Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960–88) was by most accounts a sweet kid. He had a baby face and a distinctive walk, one foot pigeon-toed, so he was easy to spot from a block away. He was a pussycat – at least the girls said so – soft-spoken and polite. And he liked to draw.

My mother-in-law, an art teacher who still lives on New York’s Upper West Side, had a different opinion about Jean-Michel after he and her son Danny [Danny Rosen], best friends from the alternative City-as-School high school, had an art-making session at her apartment that left a mess of glue on her Oriental rug. She’d asked the boys to clean up and they hadn’t, and the dismissive glance Jean-Michel gave her stuck in her memory.

That adolescent ‘don’t-bother-me’ negligence metamorphosed into an obsessive creative vision. As for the scraps the boys left behind – they no doubt were crafting postcards to sell outside the Museum of Modern Art – she dumped them into a box and later threw the whole lot out. Danny’s big sister Lisa, my wife, lost her Basquiat, too – one the artist had given her as a gift. They were friends from the punk-noir Mudd Club in Tribeca. Lisa decamped in 1982 to Europe, ending up in Rome, where she in turn gave Jean-Michel’s painting to the artist Sandro Chia as a present. She thought she could always get another one.

Danny co-stars with the then-unknown (and homeless) Jean-Michel in Downtown 81, producer and writer Glenn O’Brien’s impressionistic music film. Its narrative arc – two handsome young men wander the city, hang out, go to clubs, smoke, and stay up all night – defines the downtown cultural moment of the time. Shot in 1980–81, the footage vanished into the mist for two decades, its dialogue soundtrack disappearing entirely. The film was found, restored, and officially released in 2001 with Jean-Michel’s voice wild tracked by Saul Williams, adding a special dislocation to a history now inflated into myth.

The year 1980 marked a transition for the New York art world and everyone in it. The 1960s had seen Modernism gorge itself on pop culture, pare itself down to the minimum, and finally dematerialize into an exhausted finale. The 1970s began in a kind of hangover. Everything had been done – what was left to do? One solution was to spread sideways, rhizomatically, rather than progressing ever upward or forward. New York City had barely skirted bankruptcy in 1975, with entire neighborhoods – notably the South Bronx and the Lower East Side – abandoned by landlords and the government. Light manufacturing had departed SoHo and by the 1980s, the area became the art scene’s new wellspring. Its 19th-century cast iron buildings contributed to the new aesthetic thanks to sprawling loft spaces. Jean-Michel adopted a model of art-making that used the detritus of abandoned slum lives rather than industrial castoffs.

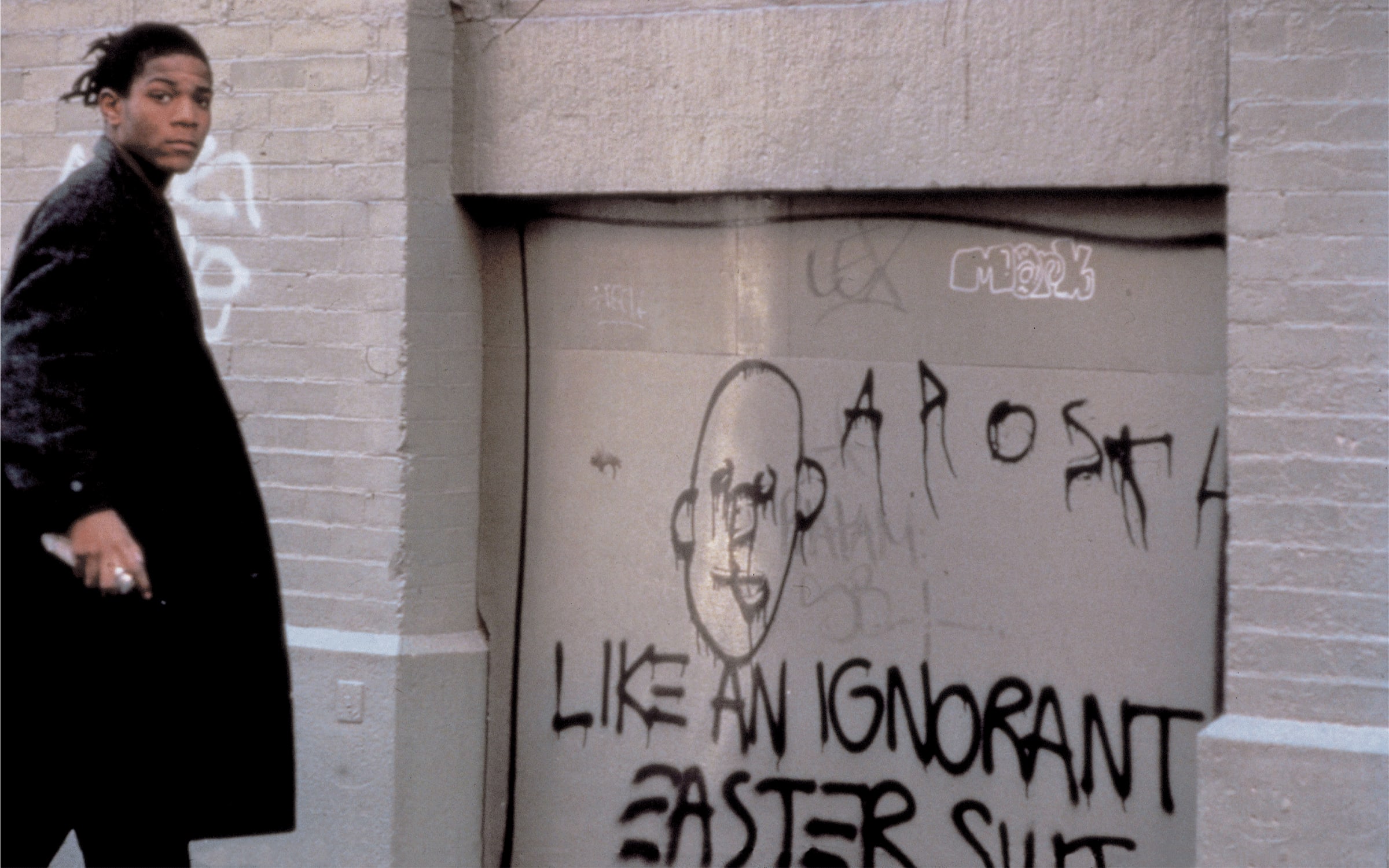

He started with street art. Generations of graffiti artists had already taken to painting subway trains – city officials hated it, artists loved it – but with the exception of isolated exhibitions such as the 1975 ‘United Graffiti Artists’ show at Artists Space, graffiti wouldn’t begin penetrating the art market in earnest until Fun Gallery opened several years later. The art world appropriated the term ‘Graffiti art’ for the public interventions of Jean-Michel and Keith Haring, which only remotely resembled the swashbuckling spray-painted tags that had been perfected by kids from the boroughs.

Basquiat’s briefly ubiquitous graffiti tag – ‘SAMO’, in all caps, a riff on ‘same old’ – was sprayed in black on the subway system’s concrete walls and above ground on billboards and plywood boarding in the late 1970s in collaboration with Al Diaz (who carries on the legend today, documenting his work on Instagram). The graffiti was stylized block letters – his ‘E’ was three horizontal lines – and marked with the copyright symbol, an emoji avant la lettre. His short messages cynically mocked the official art scene: ‘SAMO AS A NEO ART FORM’, ‘SAMO AS AN END TO BOOSH-WAH’, and ‘SAMO FOR THE PEA BRAIN SECT’. My wife remembers a more humorous slogan: ‘SAMO PRAY FOR SOUP BUILD A FORT SET IT ON FIRE’.

Despite the satire, Jean-Michel had ambitions to become part of the above-ground art business. In June 1980, he took part in the seminal, artist-organized ‘The Times Square Show’, notably writing ‘FREE SEX’ above the doorway, which was later painted over to avoid trouble in the still-seedy Times Square district. More dramatically, in a punk fashion show featuring artists dressed in thrift shop gear, Jean-Michel stood by with a house painter’s brush and bucket, slapping paint on the models as they went by.

But by February 1981 he’d quickly morphed from street artist to establishment painter, showing at P.S. 1’s ‘New York/New Wave’ exhibition. Black culture in all its forms was Jean-Michel’s central subject, and he can be credited as a harbinger of the Black presence in art that is only now being fully acknowledged. The artist Stephen Torton, Jean-Michel’s studio assistant, describes an almost delirious, mostly nonverbal work method, characterized by abrupt shifts across the canvas and feverish free association, painting on found objects and home-stretched canvases. ‘It was rata-tat-tat,’ says Torton. The art looked immediate and almost easy. In terms of prolific production, Basquiat was a budding Warhol, but with a human touch.

In 1988, Jean-Michel died of an accidental heroin overdose at age 27. He’d created more than 600 paintings and 1,500 drawings; an inspirational tale with a cautionary conclusion. Isn’t that the stuff of classic tragedy? Such talent, such ambition, such luck. In advance of his first major gallery show, at Annina Nosei in SoHo in May 1981, the air was abuzz with anticipation for this kid and his big brash paintings. We could feel it. We thought we had ‘good antennae’, trained to pick up what was new and important. The next year, in summer 1982, Jean-Michel, just 21, went to Italy on the invitation of gallery owner Emilio Mazzoli to produce new works for a solo exhibition. Working feverishly and intuitively as always, Basquiat painted eight canvases. The exhibition never happened, but these works, now called the Modena Paintings, are on view at Fondation Beyeler, together for the first time.

I realize now we were sensing only a rapidly approaching tsunami of fame and fortune, a flood that hasn’t let up for a minute, not even after, especially not after, the artist himself was swept away.

Jean-Michel Basquiat

‘The Modena Paintings’

Fondation Beyeler, Basel

From June 11 to August 27, 2023

Walter Robinson is an artist and writer based in New York. He cofounded Printed Matter, and with the late critic Edit DeAk edited Art-Rite magazine from 1973 to 1978. He was the editor of artnet.com magazine from 1996 to 2012. As a painter, he is represented by Air de Paris in Paris.

Leave a Reply