd, we can’t help but laugh at them.

Ceccaldi was born in Montreal, Canada, where he first nurtured his lifelong obsession with Japanese animation. When he was five years old, he fell in love with Rainbow Brite (1984-1986), the TV series produced by Hallmark and Japanese illustrators. Japanese coproductions were popular in Europe and North America then, as the influence of anime followed the global craze for video game technology. Ceccaldi devoured the Japanese cartoon series syndicated on Quebecois TV, such as Sally the Witch (1966-1967) and The Mysterious Cities of Gold (1982-1983). He developed a passion for drawing Disney princesses and, eventually, his favorite anime characters.

At age seven, he moved to Senlis, France, a medieval town built around an ancient castle and Gothic cathedral. It must have seemed like a fantasy animation come to life. At the local arcade there, he mastered video games such as Sonic, Streetfighter, and Final Fantasy, and read about manga in Spotlight, a video game magazine. On French TV, the weekly kids’ program Club Dorothée (1987-1997) ran American-style sitcoms back-to-back with Japanese anime shows like Dragon Ball Z, Sailor Moon, and Maison Ikkoku. Anime and manga were at once more fantastical and more honest about real human foibles than Western programs; they weren’t afraid to show sex and death.

A decade later, Ceccaldi had refined a manga-inspired drawing style, but he didn’t think it would be possible to incorporate it into a fine art practice until he encountered the work of Superflat artists Takashi Murakami and Yoshitomo Nara. My Lonesome Cowboy (1998), Murakami’s life-sized sculpture of a male character resembling Goku from Dragon Ball Z, exuberantly swinging a lasso of his own semen, was proof that anime could inform a new kind of Pop art. The work was, Ceccaldi recalls, ‘both original and referential, because it existed for itself and not as an extension of a brand or narrative universe.’ Inspired, Ceccaldi enrolled at Concordia University in Montreal to study art, and took a job at the store of Drawn & Quarterly, Canada’s premier comic book publisher.

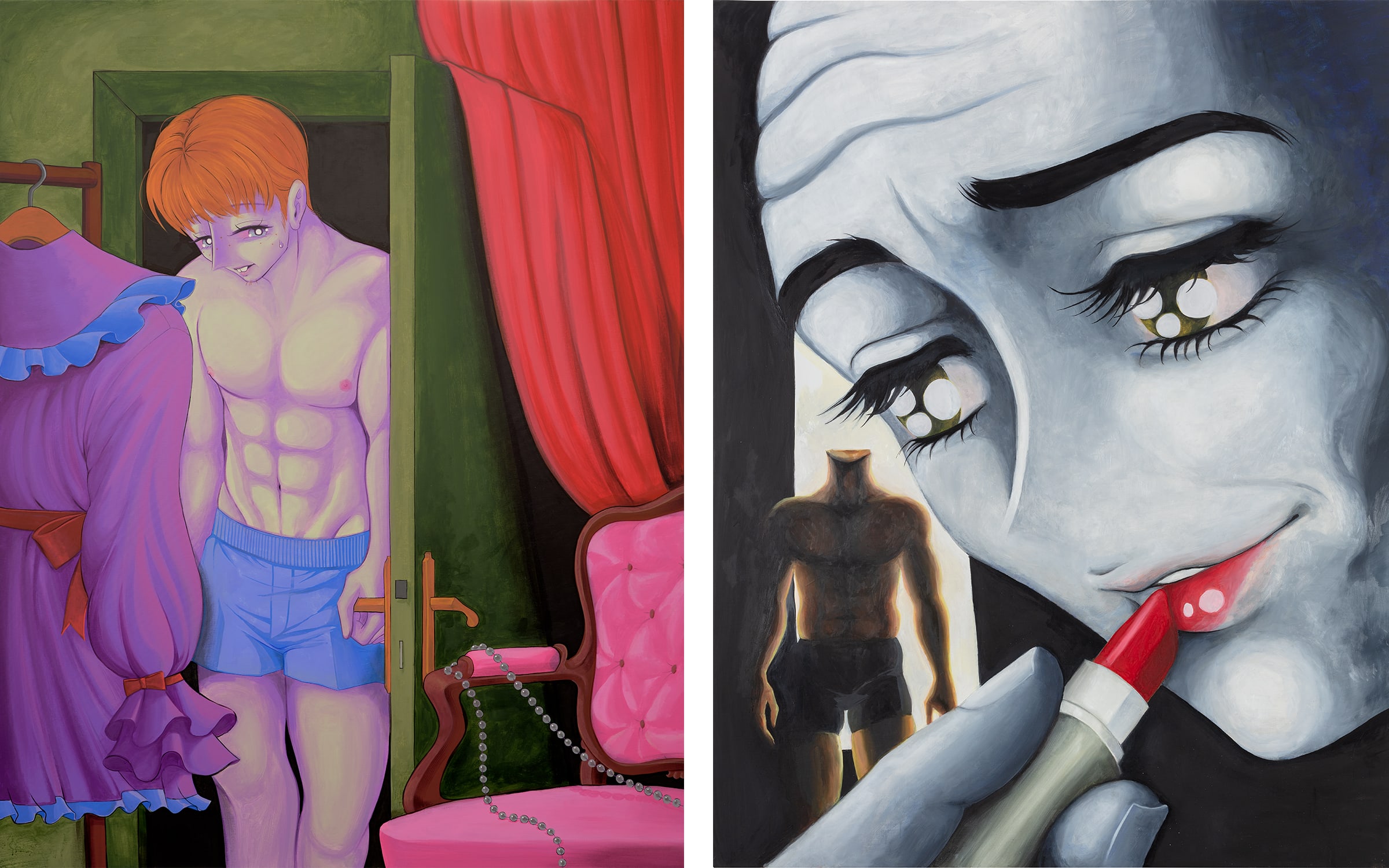

Most of Ceccaldi’s output was, and remains, without a fully legible narrative. Parallel or overlapping box frames in a single drawing might suggest a degree of simultaneity, as they do in manga or medieval painting, but without text we’re not always able to piece them together. This is by design. Ceccaldi manipulates his scenes in ways that both enhance their surrealism and heighten their emotional pitch. Major shifts in scale between figures increase the imbalances of power between them: in several works, his incontinent wraith, shrunk down to Lilliputian size, clings pathetically to the bulging bicep of a sweaty meathead. ‘I always add an aspect of distortion or freeze-frame that can only be achieved with drawing or painting, and wouldn’t be possible with photography,’ Ceccaldi says.

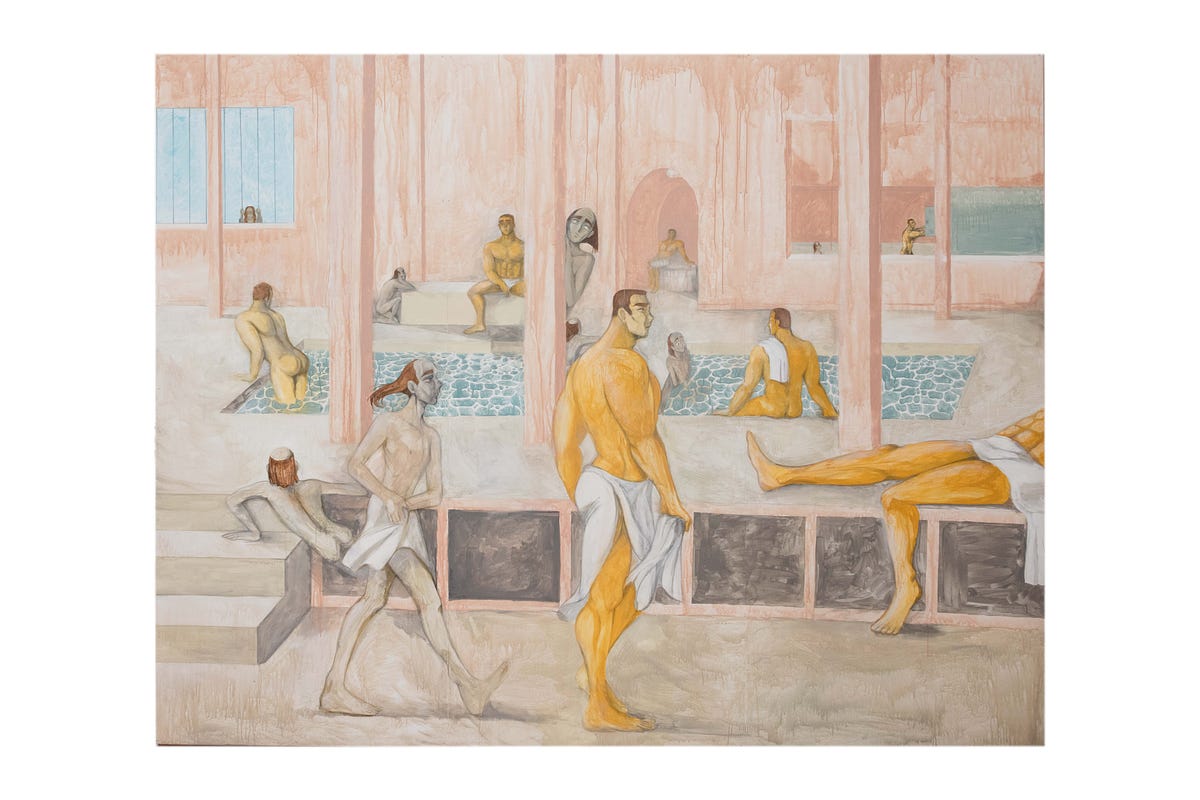

That skinny simp from Paramount Ranch is often multiplied across the single frame of Ceccaldi’s drawings and paintings, as if to underscore a sense of sexual desperation. See, for instance, how he lurks around every muscled hunk in the homoerotic Pompeii Bathhouse (2017). He cowers behind a cash register in An Obnoxious Customer (2021), whose titular figure, a buff pink shopper with a phallic snout, showers him rudely with credit cards. In Ceccaldi’s semi-autobiographical comic, Human Furniture (2017), his name is Francis, and he lusts for his studly ex, Simon, whom he runs into at a hot nightclub, where his ‘teardrops run down [Simon’s] meaty pectorals.’

Francis was partly inspired by a character from Chester Brown’s 1994 graphic novel, I Never Liked You, which Ceccaldi picked up at Drawn & Quarterly; there’s a dose of Riff Raff from The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) in him, too. But Ceccaldi was also intrigued by the ‘bad boy’ meatheads of the 2009-2010 reality TV show Tool Academy who, when asked to draw self-portraits, rendered themselves as vulnerable weaklings inside. In Ceccaldi’s world, as in ours, looks can be deceiving.

That’s a central theme of the European fairytales Ceccaldi has lately been adapting to his manga-inspired painting style, like a tour of Senlis by way of Tokyo. Characters morph into insects in paintings that recall the Brothers Grimm. In Ceccaldi’s 2019 exhibition, ‘Sex Is Work’, at Gaga, Mexico City, one painting (and a painted punch bag) depicted Francis as a spider, hovering over a bodybuilder’s magnified crotch. Another imagined him floating through the air towards an ornate Bavarian castle. In the spirit of European Surrealism, Ceccaldi’s distortions make familiar objects feel uncanny: for example, in one painting, a purple, Francis-like figure cuts into an iPhone as if it were a slice of cake.

Leave a Reply