He will unveil a monumental new tapestry at Art Basel Hong Kong

Sometimes it takes a village to make an artwork – or rather, a group of highly skilled artisans from your hometown. This is the case for Tsherin Sherpa’s installation Stairways to Heaven (2024), soon to be unveiled in the Encounters sector at Art Basel in Hong Kong, dedicated to large-scale artworks. Depicting a partially obscured dragon (a fitting motif for this lunar year), the 10-meter-long tapestry was woven by hand by craftspeople in Kathmandu, Nepal’s capital.

Sherpa was born in Kathmandu in 1968. As a teen, he trained under his father, Master Urgen Dorje, in thangka painting, a traditional Tibetan art form that depicts Buddhist themes on cloth or silk. In the late 1980s, Sherpa moved to Taiwan to study computer science and Mandarin. A decade later in 1998, he ventured further onwards to California, where he taught traditional art at Tibetan Buddhist centers across the Sunshine State.

Over the years, as Sherpa was inundated by California’s hyper-saturated, turn-of-the-millennium commercial culture, his paintings began to take a turn; a change which he describes as his shift from making ‘traditional art’ to ‘contemporary art,’ in an interview with Art Basel.

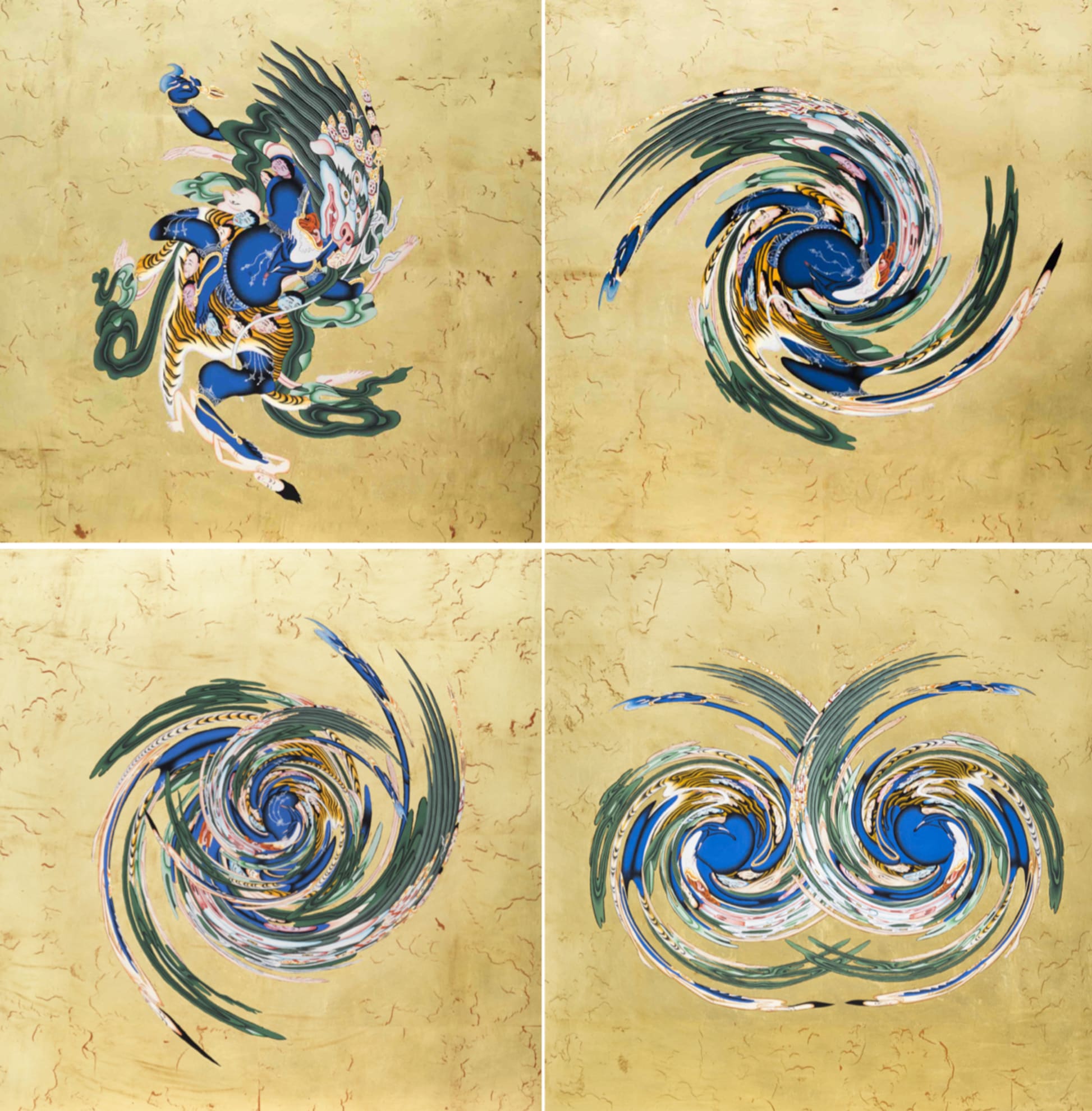

The latter practice borrows from the former: Using the motifs, colors, and symbolism of traditional Tibetan art, Sherpa began exploring contemporary, secular subjects. In paintings such as Things That Pop in My Head (2009) and Conqueror (Gangnam Style) (2015), he remixes, reconfigures, and repurposes spiritual iconography with imagery from pop culture including brand logos, consumer products, and modern apparel.

Though bright and colorful, the works address ideas of displacement, loss, and ultimately, triumph. In ‘Spirits’, perhaps his best-known series, Sherpa imagines Buddhist deities forced to leave their homeland for a hyper-commercialized modern world. How, like so many displaced Tibetans, would they adapt to an unfamiliar place?

With this shift in subject matter, the art world took quick notice of Sherpa’s work, and in 2010, he was awarded the Himalayan Fellowship by New York’s Rubin Museum of Art – a museum specialized in Asian creative practices, with a focus on Tibetan art. Since then, Sherpa’s work has been exhibited at the Asia Society in New York, the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, and several international biennials.

As Sherpa found professional success, he was compelled to champion other Himalayan artisans through collaborations. In 2022, when he was selected to represent Nepal for the country’s debut at the Venice Biennale, he worked with multidisciplinary craftspeople to create installations that challenged reductive, fetishized notions of Nepal as a spiritual Shangri-la.

While he has collaborated with artisans working in many different disciplines, rug making has been of particular interest to Sherpa since he returned home to Kathmandu after the region was hit by a devastating earthquake in 2015. In the disaster’s aftermath, Sherpa noticed that rugs played an important role in Nepalis’ daily lives. As Sherpa describes, with many displaced from their homes due to the structural risks posed by aftershocks, people pitched tents outdoors and lived and cooked among one another. At the heart of these makeshift communities, handmade rugs laid upon the ground were vital spaces for gathering and socializing.

Rug making is deeply ingrained in Himalayan culture, representing the region’s artistic heritage and its connection to spiritual beliefs and natural landscapes. However, with an increase in tourism and commercial interest, the craft became overly commodified in recent years. Sherpa laments that what used to be a cherished tradition, passed down through generations, became something more akin to a souvenir industry.

Motivated to change the status quo, Sherpa decided to collaborate with artisans to celebrate their skill and reestablish rug making as an integral Himalayan art form. Many skilled hands went into the multiple intricate steps including yarn-making (most often done by women), weaving, washing, detailing, and cutting. On view at the fair, Stairways to Heaven (2024), depicts a dragon seemingly disappearing and then triumphantly reappearing throughout the silk, cotton, and wool fibers. While Sherpa often leaves his works open to interpretation, preferring to let the viewer make their own conclusions about their meanings, he hints that the dragon’s oscillating presence suggests how at one point, traditional Himalayan rug making was disappearing into itself. It is now back, at least at Art Basel Hong Kong.

Tsherin Sherpa is represented by Rossi & Rossi (Hong Kong) and Almine Rech (Paris, Brussels, London, New York, Shanghai).

Elliat Albrecht is a writer and editor based in Canada. She holds a BFA in Critical and Cultural Practices from Emily Carr University of Art + Design and an MA in Literary and Cultural Studies from the University of Hong Kong. Published courtesy of Art Basel.

Leave a Reply