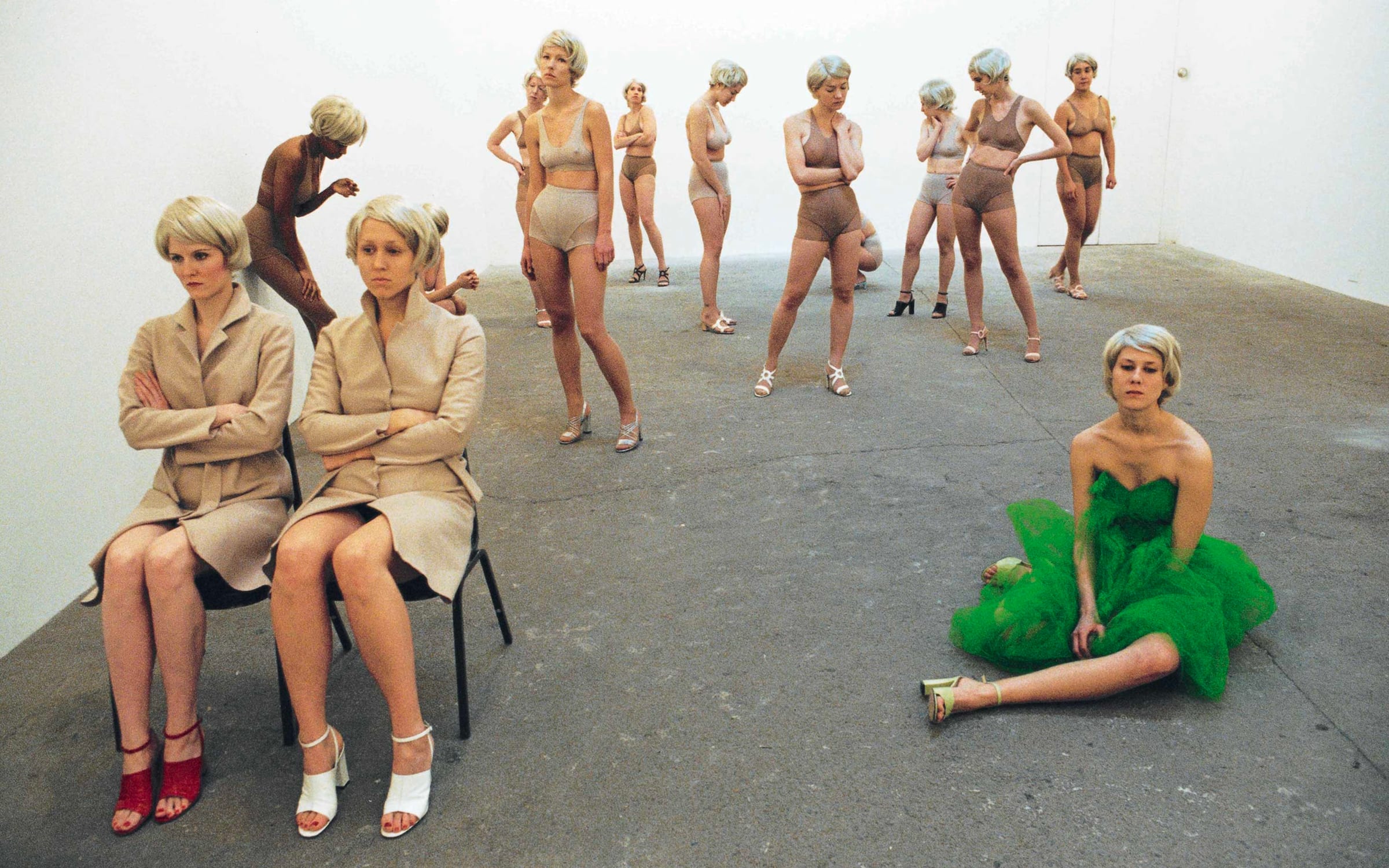

For the fifth installment of Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou’s series of interviews on iconic exhibitions in commercial galleries, the curator-duo talk to gallerist Jeffrey Deitch about the Vanessa Beecroft performance that launched his New York gallery in 1996.

Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou: You launched your gallery on Grand Street in New York in 1996 with a celebrated performance by Vanessa Beecroft: VB16 Piano Americano-Beige. How did you first meet Vanessa, and how did the idea for the performance come up?

Jeffrey Deitch: It was 1995 when I read a short review of a project called ‘A Blonde Dream’ that Vanessa Beecroft presented at a German gallery. After some back and forth, she agreed to stage the first show at my gallery, and showed a brilliant project called Piano Americano. It was Christmas, with all the holiday disruptions, and it was a kind of miracle that it all came together.

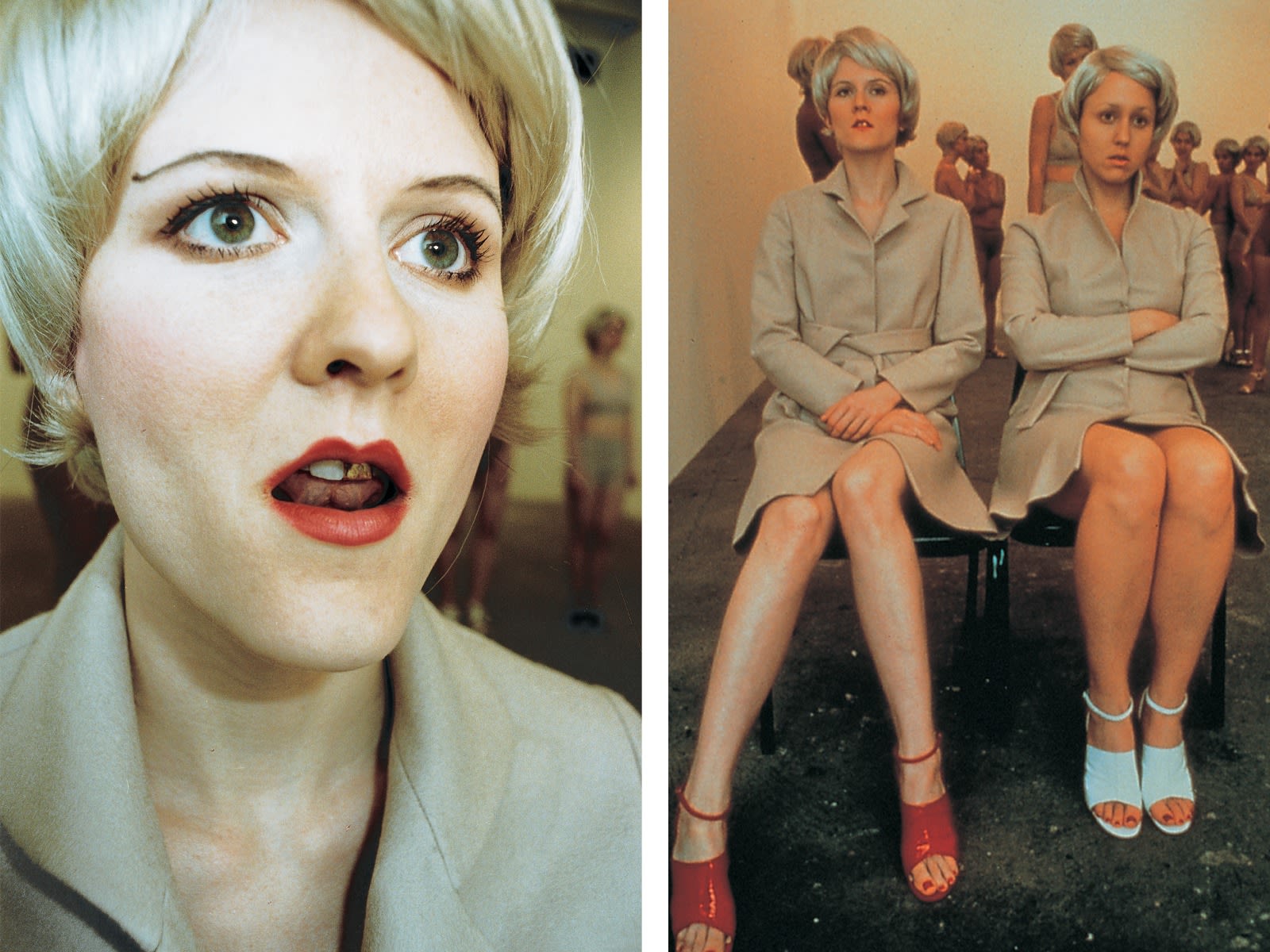

Vanessa conceived the entire choreography for the performance and created the costumes. She found seamstresses to make these colored bras, girdles, and nylon stockings that were the germination of what later became Kim Kardashian’s SKIMS clothing line.

I remember how precise she was. For the casting, we placed ads in the newspaper and on the day of the audition we were hit by one of the worst snowstorms in New York’s history. Traffic was paralyzed and I thought nobody would show up. Vanessa rejected the first people who came because they didn’t fit exactly what she had in mind. With this snowstorm, I thought that she should just take whoever showed up, but she persisted with her rigorous selection process and finally several dozen people came to the audition. It was quite a lesson for me; in Vanessa’s incorruptible vision – and in the determination of young people wanting to make it in New York as performers. In the end, she very systematically auditioned everybody and cast the perfect ensemble. After this selection process, we had these performers just wearing underwear in a freezing space. This was the second week of January and they did not even complain, they just stayed in formation.

Vanessa’s concept was fascinating; she did not direct the performers like a conventional choreographer but gave them a set of instructions, a bit like Sol LeWitt. Her performance was influenced by conceptual art. Among the instructions were sentences like ‘don’t walk too fast’ and ‘f you’re tired, you can sit down.’ She let people be themselves. At the same time, it was fascinating to see the gestures that the young performers had somehow absorbed: a lot of images from art history. In that performance, their gestures reminded you of sculptures by Bernini, Canova, or Rodin – like tableaux vivants. Many of the most influential people in the New York art world were there to see this show. Ultimately, I am proud to say that Vanessa’s career in the United States was launched in my gallery.

In the performance there is a sense of immobility, of muteness which is almost robotic. Do you make a connection between VB16 Piano Americano-Beige and the 1992 group show ‘Post Human’ that you curated at the FAE Musée d’art Contemporain, Lausanne [and which traveled to Castello di Rivoli, Turin; the Deichtorhallen, Hamburg; the Deste Foundation, Athens; and the Israel Museum, Jerusalem]? Could we describe her performance as a post-human living painting or post-human gesture?

Absolutely. Yes. I think there is a direct connection between ‘Post Human’ and Vanessa’s performance. In fact, this taste for performance and the post-human goes back to my first exhibition in 1975, where artists used their own lives and own bodies as an art medium. ‘Post Human’ was very influential in Italy and went to the Castello di Rivoli which at the time was probably one of the major European contemporary art museums. Maybe Vanessa directly experienced it or absorbed it through her partner, Miltos Manetas, who knew me very well. There is also a connection with the second show I did in my space on Grand Street: ‘Alien at Rest’ by the artist Jocelyn Taylor, where she walked naked in the street. The two performances work differently but share a lot of similarities; both women assert their power in a public space, both are strongly feminist in their concept and execution.

Could we say that your interest in Vanessa Beecroft – and also your program in general – had been nurtured by your early experience with the conceptual art scene?

Indeed. My first real job in the art world was as an assistant at the John Weber Gallery. It represented great minimal and conceptual artists such as Hans Haacke. But my most important mentor was Sol LeWitt; I had many conversations with him as well as with Hans. They were very tough-minded artists and they helped shape my understanding of art. Daniel Buren was another influential figure for me. I participated in his famous performance Seven Ballets in Manhattan (1975), carrying placards with stripes around Times Square. I was just the gallery assistant, but these artists would invite me to their studios to follow them around and be with them in the evenings. Let’s say it was my hardcore education.

At the beginning of its Grand Street era, your gallery seemed to embody the Greenbergian nightmare of an unholy alliance between avant-garde and kitsch.

I would say that a lot has changed in the art world since Greenberg wrote Avant-Garde and Kitsch in the late 30s. The New York School generation had to fight hard against middlebrow, against kitsch. They had to fight to be taken seriously. And this fight against the American middlebrow extended through minimalism and conceptualism. Then the 80s happened, where the boundaries between popular culture and fine art collapsed. Of course, it started with Pop Art and Andy Warhol, but by the 80s it had really penetrated society as a whole. This period has influenced what I do with my program up to this day. It involves a different kind of relationship between avant-garde and kitsch. Instead of opposing each other, I believe that they are in a constant fascinating dialogue. Fewer barriers between progressive popular culture and fine art produce a fertile ground for creation, even if artists and galleries need to be careful that the pop culture side doesn’t cannibalize everything.

Curator-duo Pierre-Alexandre Mateos and Charles Teyssou organized the Conversations program for the inaugural edition of Paris+ par Art Basel in 2022.

Leave a Reply