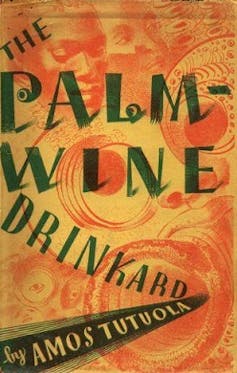

In 1952 The Palm-wine Drinkard became the first West African novel written in English to be published internationally. That it was written by Amos Tutuola, an unknown Nigerian clerk who took to writing to alleviate boredom, meant the book caused a stir. To this day, it’s celebrated as a key example of African fantasy.

But more recent analysis suggests that the Western view of Tutuola as a fantasy writer is slightly patronising, because it overlooks how seriously his work engages with African reality on its own terms.

Similarly, my reading of the novel explores how it is more suitably classified as a pioneering work of African science fiction than of fantasy. And a lot of that has to do with the way Tutuola uses language. Fantasy deals in the mythic and supernatural. Science fiction is an invention more grounded in reality. I suggest that the lazy appeal to African fantasy and folklore is in line with a longstanding dismissal of Africans as technological beings and, by extension, writers of science fiction.

What the book’s about

The Palm-wine Drinkard introduces us to the Drinkard, who passes his time drinking palm wine with his friends. The alcoholic drink is made from the sap of palm trees, collected by a tapster.

Then his beloved tapster dies after falling from a tree. No longer able to access palm wine, the Drinkard soon loses favour with his friends.

He resolves to bring the tapster back from the place where all dead souls go – Deads’ Town. He passes through many strange towns, meeting bizarre creatures on his journey before finally reuniting with his tapster. Only to learn that a dead person cannot leave Deads’ Town.

Bereft, the Drinkard returns home. Having matured on his journey, he is no longer a nonchalant drunkard and demonstrates his newfound sense of civic duty by bringing an end to a famine in his village.

Western critics hailed The Palm-wine Drinkard as inventive and avant-garde. But Nigerian critics were puzzled and even embarrassed by Tutuola’s use of English. They argued no such English existed, even in a purely spoken form.

Putting the debate of literary quality aside, Tutuola’s striking use of language is undoubtedly sublime, able to transport the reader in ways that are necessary and expected for science fiction. He takes great pains to place his narrative within lived and believable African experience that is more in line with science fiction than fantasy.

Creating a sci-fi world

Samuel R. Delany is a luminary African-American science fiction writer and critic. For him, science fiction is able to “generate the infantile wonder” of the reader through language.

In his hallmark essay About 5,750 Words, he gives an insightful explanation of how science fiction is distinct from other types of fiction. Where realism tells what “could have happened” and fantasy explores what “could not have happened”, science fiction opens up space for events “that have not happened” yet.

Fantasy can travel anywhere, but science fiction approaches the world with an inventive attitude rather than a fanciful one. Science fiction can stretch outside our current world, but never to the extent of fantasy. As Delany explains, science fiction writers very carefully use language as part of a process that helps the imagination make the leap from our world into an alternative one.

Tutuola is invested in this balancing act: he stretches the limits of realism but also reins in the unlimited possibilities of fantasy. For example, the Drinkard explains that he and his wife became immortal because they “had ‘sold our death’ to somebody at the door for the sum of £70: 18: 6d and ‘lent our fear’ to somebody at the door as well on interest of £3: 10: 0d per month, so we did not care about death and we did not fear again”.

Tutuola imagines a refreshing option where states of existence like death and anxiety – much like everything else in our consumerist culture – can be traded or rented and “worn” like clothing. Giving the exact amounts in British pounds marries something as familiar as shopping with the wondrous potential that we may one day discard existential inconveniences as easily.

For every fantastic suggestion, Tutuola provides a real-world equivalent. He places the most bizarre creatures within the limits of our current experience.

In the forest the Drinkard meets a creature whose two large eyes “were as big as bowls” and feet as “long and thick as a pillar of a house”. This reliance on similes or mundane comparisons is part of an effort to weave the fanciful into the reader’s reality.

The Palm-wine Drinkard uses language in ways that critics like Delany insist are universally crucial to science fiction.

African sci-fi and fable

Some contemporary appraisals of science fiction in Africa argue that the genre is rooted in indigenous fable and folklore and should be read on unique – exceptionalist – terms.

Yet reading African science fiction as an exclusive – and even resistant – form of science fiction, we lose sight of the globalising spirit that’s central to understandings of popular culture in Africa.

Wielding language as the ultimate form of technology, Tutuola has reassembled it and built a vocabulary for his pioneering work of African science fiction that can easily be read as a worthy participant on the global stage of popular genre fiction.

This article is based on Moonsamy’s chapter in the new book Literary Afrofuturism in the Twenty-First Century from The Ohio State University Press.![]()

Nedine Moonsamy, Senior Lecturer, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply