A major exhibition at Kettle’s Yard highlights the legacy of a Chinese-born artist whose distinctive artistic journey left an indelible mark on art in postwar Britain

‘The fact that Li Yuan-chia has been missed by the art establishments of so many countries suggests that they have no instruments fine enough to detect a journey such as his,’ wrote critic and curator Guy Brett in 2000. With Li’s inclusion in Tate Liverpool’s ‘Radical Landscapes’ and Whitechapel Gallery’s ‘A Century of the Artist’s Studio’ in 2022 – and a significant focus on his legacy now on view at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge, England – this is set to change.

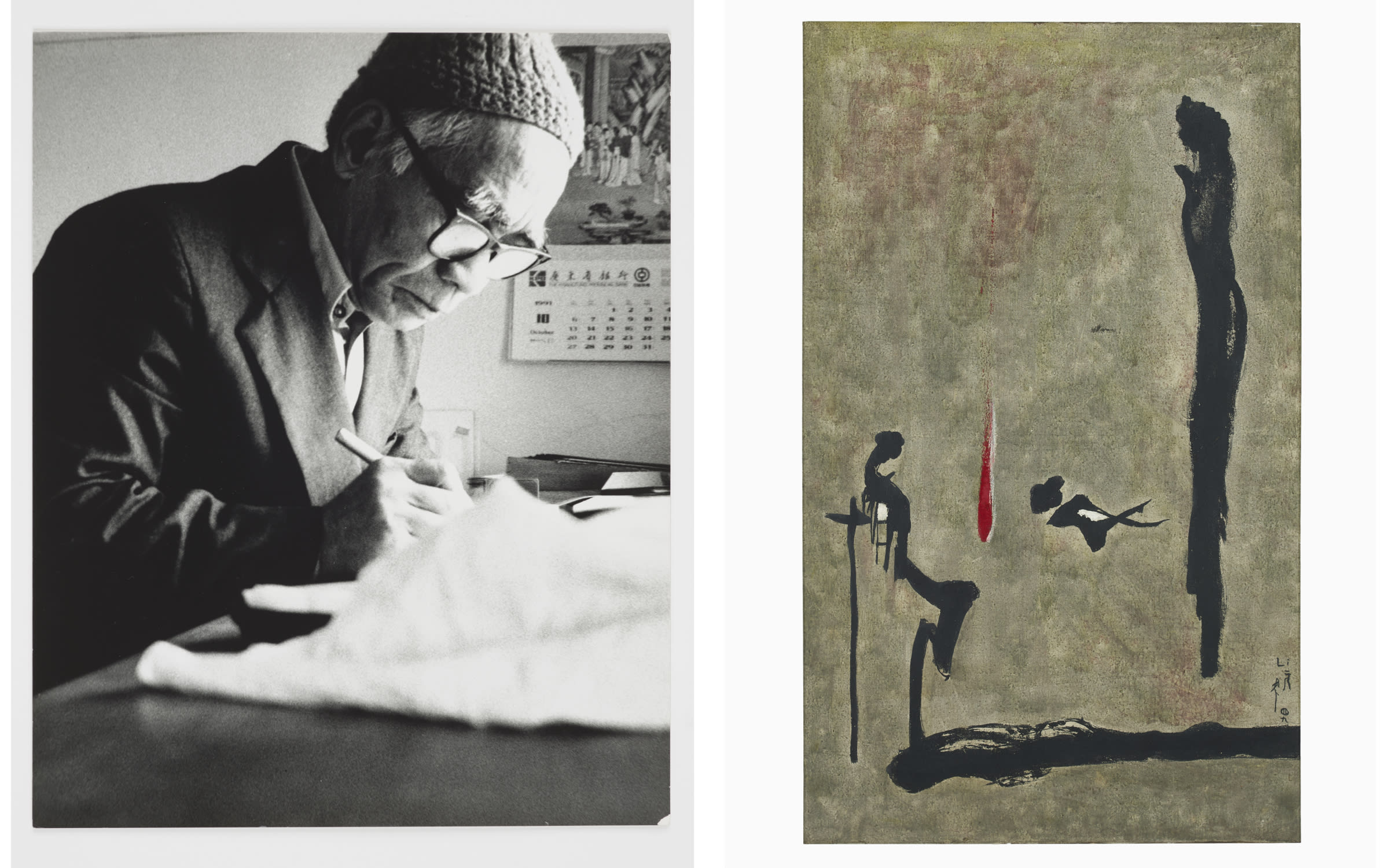

Born in 1929 in Guangxi, China, Li was an artist, poet, designer-maker, curator, organizer, publisher, and museum-founder, whose practice spanned ink painting, gestural abstraction, wood reliefs, kinetic sculptures, immersive environments, photography, and what would now be called socially engaged art. Associated with several Modernist artist groups in Taiwan, Italy, and the UK, his interests were informed by the zigzagged trajectories of a distinctive artistic journey that, as Brett noted, not only crossed ‘geographical and cultural boundaries but also those of the concepts and practices of art.’

Li moved to Taiwan in 1949 because of the Chinese civil war, where he joined the Ton-Fan Group, founded in the late 1950s by artists keen on experimenting with abstraction. In 1962, Li moved to the Italian city of Bologna at the invitation of fellow Ton-Fan artist, Hsiao Chin, who founded the art movement Punto (Point) in Milan in 1961 with artists Antonio Calderara and Azuma Kenjiro. Interested in integrating Buddhist concepts into postwar art, the Punto group positioned the symbol of the point, which Li described as ‘the beginning and end of everything’, as a guiding principle. The point became the initial vehicle for Li’s artistic development in Europe, evolving from a spot of color on early monochromatic paintings into movable magnetized objects that sometimes incorporated photographs and poems, which Li referred to as ‘toys.’ In Double-sided Black and White Magnetic Relief (1969), a steel disc painted white on one side and black on the other is suspended from the ceiling. Li intended for audiences to move the black, white, and red circular, rectangular, and triangle-shaped wooden blocks attached to the disc with magnets.

1966 was a pivotal year in Li’s life. An invitation to show his work at the seminal Signals gallery, founded in 1964 by art critics Guy Brett and Paul Keeler with artists David Medalla, Gustav Metzger, and Marcello Salvadori, brought him to London. Following Signals’ closure in 1966, Li staged three solo exhibitions and participated in three group shows at Lisson Gallery between 1967 and 1970. He showed alongside contemporaries including Lygia Clark, Ian Hamilton Finlay, dom sylvester houédard, Derek Jarman, Mira Schendel, and Takis, who shared avant-garde interests in kinetics, participation, and concrete poetry. Li’s ‘Golden Moon Show’ at Lisson Gallery in 1969, created an immersive environment comprising a working swing and movable sculptures, including Double-sided Black and White Magnetic Relief. The exhibition was timed to coincide with Apollo 11’s mission to the moon and encouraged cosmological readings of Li’s work – an association that was heightened by Li’s infinitely elastic and expansive understanding of the point as both idea and form, which echoed contemporaneous scientific discussions of the big bang theory at a time before it was widely accepted by the scientific community.

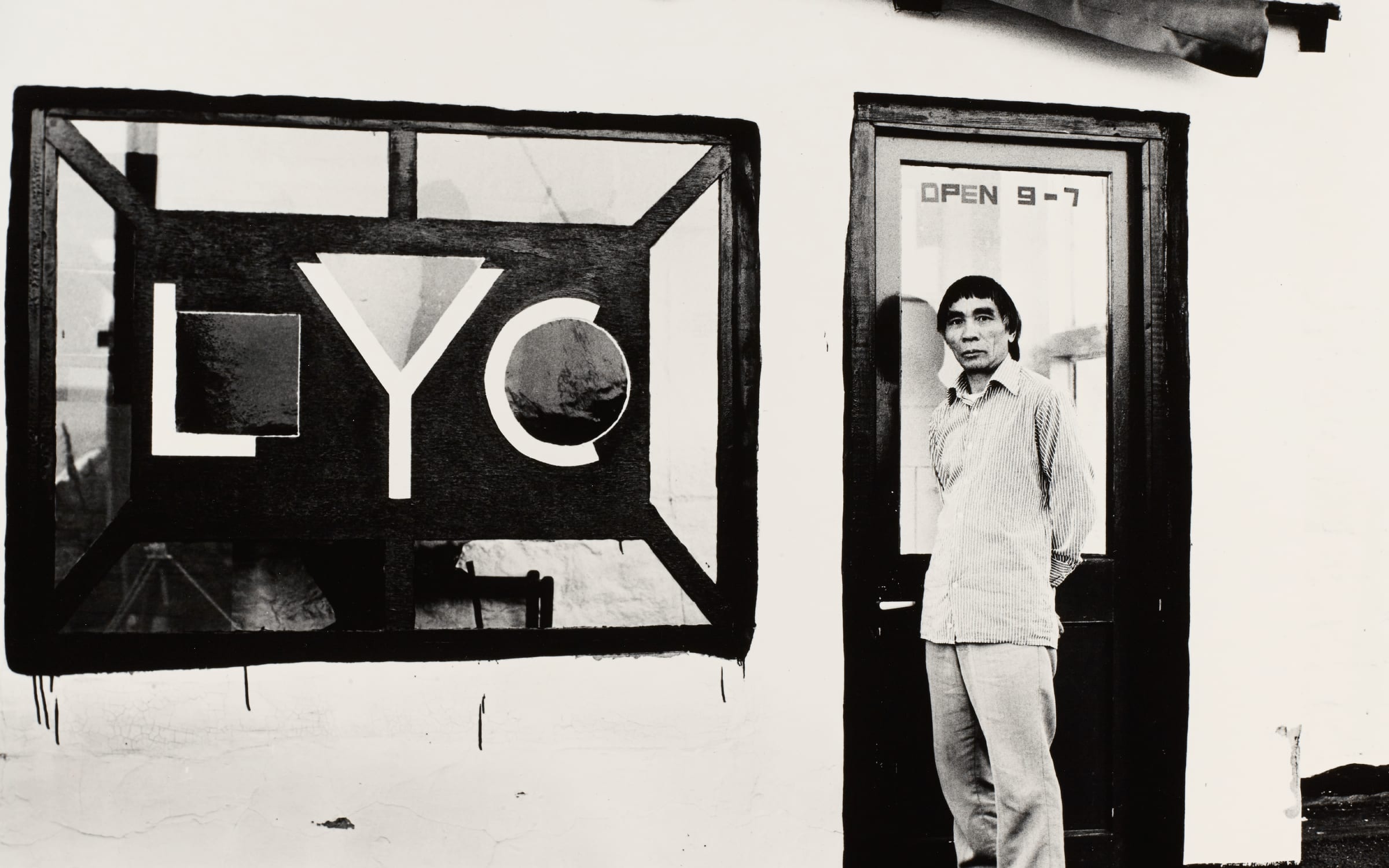

Perhaps more pivotal than Li’s arrival in London, however, was his fateful trip to Cumbria in December 1967, when he visited his friend Nick Sawyer’s family home. Li was so taken with the area that he decided to stay there for the rest of his life. He settled in the Cumbrian village of Banks to develop what is arguably his most important work: the LYC Museum & Art Gallery. Li acquired a site of dilapidated farm buildings from his friend and neighbor, the painter Winifred Nicholson, in 1971, and set about creating a hyper-active space for art. Completing most of the building work himself, the LYC Museum staged Li’s expansive transformation from artist to curator of art and social interactions.

Between 1972 and 1983, the LYC’s eclectic exhibition program showcased works by more than 320 artists and makers. They included leading figures associated with British Modernism such as Ben Nicholson, Barbara Hepworth, and Naum Gabo; local artists Andy Christian and Susie Honour; artists who went on to develop international careers, among them Lygia Clark and Andy Goldsworthy; and pioneering figures like sound artist Delia Derbyshire, Li’s assistant – and briefly partner – at the museum from 1976 to 1977. Besides its galleries, the museum had a children’s art room, library, performance space, printing press, communal kitchen, and garden. It was an open space of possibility and connection, and researchers have only recently begun to explore the networks and practices that the LYC enabled.

Sometimes, it is suggested that Li sacrificed his practice for the LYC. But the museum is increasingly seen as his greatest artistic creation, which extended from his interest in participatory practices. Li showed how the operational activity of running a museum – the openings, performances, programming, publishing activities, and indeed the running of the kitchen – could be considered an artwork in its own right. After it closed to the public in 1983, the grounds became the setting for a series of hand-tinted photographs that Li created featuring everyday objects – scarves, shearing scissors, a chair, a broom, an axe – and his own body.

In 2014, Li was positioned as the ‘father of conceptual and abstract art in Taiwan’ by the Taipei Fine Arts Museum, whose posthumous retrospective of Li’s work took place more than 50 years after he left the country. Yet his contribution to postwar art has remained largely unrecognized in Britain, where he remained until his death in 1994, with just one posthumous retrospective organized in the country by Iniva, curated by Guy Brett and staged at the Camden Arts Centre in London in 2001. But this has been gradually changing. ‘Making New Worlds: Li Yuan-chia & Friends’, which opened at Kettle’s Yard in Cambridge this November, makes the case for Li’s profound place in British art history by placing the LYC in conversation with the history of Kettle’s Yard, founded in 1966 in the house of curators, collectors and self-defined ‘friends of artists’ Jim and Helen Edes. Blurring the boundaries between home, art making, display, and hospitality, both sites were crucial nodes in the circulation of creative energies and practices in postwar Britain, with a notable overlap of artists who showed at each location.

But this connection between Kettle’s Yard and the LYC also highlights the differential status of these spaces within art history. The former has evolved into a much-treasured cultural institution in Britain while the latter stands in ruins. With that in mind, ‘Making New Worlds’ not only places Li’s works in dialogue with artists he exhibited in Cumbria, but also features contemporary artists who have been inspired by Li’s legacy, like Grace Ndiritu, Aaron Tan and Charwei Tsai. Their work is a testament to how the energy of Li’s practice has not been lost so much as transformed through time.

‘Making New Worlds: Li Yuan-chia & Friends’ is on view at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge from November 11 to February 18, 2024.

Hammad Nasar is a curator, writer, and Senior Research Fellow at the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Along with Sarah Victoria Turner and Amy Tobin, he curated ‘Making New Worlds: Li Yuan-chia & Friends’ at Kettle’s Yard.

Published courtesy of Art Basel.

Leave a Reply