Many nonprofits, including top universities and museums are confronting serious ethical dilemmas regarding accepting tainted money.

The MIT Media Lab, an interdisciplinary research lab, has been widely criticized for taking money from late billionaire Jeffrey Epstein, who was convicted in 2008 for sexual exploitation of minor girls. Harvard University has now promised to give away Epstein’s unused money to support groups for sexual assault victims.

Similarly, prominent museums such as the Guggenheim, Tate and Britain’s National Portrait Gallery will no longer accept donations from the Sackler family following allegations about its role in marketing practices that pushed opioids on patients who did not need them.

Is taking such money acceptable?

This dilemma is a longstanding one. As a historian of American religion, I’ve examined an episode in the career of a prominent Ohio pastor named Washington Gladden, who led a campaign for the return of a US$100,000 gift from philanthropist John D. Rockefeller way back in 1905.

Then as now, the key issue was whether groups concerned with the public good could justifiably take money from people of questionable morals.

Defending Rockefeller’s gift

Rockefeller’s $100,000 gift – approximately $2.7 million now – went to the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions, an organization that oversaw the overseas missionary activities of the Congregational Church.

Few people in the early 20th century doubted that Rockefeller’s company, Standard Oil, was engaged in questionable practices.

Among other things, Rockefeller had created a system of shell railroad companies. He shifted Standard Oil’s rail freight to his own companies, thereby driving competing railroads out of business and leaving their employees out of work.

Despite knowing his cut-throat methods, many people at the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions board happily accepted Rockefeller’s money.

“Before gifts are received the responsibility is not ours,” declared a subcommittee responsible for evaluating the contribution.

The mission’s position was that provided the money was acquired legally, there were no ethical concerns.

Graham Taylor, a prominent Chicago minister and social reformer agreed. He argued that charitable gifts should be viewed as “separable from the person of its acquirer and possessor.” Money was a neutral object, he suggested, and the donor’s character was irrelevant.

There was risk in subjecting donors “to a public criticism and a private investigation of his whole life and character,” proclaimed an editorial in the Outlook, a religious newspaper that reached 100,000 subscribers across the United States. These influential editors warned readers that if they judged Rockefeller too harshly, wealthy people like him would stop making charitable contributions.

A few people went so far as to encourage gifts from morally suspect individuals.

One anonymous letter writer, in fact, wrote not to be “afraid of ‘tainted money.’” Better for a missionary organization to have the money, this person suggested, than for Rockefeller to keep it for more nefarious purposes.

These arguments won many supporters. The editorial pages of religious periodicals joined the Outlook in urging the missionary board to keep the $100,000.

A prominent opponent

But opponents of Rockefeller’s gift had a notable ally: Washington Gladden.

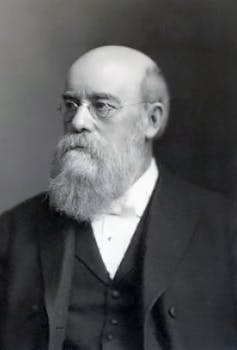

A Protestant pastor from Columbus, Ohio, the 69-year-old was so well known late in his life that one profile in the religious magazine the Independent described “the whole United States” as his pastorate.

Gladden was an early champion of the progressive Christian movement that became known as the Social Gospel. The movement’s leaders urged the restructuring of business and society on Christian principles. Gladden lectured widely throughout the nation and wrote over 30 books on topics ranging from social ethics to Biblical interpretation.

Much of Gladden’s reputation stemmed from his decadeslong critique of large corporations. He blamed greedy corporate leaders for poor conditions endured by the working class. Businesses like Standard Oil were, he argued, part of a “system of industry” causing “social wreckage.”

According to Gladden, one manifestation of this wreckage was in business ethics. In his view, businessmen hid “themselves behind the corporation” and seemingly abandoned whatever moral compass they possessed.

Attacking tainted money

Because of his stature, Gladden was named to the largely symbolic position of moderator of the nationwide Congregational Church. He assumed this role just months before Rockefeller’s $100,000 donation to the church’s mission organization became public.

Gladden demanded the mission board return Rockefeller’s gift.

In his view, the fact that the businessman made his money “within the letter of the law” did not absolve beneficiaries of moral responsibility. Gladden asserted that Standard Oil operated in an “unscrupulous and brutal way … with utter disregard to the ordinary principles of business morality.”

For Gladden, the issue of tainted money affected all institutions that existed for the good of society. No gift, no matter how large, could “compensate for the lowering of ideals and the blurring of consciences” required to accept it. Tainted money inevitably bred tainted institutions, and everyone suffered as a result, he noted.

Despite his fame, Gladden did not win many supporters: Only 25 of 189 American Board of Commissioners sided with him.

The appeal of Rockefeller’s $100,000 proved too great. Given the support it might provide to the board’s missionary activities, the overwhelming majority saw no reason to return it.

The board eventually reached a tacit agreement not to take future donations from figures as controversial as Rockefeller – not exactly the bold repudiation of tainted money that Gladden had wanted.

The unresolved dilemma

Observers in 1905 astutely recognized that the Rockefeller “tainted money” episode had significance beyond a single gift to one organization.

As the editors of a Congregationalist church newspaper noted, the questions their mission board faced “must be answered sooner or later by those who administer any kind of benevolent enterprises.”

Today, institutions that benefited from contributions from Jeffrey Epstein, the Sackler family and other controversial benefactors are having the same realization – and it is spurring similar debates.

David Mislin, Assistant Professor of Intellectual Heritage, Temple University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply