Journalist, photographer, author and professor Howard W. French’s Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans, and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War, is the most recent in a long career of thoughtful and significant literary and journalistic interventions. It demands an account of modernity that reckons with Africa as central to the making of the modern world.

The book’s main aim, French explains early on, is to restore those key chapters which articulate Africa’s significance to our common narrative of modernity to their proper place of prominence.

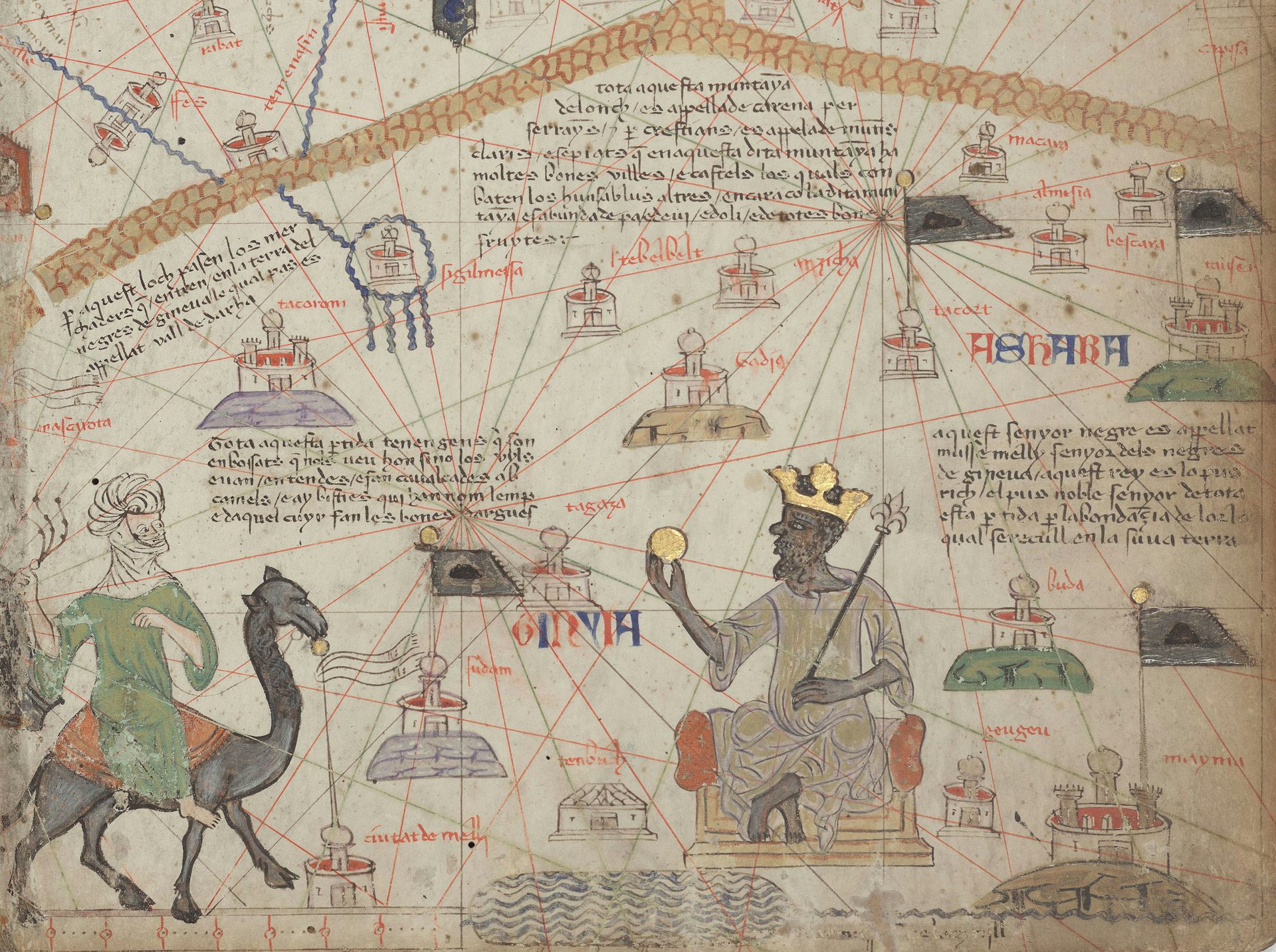

French intricately traces, from the early 15th century through the Second World War, the encounters between African and European civilisations. These, he argues, were motivated by Europe’s desire to trade with West Africa’s rich, Black civilisations. These included the Ghanaian and Malian empires. The ancient West African region was perceived as an abundant source of both gold and slaves. French argues that it is the “intertwined background of gold and slavery” which would eventually birth the transatlantic slave trade of the early 16th century.

A 600 year journey

Born in Blackness sprawls approximately 600 years. It traverses geographies from the edge of Europe, across Africa and the Americas. It follows the long history of the age of European “discovery” beginning with Portugal’s early ventures into Africa and Asia in the late 1400s and early 1500s, through the Atlantic slave trade’s “modest” start in Barbados in the 1630s to the Haitian Revolution.

Then it moves to London’s abolishment of the transatlantic trafficking of humans in 1807 and the introduction of the mechanical cotton picker. This invention “could do the work of fifty sharecropping Blacks, a fact not lost on the white planters of the (Mississippi Delta)”. French’s historical tracing of the crafting of the modern world through the oppression and subjugation of Black persons continues on through the Second World War and beyond.

Citing Simeon Booker, a noteworthy African-American journalist whose work concerned the American civil rights movement and the murder of Emmett Till, an African-American teenager accused of offending a white woman, French notes that in the early 1960s, “Mississipi could easily rank with South Africa, Angola or Nazi Germany for brutality and hatred”.

His careful weaving together of how gold and slavery became intertwined over centuries and continents makes one thing abundantly clear. Without the trade of persons belonging to African civilisations across the globe, but particularly the Atlantic, the modern world would not have been made.

A reckoning with slavery

As the author explains, the boom of the cotton, sugar and tobacco industries of the colonial US simply would not have happened without the trade of slaves from Africa. Without this “capitalist jolt” as French puts it, what we know now as the United States of America would have remained relatively obscure. It would not likely have become the superpower state it is today.

In this way Born in Blackness challenges emphatically the deliberate forgetting of European contests over control of African resources. This process of erasure, French explains, began with Europe’s “Age of Discovery” (1400s-1600s). The improperly explained rationale for this era was that European civilisations wanted to form trading ties with Asia. To do so, they reached across continents, including Africa, for territory – and, later, subjects.

But French insists that the real rationale was Europe’s earnest desire to establish economic ties with Africa, and in particular West Africa with its resource-rich civilisations and resource-based economies.

The intervention of Born in Blackness, then, is to insist on reckoning with the role played by the brutal bond between Europe and Africa. This was forged through slavery. It is what drove the birth of a truly global capitalist economy; it hastened the processes of industrialisation and revolutionised the world’s diets by facilitating the globalisation of the consumption of sugar.

It is also important to mark, as French does, that the centrality of enslaved Africans’ labour extends beyond the mining of plantation crops to the very creation of the plantations themselves. It was the slaves who prepared the land for planting: they removed plants and rocks, but most importantly displaced indigenous peoples from their territories.

A world born in Blackness

In marking this, Born in Blackness demonstrates how the displacement to which African persons taken as slaves is mirrored in the making of modern-day America and echoed in the displacement of first nations or indigenous Americans.

What is at stake in the intervention of the book is precisely what is gestured toward by its title: that modernity and the modern world was indeed born in Blackness. The civilisational transformations the author traces – economic, spatial and most importantly cultural in their texture – are a product of Blackness.![]()

Lauren van der Rede, Lecturer, Stellenbosch University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply