Collectors are increasingly using loans to buy; Art Basel examines the mechanisms

Andy Warhol famously quipped that ‘being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art.’ But an artwork is itself an investment, and few collectors would ignore that their purchases can appreciate in value. Unlike stocks and other fungible assets, however, unique artworks cannot simply be traded on a whim or converted easily to cash – which is where the burgeoning category of art lending comes in.

Sayuri Ganepola, Global Managing Director of Christie’s Art Finance, says, ‘There’s always a bit of friction within the art market when it comes to buying and selling – the timing of when you’re freeing up liquidity from other places in your portfolio versus the timing of the sale.’ Art loans, she says, can help ‘solve the mismatch.’

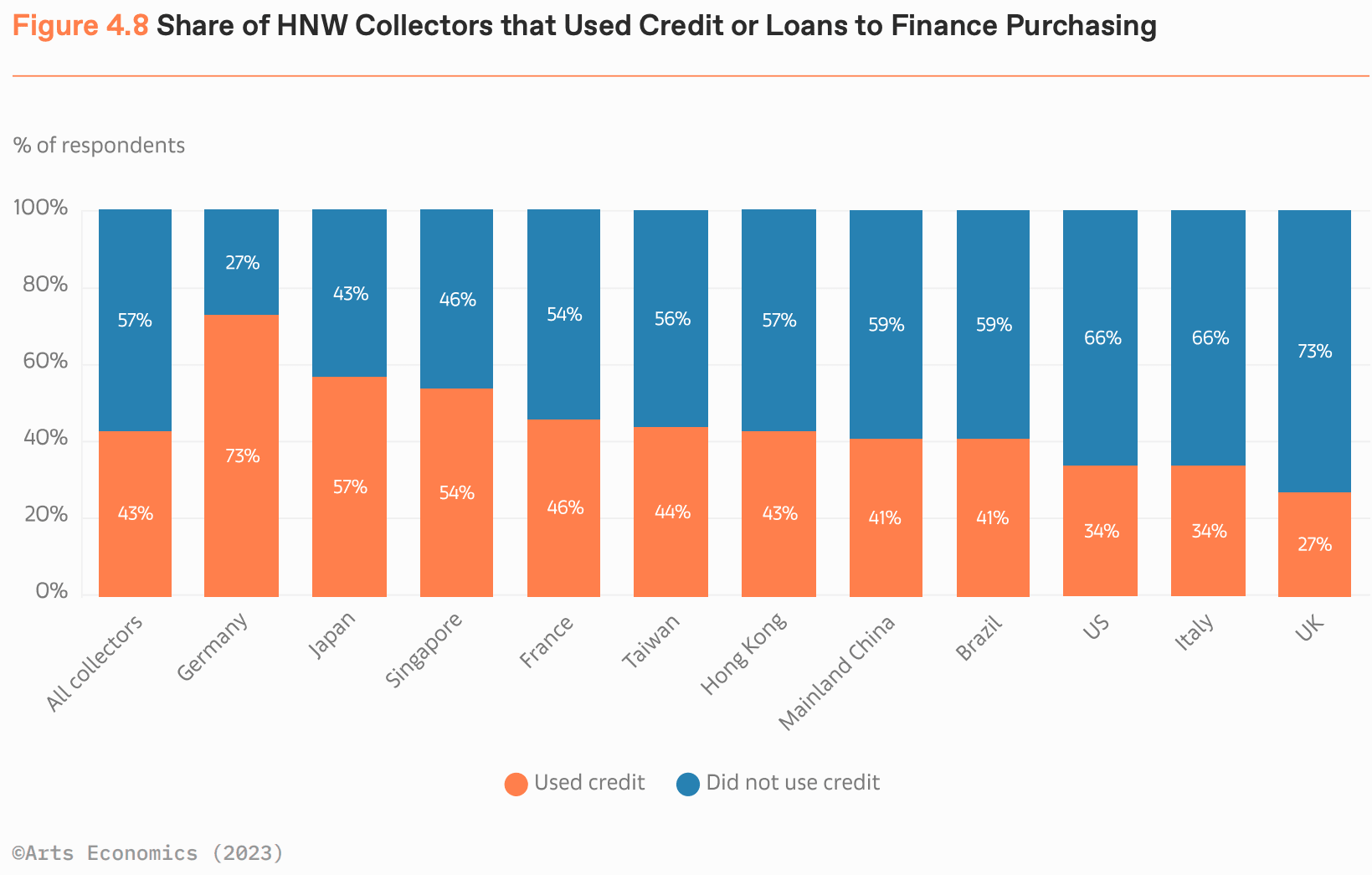

Increasingly, collectors are exercising this option. In the Art Basel and UBS Survey of Global Collecting 2023, the report’s author Dr. Clare McAndrew found that 43% of high-net-worth (HNW) collectors reported having used credit or a loan to purchase works of art or objects for their collections, with 30% relying on it in the past 2 years. Credit usage was highest among collectors in Germany and Japan versus the bigger markets of the UK and US.

Still, the share of UK and US collectors availing themselves of financing for art purchases appears to be rising; McAndrew’s survey pegged usage among US HNW collectors at 34%, versus 21% in 2022 and 2023, and against a previous study from 2018 which charted them at 11%.

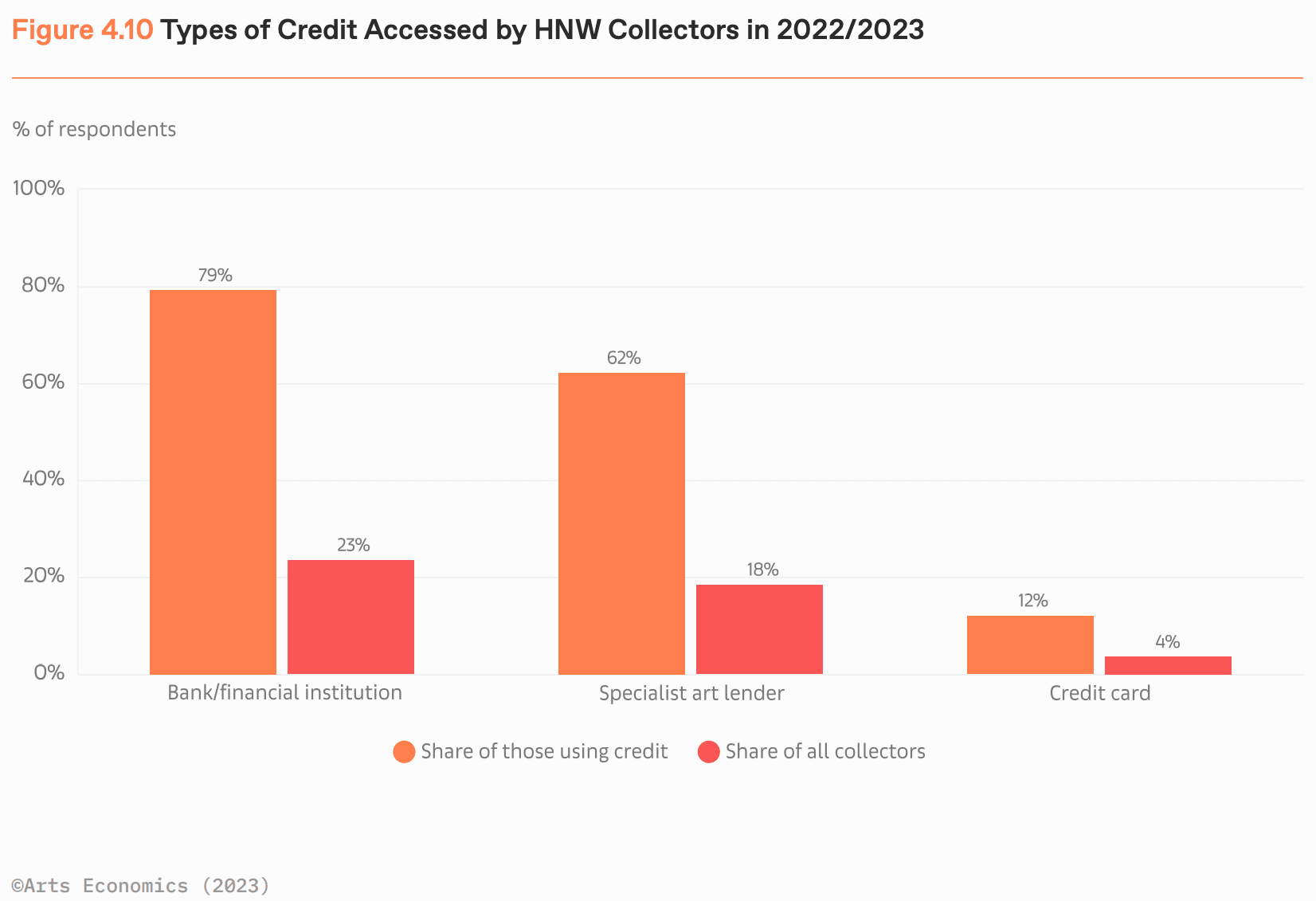

As McAndrew’s survey demonstrates, collectors have options when looking to buy art on credit. They may obtain a loan from an institution, such as a bank (79% of credit users in the survey); they may work with a specialized art lender (62% of credit users in the survey), often employing their existing collection as collateral to secure a loan; or use a credit card (12% of credit users in the survey, and usually in concert with another type of loan).

A new class of consumer credit providers, such as Art Money, Borro, and Arternal’s partnership with Affirm, is now targeting the luxury world. A key distinction between institutional and specialized lenders, says Scott Milleisen, Global Head of Lending at Sotheby’s, is that ‘a bank will evaluate and underwrite the borrower, whereas we underwrite the collateral.’

Given the understandable discretion surrounding the industry, it is difficult to quantify the overall art lending market, but it is sizable. Sotheby’s, which has made lending the linchpin of its Financial Services division since 1988, holds a loan book that, per Milleisen, swelled 30% in 2023, to ‘solidly above’ USD 1 billion. Specialist lender Athena Art Finance, which in 2019 was acquired by the investment firm Yieldstreet, has granted more than USD 720 million in loans since debuting in 2015. Christie’s declined to provide numbers, but cited ‘exponential growth.’

Historically, financing has not been the norm in the art trade. In the past few decades, banks including UBS, Citibank, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, Emigrant, and others have established dedicated fine art finance and advisory teams. Auction houses, too, have long offered their highest-value clients a path to settle transactions and advance funds. But in the past 15 to 20 years, new independent boutique lenders have emerged to serve the art world. A loan can unlock cash for time-sensitive acquisitions, where collectors need to move quickly on an offer, and allow them to take advantage of steep appreciations in value without having to sell.

‘You can finance everything now, even a microwave. But art was never in that field. Art was always something you put apart,’ says Thomas González. The Berlin-based art historian shifted his focus from art sales to finance in 2009, when he realized the need for an industry-specific conduit. ‘Banks didn’t trust the galleries; galleries didn’t trust the banks… I do translation in both directions,’ he explains. González grants non-recourse loans of EUR 25,000 to EUR 100 million, with interest rates starting at 9.5%, with his funding partner, the German private bank IBB. ‘Every serious collector is buying and selling all the time.’

Among the new-guard entrants focused on consumer credit is Art Money, founded in 2015 by the Australian entrepreneur Paul Becker to deploy fintech solutions to facilitate interest-free art purchases in the USD 1,000 to USD 100,000 range. ‘You wouldn’t pay up front for a house. Most people don’t pay up front for a car. We’re just normalizing this in the artworld,’ he says. ‘One of our clients says, “The best art often comes at inconvenient moments.” That’s so true, financially. And so we just smooth all that out, as every other industry in the world has done.’

In the case of Art Money, the process starts with an on-demand evaluation that can be completed from one’s mobile phone from the aisle of an art fair. Once approved, it is up to the buyer to let the gallerist know they would like to pay with Art Money, and the gallery to be or sign on as a partner to accept payment (there are currently nearly 2,000 partners around the world, including many Art Basel galleries, ‘and signing more every day,’ says Becker). ‘It’s a win-win business model where we pay the seller upfront, the client pays over time, and someone pays a 10% commission to do that, whether it’s the gallery side or the client side,’explains Becker. The company received an investment from Christie’s Ventures division last year.

Dionne Harmon, an Emmy-winning producer based in Los Angeles who has been collecting since 2015, was referred to Art Money by the artist Knowledge Bennett. ‘I had been eyeing one of his large-scale pieces from the “Obama Cowboy” series, Five is Power (2017). At that point, it was the most expensive piece of art that I had ever considered purchasing, at USD 50,000,’ she says. ‘I told Knowledge that I loved it but I was nervous about spending that much money upfront.’ He told her about Art Money and, says Harmon, ‘I was all in.’ Since then, Harmon has acquired six more pieces using Art Money.

When the goal is something other than an art purchase on the spot, collectors can turn to art-specific lenders to gain liquidity against their holdings without having to sell them. In general, lenders will be looking for blue-chip artists with established secondary markets, and may require a minimum valuation. Auction houses can consider a collector’s holdings across multiple categories, such as jewelry or wine, and advance against a consignment. Loan-to-value ratios are usually between 40% and 60%, interest rates may be fixed or floating, and the repayment time frame might range from 6 months to a year with the option of renewal. In most cases, the collector will arrange for the artwork’s physical transfer.

Collectors seeking a sizable capital infusion must be comfortable with a forensic-level probe. ‘Clients who are considering loans should expect to provide evidence of their full ownership and title to the artwork,’ says Rebecca Fine, Managing Director of Athena Art Finance. ‘That consists not only of an invoice, but also of proof of payment of the purchase price’ – occasionally an obstacle when the acquisition was long ago. A borrower will need to furnish documents such as a condition report, a third-party appraisal, and a provenance and/or exhibition history. In arrangements where the collector maintains possession, the lender may scrutinize insurance policies and assess physical security risks.

Those in the field expect lending against or to buy art will become more common as the pool of collectors grows younger and more diverse. Christie’s Ganepola observes ‘a very strong appetite’ in her US and Asia markets. ‘Culturally, the acceptance around taking on debt is changing,’ she says, and for nascent art buyers, ‘we are looking at ways where they can use leverage to help build their collections, so the whole thing fits neatly together.’

As financing has for other assets before it, the expansion of art lending stands to democratize participation in the artworld. ‘Art Money has allowed me to grow my collection at a much faster rate,’ says Harmon. ‘It has also made collecting high-value art much more accessible for me.’ Including, it should be noted, a prized Warhol.

– Sarah P. Hanson is a New York–based writer specializing in contemporary art and the art market. Published courtesy of Art Basel.

Leave a Reply