“La Belle Sauvage” is the first volume of “The Book of Dust” series, in which the best-selling fantasy author Philip Pullman returns to the world of “His Dark Materials.”

As a scholar of fantasy and children’s literature, I have been hoping for this novel for 17 years. The original trilogy, which consist of “The Golden Compass,” “The Subtle Knife” and “The Amber Spyglass,” won Pullman multiple awards and devoted fans worldwide. But it also raised heated controversy over its attack on religion as an oppressive institution averse to truth and scientific inquiry. Unlike other fantasy classics in which the evil to vanquish is a supernatural monster or a wicked wizard, Pullman’s Dark Materials reserved that sinister role for the Church.

“La Belle Sauvage” depicts the rise of the tyranny of the Church. It tells a story of how 11-year-old Malcolm saves a baby girl from agents of the Church who mean her harm. On another level, though, the novel continues Pullman’s quest for explaining human consciousness. Put simply, if we have souls, what exactly are they?

What is the soul?

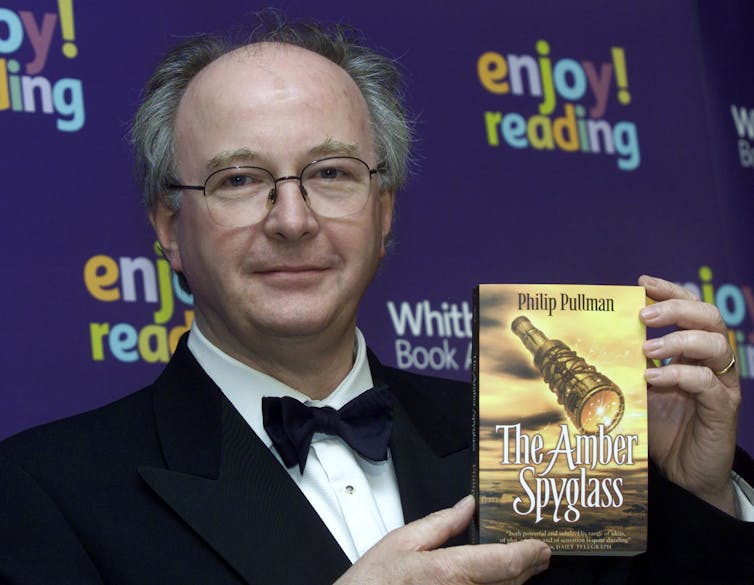

AP Photo/Max Nash

“The Amber Spyglass,” the last book of the first trilogy, crowned Pullman’s assault on religion. It ended with the death of a being who had posed as God and with the collapse of the Church.

Soon after, in a famous address “The Republic of Heaven,” Pullman declared that God is dead in our world too. We must now work together to build a new collective dream to replace the Kingdom of Heaven. As part of that effort, Pullman added, we need to create a new story. This “Republican myth,” as he calls it, must supersede religious explanations with scientific answers to questions about life, death, our origins and purpose.

One of these questions, so far reserved for religion, that Pullman urges the reader to consider concerns human souls. Does the soul exist? What does it look like? Is it the same for everyone? Are souls unique to human beings or perhaps animals or plants have souls too?

Although these questions have long fascinated us, we don’t have an answer. When people look towards religion, they find a number of conflicting answers.

In some religions, the soul belongs to humans alone, in others – every living being has a soul; some traditions insist that the soul is embodied only once, while others speak of transmigration of souls through multiple physical manifestations; some traditions describe the soul as God’s creation, while others as part of God’s essence; some insist that it’s eternal, others – that it is created and can be destroyed.

The problem with these answers is that religious claims are impossible to verify.

However, whereas in our world questions about souls belong in the realm of religion, in the world of fantasy literature souls may be considered as palpable realities. Aware of this potential, Pullman has used fantasy to challenge not so much the existence of the soul as religious claims about it.

Daemons as material souls

In “His Dark Materials,” Pullman created a world in which each human being is born with a daemon: their externalized individual consciousness that takes the shape of an animal. Through the conceit of a daemon Pullman illustrates what’s it like to have a soul and how our souls change as we grow.

Daemons are material beings: crystallizations of consciousness particles that are attracted to and make themselves most fully apparent in humans. Daemons can change shape in children but settle in one permanent shape at puberty. They always take the form of a real-world animal species and of the opposite gender to their human. They seem to be separate beings but are an integral part of one’s self.

For example, a person and their daemon cannot be physically apart by more than several feet. If one of them dies, the other is killed too. Each of these “facts” – and all of them together – add to a consistent, albeit fantastic, exploration of the relationship between the human body, mind and consciousness.

Representing material souls as animals was not without its problems. In particular, Pullman’s use of animal-shaped souls makes it look like social class is inborn. In Pullman’s world one can easily tell a lower-class person by their common animal daemon or an aristocrat by their rare and elegant creature such as a golden monkey or snow leopard. In “His Dark Materials,” the daemon’s species is a “natural” reflection of the person’s deepest self.

But does that imply that some people are “noble souls” by birth alone? That others are born “common souls” and will remain common no matter what?

Material souls and intuitive knowledge

“La Belle Sauvage” continues Pullman’s quest for the mystery of consciousness.

Set 11 years before the events described in “The Golden Compass,” it follows young Malcolm who becomes involved in the resistance movement against the Church. To save baby Lyra from the agents of the Consistorial Court of Discipline, an agency of the Church concerned with heresy, Malcolm steals her away and delivers the baby to her father, Lord Asriel.

One question the book raises and leaves open is how daemons know things without having learned them. Thus, when Malcolm first sees 6-month-old Lyra, who had been left at the Priory to be raised by the nuns, he wonders how many shapes her tiny daemon can take.

Watching the baby and her daemon sleep, another question Malcolm asks is how baby daemons know about animal species that exist in the world. Or how do they know what animal shape would best fit their current state of consciousness? These are questions about what accounts for the soul’s intuitive knowledge that our conscious minds may not be aware of – something that Malcolm and his daemon Asta experience many times across the novel.

Pullman also seeks to amend the implications about rigid class hierarchy of souls he made in the first trilogy. For example, all law enforcement people have wolves or guard dogs as their daemons. Does that mean that when your daemon settles as a dung beetle, your “soul” rules out a career in law enforcement?

By the same token, if a person’s daemon settles as a sleek cougar, does that reveal the individual as a better, higher-class person than someone whose daemon is a squirrel? This determinism drives the first trilogy and humans are said to have no influence on the shape their daemon assumes.

In “La Belle Sauvage,” however, this established “truth” about daemons and human nature is questioned. At one point his Mother’s daemon tells Malcolm that people can do a lot to help determine the shape of their adult daemons. The trick is they will never know that they are doing it.

Material souls for the material world

Pullman has once declared that the death of God and its consequences is “the most important subject” he knows. By addressing questions about the human soul in the secular framework, he argues – in line with materialist science – that consciousness is a material phenomenon.

He asserts that we don’t need religion to remain in awe of the universe. And that we don’t need religion to wonder about the mystery of the soul.

![]() On both of these levels, “La Belle Sauvage” speaks to our age that has separated spirituality from religion. Like “His Dark Materials,” the new trilogy denounces religion in general and Christian belief in particular. The books are anti-religious. But for those who take spirituality to mean human efforts toward achieving deeper self-awareness, they are also works with a profound spiritual message.

On both of these levels, “La Belle Sauvage” speaks to our age that has separated spirituality from religion. Like “His Dark Materials,” the new trilogy denounces religion in general and Christian belief in particular. The books are anti-religious. But for those who take spirituality to mean human efforts toward achieving deeper self-awareness, they are also works with a profound spiritual message.

Marek Oziewicz, Professor, Literacy Education, University of Minnesota

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Leave a Reply