Artists don’t just make art: They venture far and wide. And few of these forays have been more fruitful than when they take them to the stage. The history of painters and sculptors designing sets and costumes for opera and dance is exceptionally rich. Impresario extraordinaire Sergei Diaghilev set the tone at the turn of the 20th century for Les Ballets Russes by bringing together Coco Chanel, Jean Cocteau, and Pablo Picasso with the choreographer Bronislava Nijinska. Countless others followed, among them Sonia Delaunay, David Hockney, and Henry Moore.

Tacita Dean’s collaboration with choreographer Wayne McGregor and composer Thomas Adès on The Dante Project is inscribed in this lineage. First presented in full at the Royal Opera House in London in 2021, the dance piece is a reinterpretation of Dante Alighieri’s epic medieval poem the Divine Comedy (c. 1308–1321). It follows the young Dante as he journeys through hell, purgatory, and, finally, paradise, guided by the classical poet Virgil and his ethereal muse Beatrice.

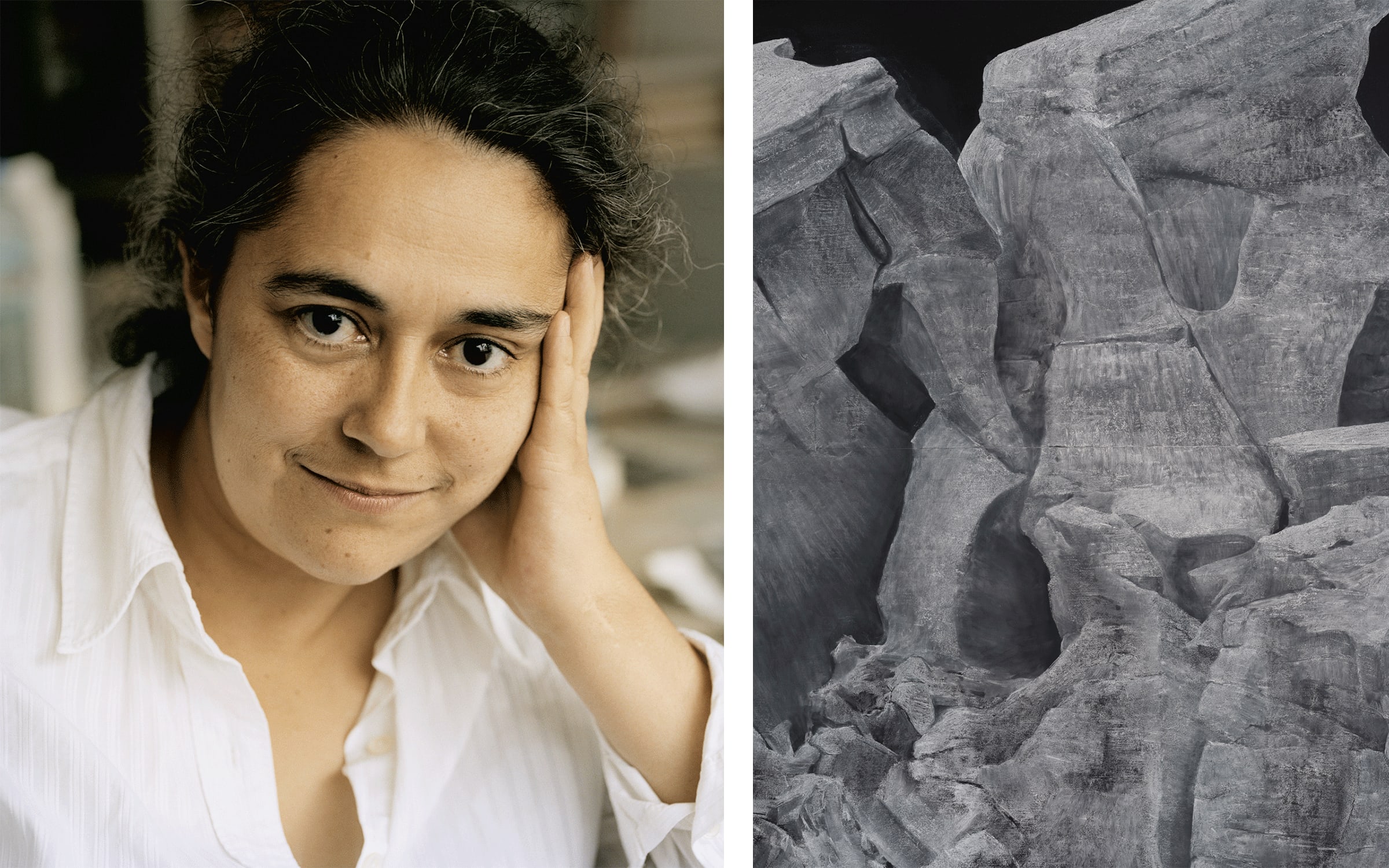

The Dante Project is Dean’s first venture into the world of dance. The artist, who is best known for her love of analog media, has just opened a show of new works at La Bourse de Commerce in Paris. ‘Geography Biography’ is the latest in a string of prestigious exhibitions that have marked her 30-year career, from London’s National Gallery (2018) to Paris’s Centre Pompidou (2018) and New York’s New Museum (2012). One month before the launch of ‘Geography Biography’ at La Bourse de Commerce, The Dante Project opened at Opera Garnier, also in Paris, where a new cast performed the initiatory journey under Marc Chagall’s iconic painted ceiling. The piece will soon come back to London, where the Royal Ballet will revive it at The Royal Opera House in Covent Garden, London, from November 18th to December 2nd, 2023.

In this interview – the second in a new series that revisits the Art Basel Conversations topic of ‘The Artist as …’, which looked at artists’ activities beyond the visual arts – Dean delves into her collaboration with McGregor and Adès.

How did The Dante Project come about? At what point did you join the team?

Wayne invited me. He and Tom had decided to explore an idea based on Dante’s Divine Comedy – and because it was Wayne and Tom, and because it was Dante, I said yes. So, I have been involved from the beginning, more or less.

Did they come to you with the music and the choreography?

Oh no, there was nothing at first. In fact, I created my designs before seeing any choreography or hearing any music.

You’d never done stage or costume design before, and you had very little to go on apart from the Divine Comedy itself.

Yes – and I was lost. Most designers work with an existing score but, in this case, Tom was still composing the music while I worked on the set. Choreography generally comes last. In the end, I found my feet just by sticking to my own approach and not trying to imagine how a scenographer would go about it. I made what I wanted to make as an artist: a drawing, a photograph, and a film.

In the first act, Inferno, the set is an enormous chalk drawing. Then, in the second act, Purgatorio, there is a photograph of a tree. The final act, Paradiso, features an abstract film. The three pillars of your visual art practice unfold alongside the choreography itself.

I decided to use different media because I wanted each of the parts to be very different visually. The three acts have distinct identities in terms of design, music, and choreography.

How much of a brief did you have?

The brief was, simply, ‘Dante.’ Originally, Tom was commissioned to write Inferno as the first act and Purgatorio and Paradiso as the second act. But I really thought it was important to have Purgatorio as its own act. Originally, I proposed to Wayne having silence for Purgatorio – just a moment of silence. Then, we discussed it with Tom, who suggested recorded sound. In the end, Tom used recorded sound as well as composed music for Purgatorio, which is a very important act.

In that way, it connected with the experience of the pandemic. For some people, it really was hell, but for most of us, it was a sort of purgatory. When the show eventually opened on October 14, 2021, we finally came to the release of paradise. It was an incredible feeling of freedom after the previous two years we’d all had.

Leave a Reply