Nations across the world are following a United Nations blueprint to build a more sustainable future – but a new study shows that blueprint leads less to a castle in the sky, and more to a house that needs constant remodeling.

Sustainability scientists have developed systematic and comprehensive assessment methods and performed the first assessment of a country’s progress in achieving all 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) not just as a nation, but also at the regional levels, and not just as a snapshot – but over time.

In “Assessing progress towards sustainable development over space and time” in Nature, scientists from Michigan State University (MSU) and in China show that indeed all sustainability, like politics, is local.

Even as a country can overall claim movement toward a sustainable future, areas within the country reflect the gains and losses in the struggle with poverty, inequality, climate, environmental degradation and for prosperity, and peace and justice. Most striking, the study found, is the disparities between developed regions and ones that are developing.

“We have learned that sustainability’s progress is dynamic and that sometimes gains in one important area can come at costs to another area, tradeoffs that can be difficult to understand but can ultimately hobble progress,” said Jianguo “Jack” Liu, MSU Rachel Carson Chair in Sustainability and senior author. “Whether it’s protecting precious natural resources, making positive economic change or reducing inequality – it isn’t a static score. We must carefully take a holistic view to be sure progress in one area isn’t compromised by setbacks in other areas.”

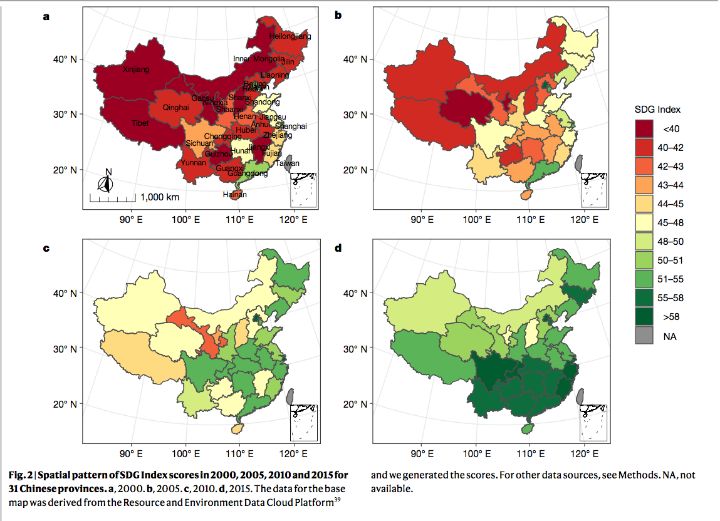

The group assessed China with methods that can be applied to other countries. China’s vast size and sweeping socioeconomic changes at national and provincial levels showed how progress in sustainability can shift. Between 2000 and 2015, China has improved its aggregated SDG score.

At the provincial level, however, there is a disparity between the country’s developed and developing regions. East China – which is home to the country’s economic boom — had a higher SDG Index score than the more rural west China in the 2000s. In 2015, south China had a higher SDG Index score than the industrialized and agricultural-intensive north China.

Zhenci Xu, a recent PhD graduate from MSU’s Center for Systems Integration and Sustainability (MSU-CSIS) who led the study, notes that countries are tasked with urgent goal of achieving sustainability even as populations grow, economies develop unevenly, natural resources like water and energy become scarce, land degrades, and income and gender inequities intensify.

Developed provinces had higher (and thus better) SDG Index scores than developing provinces throughout the study period of 2000-2015. But the average SDG Index scores in developing provinces were increasing faster compared to developed provinces.

“China’s eastern region began developing during the reform and opening-up policy in the late 70s to spur economic development along the coasts, which was accompanied by better social services,” Xu said. “In 1999, China started to address the rural western parts which had lagged in progress. That saw improvements both in infrastructure and ecological conservation, which seems to have boosted their sustainable development. The eastern parts have begun to struggle with the consequences of rapid economic growth – such as pollution and inequities.”

The authors note that overall sustainability is advancing thanks to better education, healthcare and environmental conservation policies. The study points out that even amidst progress, it is important to scrutinize what is happening at regional levels to know where to direct resources and attention.

Leave a Reply