A new show at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami explores the layered work of the American artist

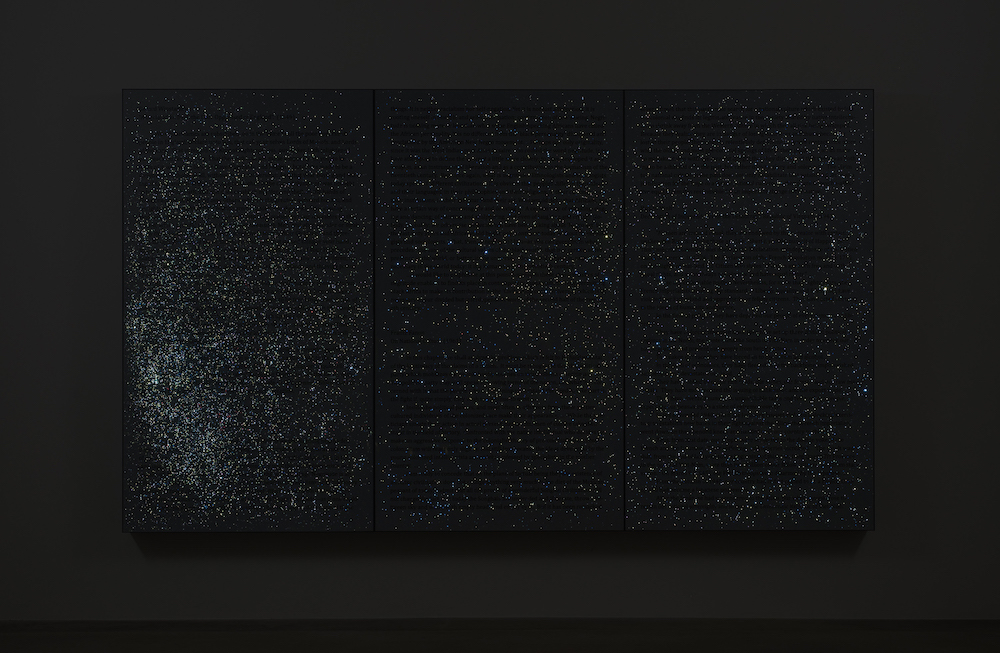

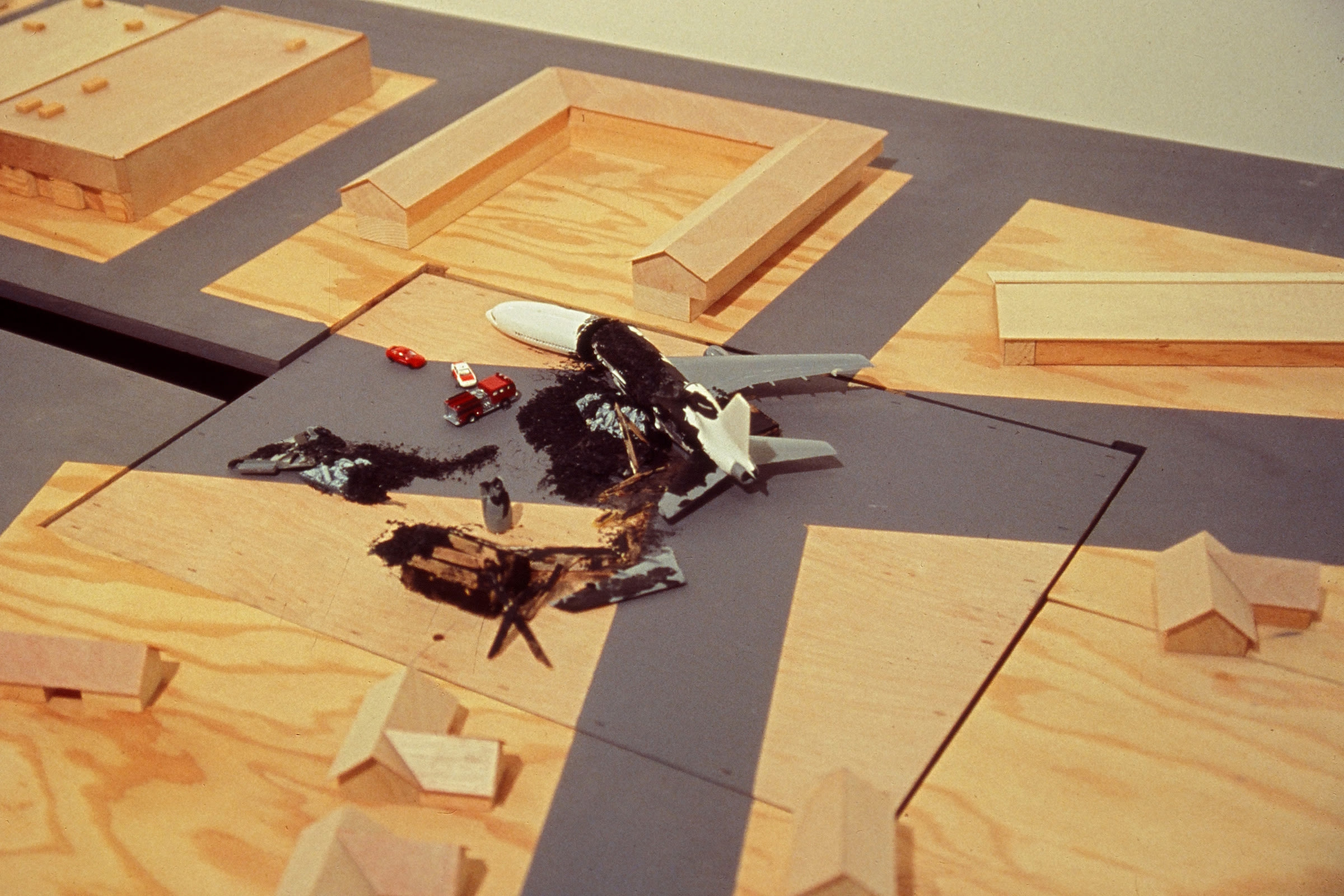

Charles Gaines is the subject of a show that opens at the Institute of Contemporary Art, Miami during Art Basel Miami Beach this year. The survey, ‘Charles Gaines: 1992-2023’, focuses on the latter half of the artist’s career and brings together, for the first time, more than 65 works from 1992 to the present day. Among these are two monumental works recreated by Gaines himself – Falling Rock (2000–2023), a sculpture in which a 30-kilogram chunk of granite drops in a randomized and sudden fashion, and Greenhouse (2003–2023), a massive 3.66-by-4.88-meter sculptural enclosure wherein climate change data is used to obfuscate the trees within, a work not seen in 20 years.

Gean Moreno, the show’s curator and ICA Miami’s director of the Knight Foundation Art + Research Center, says the decision to focus on this later period of Gaines’s output emerged from a desire to showcase work that aligns with today’s demand for political engagement.

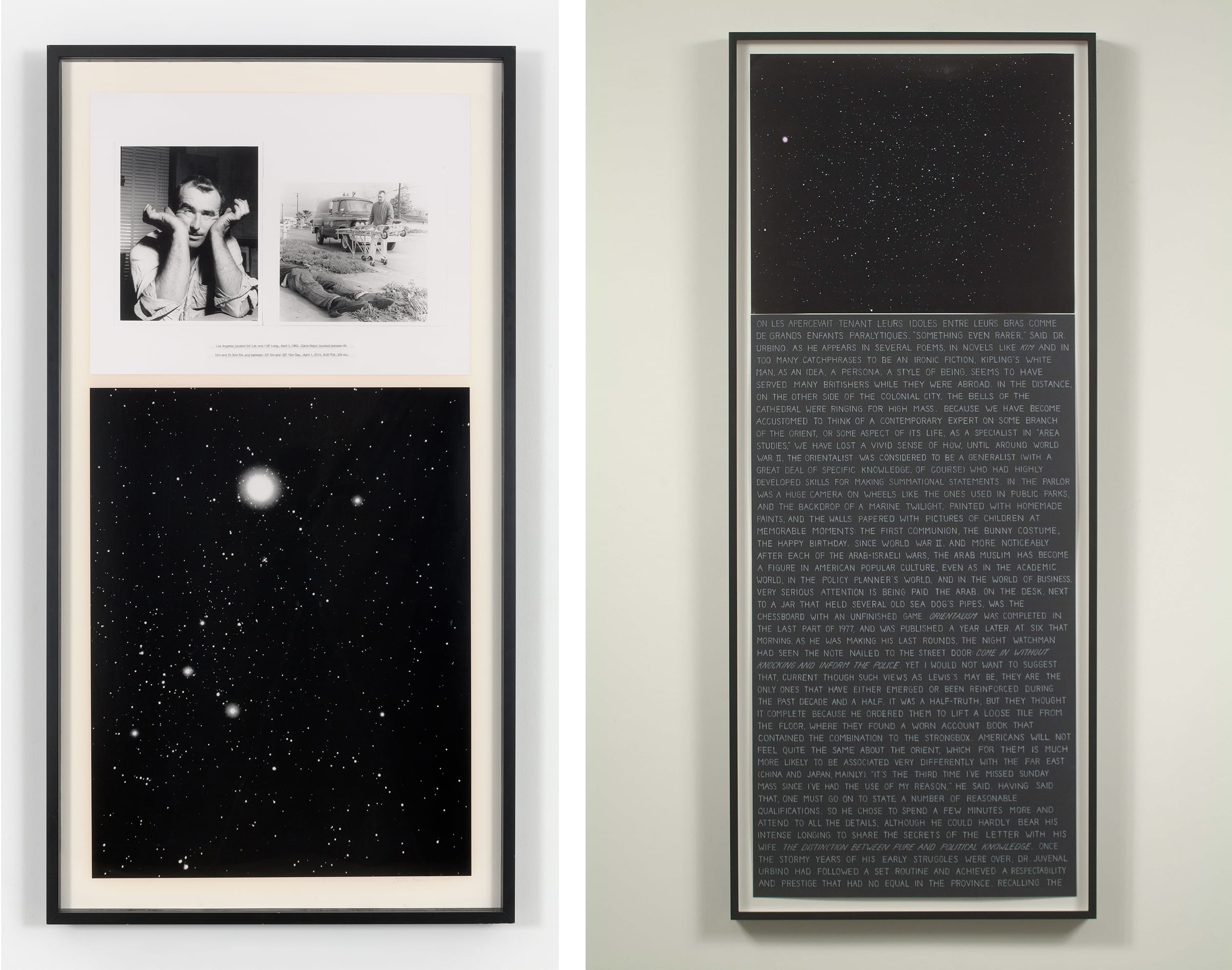

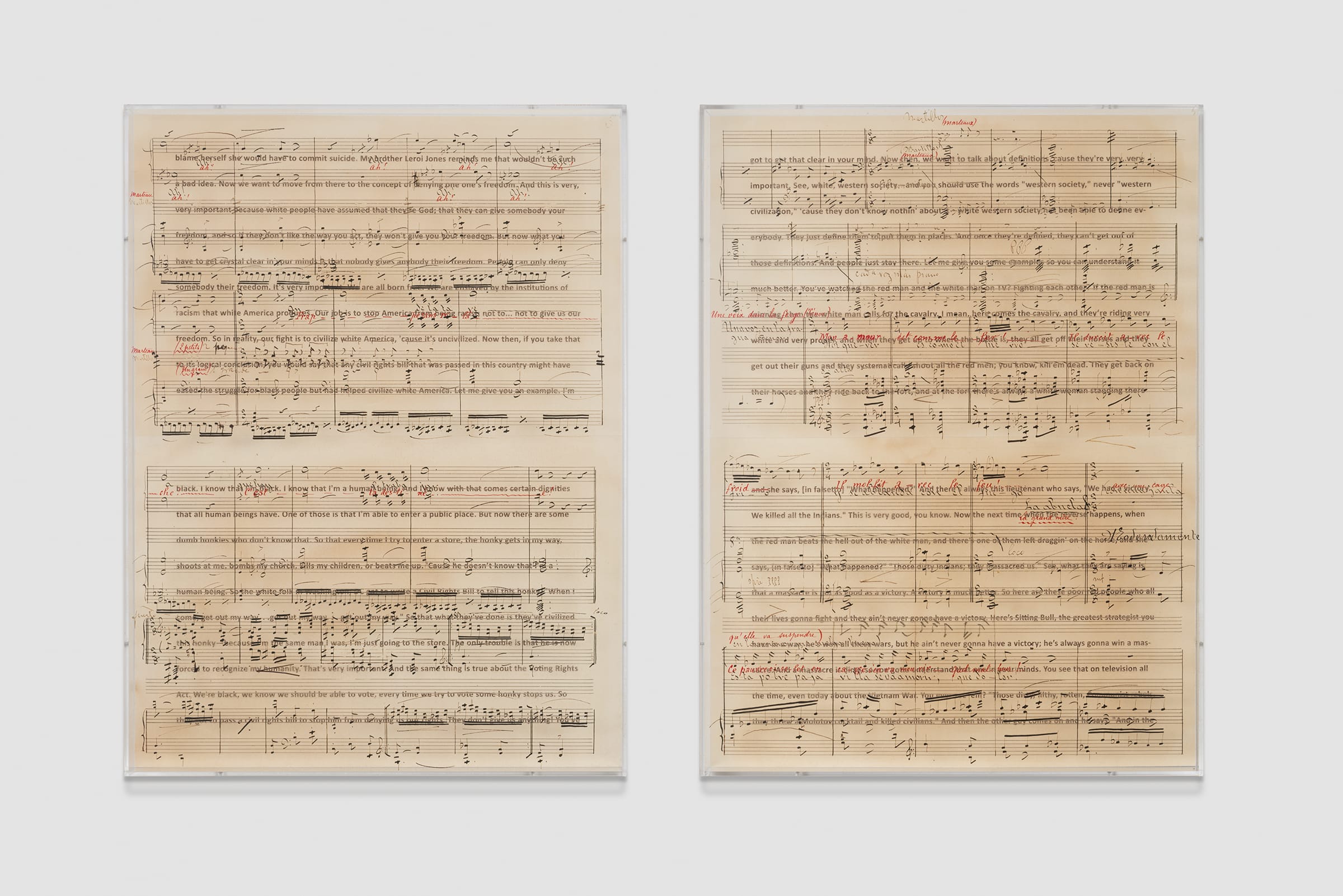

Before the 1990s, Gaines based his artwork on mathematics and photographs. However, ‘in the early 90s, he starts using things like Frantz Fanon’s writings or Kafka’s or the Black Panthers’ manifesto,’ works that become abstracted but at least begin in the recognizable world. ‘It’s drawing from the social field rather than formal experiments,’ Moreno says.

Leave a Reply