A dynamic new “consumer class” emerging from Africa is attracting international attention. With the prospect of rising incomes and a young population, international consulting firms see the continent as the next frontier for consumer goods. Global entrepreneurs even warn of the increasing savviness of African buyers.

But the influence of African consumers on global markets is far from a new thing. In the 1800s, the continent’s consumer demand called the tune for European factories.

We’re a team of economic and social historians, anthropologists, and African studies specialists. Our research project investigates the roots of these dynamics.

Focusing on the African demand for goods like arms, beads and cloth, our research calls into question the Eurocentric idea that Africa was just a supplier of cheap labour and raw materials before the “Scramble for Africa” by colonial powers.

Instead, in the 1800s, the continent was a key driver of industrial production, compelling manufacturers to tailor their goods to African preferences.

This challenges the conventional view of globalisation as a flow of goods and ideas from dominant economies to so-called peripheral regions. In fact globalisation has always been a connected process – one in which African consumers, though often overlooked, played a decisive role in shaping global markets.

Arms

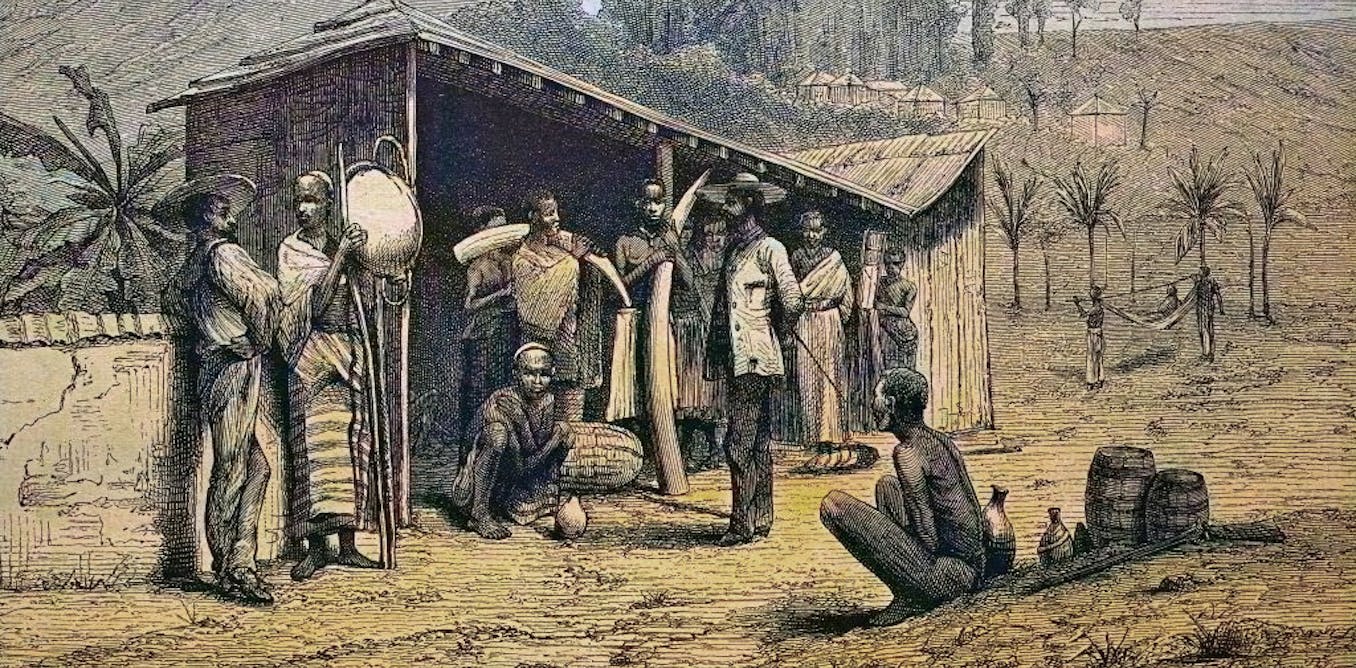

Analysis of the arms trade takes us to the Congo River estuary in the late precolonial era. Before the late 1800s and colonialism, this region was free of direct European political control.

The illegal slave trade lasted at least until the mid-1850s, when the export of legitimate goods finally began to gather momentum. From roughly the 1850s, one of the products most consistently favoured by consumers in the Congo estuary was the so-called “trade gun”.

These rugged, muzzle-loading muskets were deemed outdated by European manufacturers and traders. In the Congo estuary these firearms remained in high demand.

Trade guns could be flintlocks (using a flint to ignite gunpowder) or percussion guns (using a small, explosive cap to ignite it). Flintlocks were more popular because flintstones were more readily available in Africa.

Moreover, smoothbore muzzle-loaders, commonly made from “soft” wrought iron rather than “hard” steel, were not only cheaper but also a more accessible technology than rifles for African consumers. Although flintlocks were sometimes not effective for big-game hunting, they had substantial military value.

Understanding the role of these weapons in African history, however, requires looking beyond just their function. Imported firearms were also commonly given symbolic meanings shaped by local norms and power structures.

For example, among Kikongo speakers in the lower Congo, gunfire was used as a sign of rejoicing during celebrations and funerals. Noise was believed to drive away bad spirits and aid passage into the spirit world.

Although the gun trade in the lower Congo is not always easy to quantify, it is documented, for example, that the Nieuwe Afrikaansche Handels Vennootschap imported an annual average of about 24,000 guns between 1884 and 1888. The majority of these were discarded French percussion guns that had been modified into flintlocks in Liège.

The development of the arms trade in the lower Congo also mirrors broader changes within the European firearms industry. African consumer demand was not just driven by European industrial output, but was rather an active force that shaped and sustained global economic integration throughout the 1800s.

Beads

Venetian glass bead producers were well aware that their specialised industry depended on demand from Africa and Asia. It is almost impossible to find out exactly how many glass beads were poured into the African continent in the 19th century. Glass beads went through many different hands (in many different ports) before they reached the shores of Africa, and the available information on Venetian production is not consistent.

Historians have shown that, during the 1800s, beads produced in Venice were a key commodity exchanged for ivory along the east African caravan routes connecting the Swahili coast to the Great Lakes. These routes were established by Arab traders and Nyamwezi traders (from today’s Tanzania) on expeditions financed by Gujarati merchants from India.

As demand for ivory grew in European and American markets, these traders began penetrating deeper into the continent to discover new sources of elephant tusks and rhino horns. They established new market centres in the process.

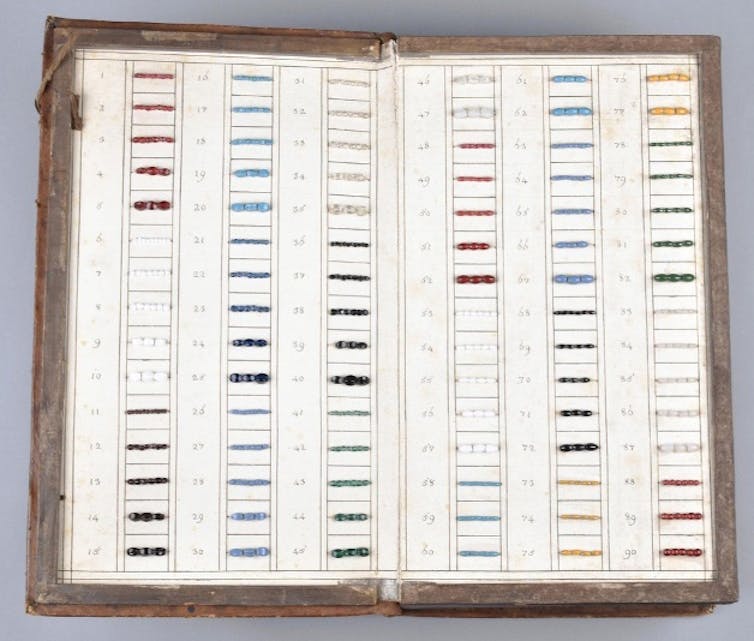

© British Museum, CC BY-NC-SA

Glass beads were portable and relatively cheap. This made them especially suitable as a form of money in everyday transactions. Beads had a major importance in securing food for caravan porters. Bringing the wrong type of beads could spell disaster for an expedition. This required an updated knowledge of the kinds of beads that were more in demand along specific routes.

Through the caravan leaders, information was gathered by European agents in major commercial hubs such as Zanzibar. This was mailed or telegraphed to their companies’ headquarters, allowing producers to respond to demand as promptly as possible.

Today, sample cards displaying the most requested kinds of glass beads, preserved in European and American museums, are the most tangible product of this information chain.

Cloth

African demand also influenced technological innovation. On the coast of east Africa and in Sudan, people eagerly imported millions of yards of American unbleached cotton cloth. This helped build the fortunes of US industries – so much so that “merikani” (from “American”) became a general term for this product – and, later, of Indian manufacturers.

Its spread, however, was limited by transport costs. Ethiopian markets were supplied mainly by local production, with a robust tradition of cotton spinning and weaving. The cloth was distinctively white and soft – praised by travellers as comparable to the finest European textiles. In Ethiopia, the only clear technological advantage enjoyed by western producers was dyes, especially after the introduction of synthetic colours in the 1870s.

Ethiopian weavers eagerly sought coloured yarn from Europe and India to pair with their own white cloth. This demand stimulated the spread of new dying technology abroad. The situation changed significantly after the unification of Ethiopia under Menelik II, whose reign brought stability and infrastructure development.

Coarse, unbleached cotton became widely available even in the interior, offering a cheap and easily washable option for ordinary people: 12 million square yards from the US were imported in 1905-1906 alone. Meanwhile, Ethiopian elites continued to favour local cotton but complemented it with imported accessories like felt hats and umbrellas. Coloured cloth, once a luxury, became a popular consumer good.

The big picture

The story of how arms, glass beads and cloth were commercialised in Africa and how production and distribution had to adapt to the continent’s needs provides a more nuanced picture of how global trade as we know it took shape.

Our research emphasises that globalisation was not ignited in the global north, but depended on consumers located far from the centres of production.

Alessandro De Cola, Univertsity Assistant (Postdoc), Universität Wien; Università di Bologna; Giorgio Tosco, Research Fellow, History Department, Universität Trier, and Mariella Terzoli, Postdoctoral Research Fellow

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply