During his three presidential campaigns, Donald Trump promised to run the federal government as though it were a business. True to his word, upon retaking office, Trump put tech billionaire Elon Musk at the head of a new group in the executive branch called the Department of Government Efficiency.

DOGE, as Musk’s initiative is known, has so far fired, laid off or received resignations from tens of thousands of federal workers and says it has discovered large sums of wasted or fraudulently spent tax dollars. But even its questionable claim of saving US$65 billion is less than 1% of the $6.75 trillion the U.S. spent in the 2024 fiscal year, and a tiny fraction of the nation’s cumulative debt of $36 trillion. Because Musk’s operation has not been formalized by Congress, DOGE’s indiscriminate cuts also raise troubling constitutional questions and may be illegal.

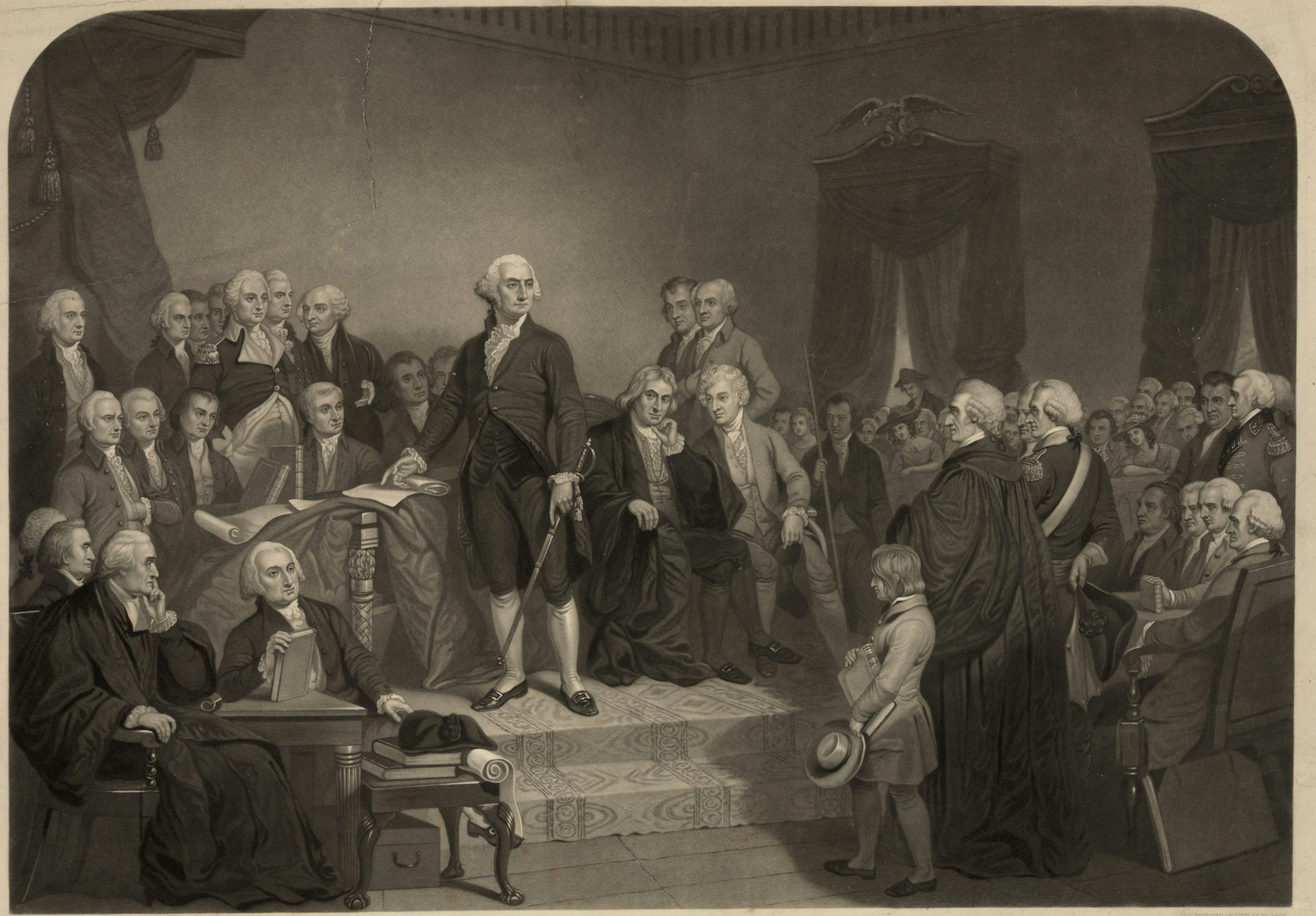

Before they go too far trying to run the government like a business, Trump and his advisors may want to consider the very different example of the nation’s first chief executive while he was in office.

The first businessman to become president

Like Trump, George Washington was a businessman with a large real estate portfolio. Along with property in Virginia and six other states, he had extensive claims to Indigenous land in the Ohio River Valley.

Partly because of those far-flung investments, the first president supported big transportation projects, took an active interest in the invention of the steamboat, and founded the Patowmack Company, a precursor to the builders of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal.

Above all, Washington was a farmer. On his Mount Vernon estate, in northern Virginia, he grew tobacco and wheat and operated a gristmill. After his second term as president, he built a profitable distillery. At the time of his death, he owned nearly 8,000 acres of productive farm and woodland, almost four times his original inheritance.

Much of Washington’s wealth was based on slave labor. In his will, he freed 123 of the 300 enslaved African Americans who had made his successful business possible, but while he lived, he expected his workers to do as he said.

President Washington and Congress

If Washington the businessman and plantation owner was accustomed to being obeyed, he knew that being president was another matter.

In early 1790, near the end of his first year in office, he reflected on the difference in a letter to the English historian Catharine Macaulay. Macaulay had visited Mount Vernon several years before. She was eager to hear the president’s thoughts about what, in his reply, he described as “the last great experiment for promoting human happiness by reasonable compact.”

The new government, Washington wrote, was “a government of accommodation as well as a government of laws.”

As head of the executive branch, his own powers were limited. In the months since the inauguration, he had learned that “much was to be done by prudence, much by conciliation, much by firmness. Few, who are not philosophical Spectators,” he told his friend, “can realise the difficult and delicate part which a man in my situation (has) to act.”

Although Washington did not say why his situation was delicate, he didn’t need to. Congress, as everyone knew, was the most powerful branch of government, not the president.

The previous spring, Congress had shown just how powerful it was when it debated whether the president, who needed Senate confirmation to appoint heads of executive departments, could remove such officers without the same body’s approval. In the so-called Decision of 1789, Congress determined that the president did have that power, but only after Vice President John Adams broke the deadlock in the upper house.

The meaning of Congress’ vote was clear. On matters where the Constitution is ambiguous, Congress would decide what powers the president can legally exercise and what powers he – or, someday, she – cannot.

When it created a “sinking fund” in 1790 to manage the national debt, Congress showed just how far it could constrain presidential power.

Although the fund was part of the Treasury Department, whose secretary served at the president’s pleasure, the commission that oversaw it served for fixed terms set by Congress. The president could neither remove them nor tell them what to do.

Inefficient efficiency

By limiting Washington’s power over the Sinking Fund Commission, Congress set a precedent that still holds, notably in the 1935 Supreme Court case of Humphrey’s Executor v. U.S.

To the displeasure of those, including Trump, who promote the novel “unitary executive” theory of an all-powerful president, the court ruled that President Franklin D. Roosevelt could not dismiss a member of the Federal Trade Commission before his term was up – even if, as Roosevelt said, his administration’s goals would be “carried out most effectively with personnel of my own selection.”

Like the businessman who currently occupies the White House, Washington did not always like having to share power with Congress. Its members were headstrong and independent-minded. They rarely did what they were told.

But he realized working with Congress was the only way to create a federal government that really was efficient, with each branch carrying out its defined powers, as the founders intended. Because of the Constitution’s checks and balances, the United States was – and is – a government based on compromise between the three branches. No one, not even the president, is exempt.

To his credit, Washington was quick to learn that lesson.![]()

Eliga Gould, Professor of History, University of New Hampshire

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply