Geoffrey Hinton, the ‘Godfather of AI,’ recently predicted that so-called general artificial intelligence could emerge within 20 years. This term refers to a hypothetical future AI that can perform any cognitive task that a human can. This statement begs the question: how long will it take before we see the emergence of general artistic intelligence? And what should such hypothetical general artistic AI be capable of?

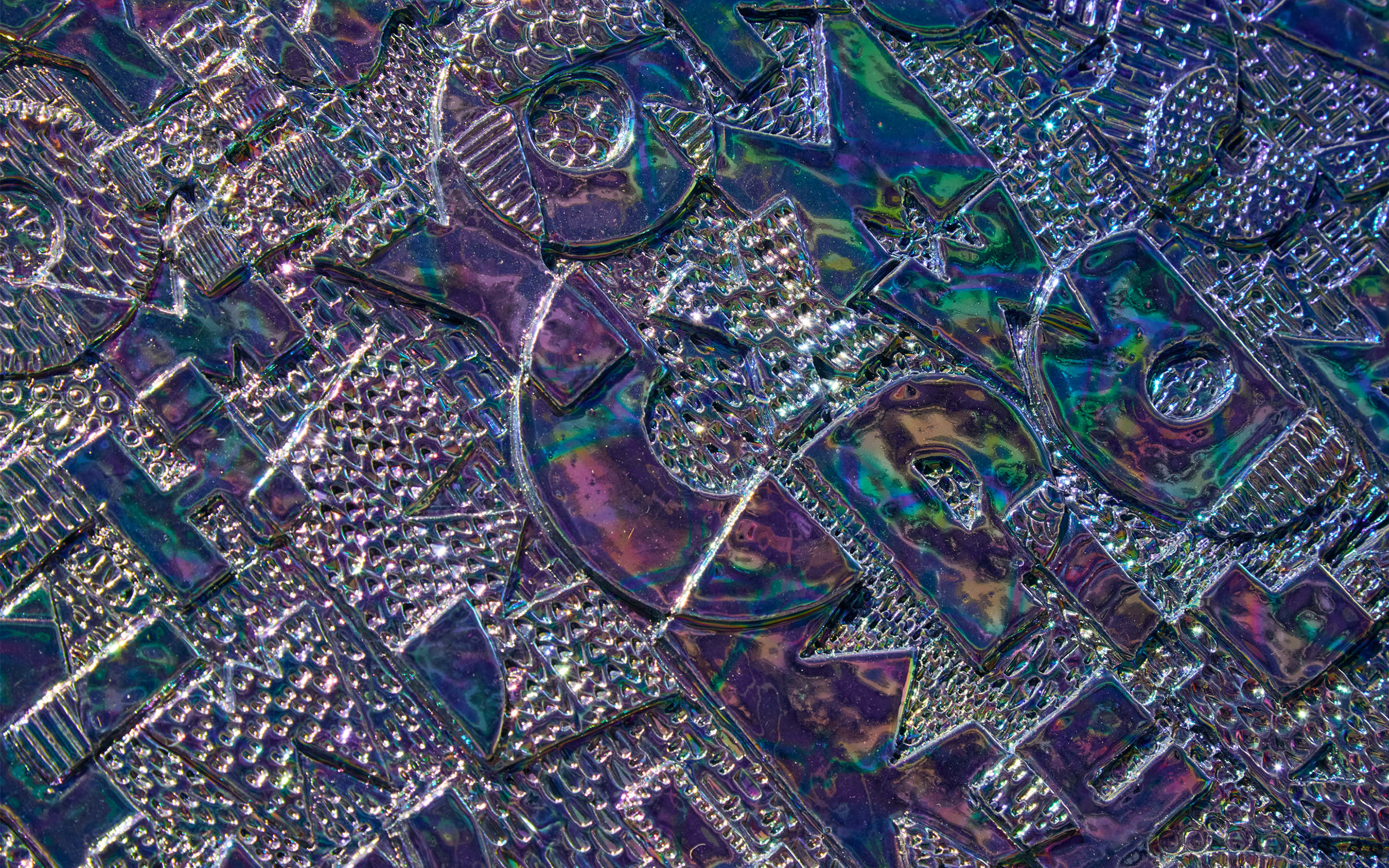

The current more limited paradigm for creating artistic works with AI is known as ‘generative media.’ (Not to be confused with ‘generative art.’) Trained on hundreds of billions of images and their text descriptions, this more limited AI learns to predict a probable image when you give it some text. The images it generates did not exist before, and depending on the prompt you provide, they can look either stereotypical or be quite unique. And if the artist is using Midjourney (currently the most advanced AI image tool), generated images are often aesthetically pleasing. They can have perfectly balanced compositions, beautiful color palettes, and lines and shapes forming rhythmical patterns.

So, while we can endlessly debate if AI is ‘creative’ or not, it is already fully ‘professional’; technically more accomplished than many art students and adult artists. Having taught in university art departments for 20 years, I am also certain that an applicant with a portfolio of only AI-generated images and an artist statement written by ChatGPT will be admitted to most art programs. In fact, this already is a real issue for art faculty who serve on admission committees.

Classicism and kitsch

Despite these amazing feats, AI image tools have significant limitations. A neural network does not understand what it generates. It has no knowledge of the world, or history or contemporary culture. It can’t evaluate its own creations or judge what is interesting and what is banal. Neural networks learn to extract common patterns from their training data and ignore rare artifacts, so they are better at making conventional rather than unique things. Often AI takes my descriptions of strange, uncanny, surreal, or absurd compositions and generates instead commonplace and predictable scenes. Sometimes I can get images that are closer to my intentions, but often I need to give up and try a new idea.

In the context of art history, the default representations generated by visual AI tools can be compared to classicism. These tools tend to synthesize idealized and flawless images. This becomes obvious when I use prompts that are just one word, like ‘sky.’ The generated Midjourney images display a true visual drama with large swirling expressive clouds in the center of the composition, rendered with rich saturated colors, as opposed to a flat blue sky with a few light clouds. These clouds could have been produced in Photoshop by a skilled commercial photographer today, a Salon artist from the 19th century, or a Renaissance architect. The outcome would be very different if a tool averaged all sky photos in its training data instead.

Another way to interpret the aesthetics preferred by AI image tools is to use the term ‘kitsch.’ Kitsch emerged in the art markets of Munich in the 1860s and 1870s as a term to describe inexpensive and popular pictures. According to Tomas Kulka’s analysis in his book Kitsch and Art (1996): ‘Kitsch depicts a beautiful or highly emotionally charged subject; The depicted subject is instantly and effortlessly identifiable; Kitsch does not enrich our associations related to the depicted subject.’ Kitsch, in other words, is melodramatic, shows only stereotypes, and lacks originality. This, to me, is an excellent description of the default images produced by AI tools. It is possible to make them not kitsch looking, but it takes time and prior experience in a field such as illustration or photography.

The art of the copy

AI image generation can be referred to as ‘the art of copying.’ There are four distinct types of copying going on. Firstly, you can endlessly repeat the generation process by running the same text prompt, hoping to see improvements from the original image. Many artists reported using the same prompt thousands of times until they got the desired images. Secondly, there are websites that collect millions of prompts and resulting images, so you can directly copy any such prompts, and then modify them. Thirdly, in the Midjourney default mode, you can view in real time thousands of other users entering their prompts and the images they produce, and others can view your prompts and images as well. Finally, AI image generation is ‘the art of the copy’ in the sense that many prompts refer to popular video games, Hollywood films, animation studios, and popular illustrators and artists.

What differentiates this AI-enabled ‘art of the copy’ from, for example, the millions of amateur artists creating copies of anime characters and uploading them on ArtStation and DeviantArt? One new aspect is the mechanism of copying. Instead of tracing over existing images by hand, as artists used to do, you can now copy text prompts which act as a ‘code’ for an AI image tool. Another new aspect is the modularity of the prompts. You can copy only words describing the aesthetics, composition, a feature or character, type of lighting, and so on, and then remix it with your own content description.

Before we dismiss vernacular AI visual culture as completely derivative and unauthentic, consider how important copying has always been in human cultures. Historically, image making was often about making copies or variations. For example, Bruegel’s family produced approximately 127 copies of his painting Winter Landscape with Skaters and Bird Trap (1565). According to political economist Krzysztof Pelc, ‘half of all commissioned artworks in the 16th century were copies of originals.’

In my opinion, museums that present the history of art through the lens of Modernism and emphasize uniqueness and originality do not allow us to fully appreciate the importance of copying historically. You can enter a room devoted to art from a specific time and place yet see a multitude of contrasting styles and approaches. This sampling bias toward uniqueness does not reflect the culture of copies and minor variations. The universe of AI imagery created by amateurs today reminds us of how cultures have always operated: through constant imitation and small modifications.

In conclusion, I want to come back to my opening question: what do we want to see in a hypothetical general artistic AI? While image generation tools will continue to improve, I want an AI that does not make any art on its own. Instead, this AI would use algorithms to analyze an artist’s works and provide them with insights and new ideas. It could visualize changing patterns in the artworks made over time in subject and form and suggest possible directions for experiments. It could identify which techniques the artist employs frequently and infrequently and encourage the use of more uncommon ones. In other words, even though such AI wouldn’t automate the creation of art (and why would we want this anyway?), it could offer artists something more valuable: intelligent feedback and even dialog.

This article is the first in a new series in which Art Basel asks thinkers and theorists to analyze the impact of new technology on contemporary art making.

Dr. Lev Manovich is a visual artist, writer, and one of the world’s most influential digital culture theorists. He was included in the lists of ‘25 People Shaping the Future of Design’ (Complex, 2013) and ‘50 Most Interesting People Building the Future’ (Verge, 2014). Manovich is a Presidential Professor at The Graduate Center, City University of New York, and a Director of the Cultural Analytics Lab. He has published 180 articles and 15 books including AI Aesthetics, Cultural Analytics, Instagram and Contemporary Image, and The Language of New Media described as ‘the most suggestive and broad-ranging media history since Marshall McLuhan.’ His digital art projects were shown in eight personal and 120 international group exhibitions including at the Centre Pompidou, ICA London, ZKM, KIASMA, and other leading venues.

Leave a Reply