By the late 1950s foremost musicians like Charlie Parker, Charles Mingus and John Coltrane explicitly introduced politics in their jazz, as the civil rights movement started gaining momentum in the US. Musician and author Gilad Atzmon explained it in a 2005 essay:

Black Americans were calling for freedom, and jazz expressed it better than mere words.

This trend continued and intensified over the following decades, especially in free and spiritual jazz. These sub-genres represented an angrier battle for political freedom.

Profoundly beautiful

In 1969 avant garde jazz vocalist Leon Thomas, with spiritual jazz giant Pharoah Sanders, composed “Malcolm’s gone”. It’s a profoundly beautiful tribute to American civil rights activist and revolutionary, Malcolm X, who was assassinated in 1965.

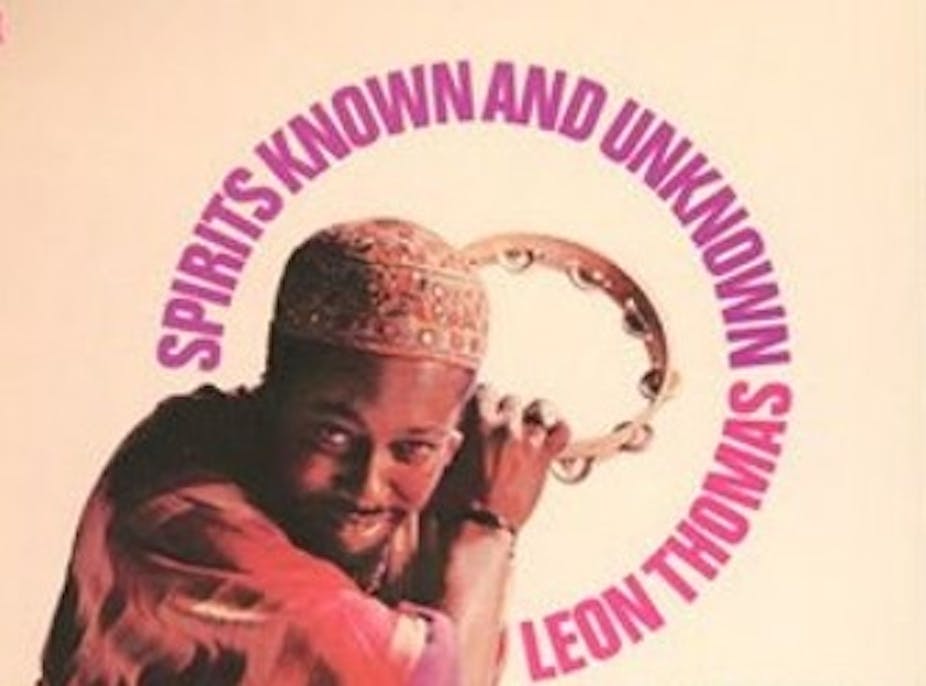

The song appears on Thomas’s debut solo album, “Spirits Known and Unknown”.

It features Sanders (on tenor sax) and other free jazz luminaries like Cecil McBee (bass), Lonnie Liston Smith (keyboards) and Roy Haynes (drums).

Thomas is often a forgotten figure in popular music. He’s best known for his unique jazz vocal style that is characterised by the experimental use of yodelling and scatting, along with his own beautiful natural voice.

The singer, who died in 1999, is mostly remembered for his contributions to the recordings of jazz and rock heavyweights such as Randy Weston, Rahsaan Roland Kirk, Oliver Nelson and Carlos Santana. That is despite the gravity of Thomas’s own solo work and his contribution to jazz, especially in the area of vocalisation.

Seconds of silence

Thomas’s opening line, to the mostly instrumental “Malcolm’s gone”, is simply the utterance “Malik El-Shabazz”, X’s assumed Muslim name at the time of his death. It’s then followed by a few seconds of silence before the band starts playing a deeply melancholic melody. The melody is the sonic equivalent of the emotions that one feels upon hearing of the passing of a loved one.

Thomas rejoins the melody about two minutes later with the line:

I know he’s gone… but he’s not forgotten.

I know he died just to set me free… yes Malcolm’s gone, but he’s not forgotten, he died just to save me, give me back dignity.

Thomas then explodes into a yodel. His gloomy wail is set to a striking cacophony of beautifully layered rhythms and melodies. The song then transcends into what resembles a spiritual jazz version of a Pentecostal funeral service. It ends with the ululating congregation honouring the late Malcolm X by clapping in unison.

The song invokes the imagery of masses of mourning people at a funeral. At the same time it creates an atmosphere of jubilation reminiscent of a congregation experiencing glossolalia and spirit possession collectively.

Sonically it draws on various black spiritual traditions to express, in sound, the emotion of losing a well loved and respected member of the Ummah, or the Muslim community. The lyrics clearly draw parallels between X and Jesus Christ, which some may regard as the ultimate tribute, or perhaps a very strong political statement given the sociopolitical climate of the USA during that period.

A volatile period

The late 1960s, the period when Thomas released the song, was a very volatile period for African Americans. It marked the end of the relatively nonviolent American civil rights era, and the beginnings of the militant Black Power movement.

Many black people at the time felt that the passive resistance of the civil rights era was no longer a viable option in their quest for equality. Cue an ideological shift toward the black nationalist, Pan-Africanist and socialist ideologies offered by the Black Power movements, hellbent on protecting themselves by all means necessary against an oppressive state.

It was also when many influential and leading figures were either silenced, imprisoned or assassinated. The situation was further exacerbated by the Vietnam War and the Nixon-era conservative politics.

“Malcolm’s gone” is not only a song that pays tribute to one of the most influential black freedom fighters to walk this planet (which in itself is a revolutionary act). It’s a song that dares to liken him to the very same deity that racist nationalist white America prayed to at night, Jesus Christ. This was a very provocative act given America’s Christian foundations, and the fact that Malcolm X, a black Muslim, was perceived to be an enemy of the state.

With minimal lyrics and a robust otherworldly feel the song is able to capture the pain and optimism of black America in a time of great adversity. At the same time it consolidates ideas of civil rights pacifism (through the imagery of Christ) and Black power militancy (in the form of crashing instruments and wailing). It is a profound expression of the black condition of the time, and a deeply dignified tribute to a fallen soldier.

![]() Protest music has made a serious comeback over the past five years. This article is the second in a series featuring Songs of Protest from across the world, genres and generations.

Protest music has made a serious comeback over the past five years. This article is the second in a series featuring Songs of Protest from across the world, genres and generations.

Michael Shakib Bhatch, Lecturer of English. PhD Candidate in Afrofuturism and African Studies, University of the Western Cape

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

Leave a Reply