The NFT acronym has entered the common lexicon in the last few months thanks to a series of ventures that have made non-fungible tokens – “NFTs” – something of an avant-garde symbol of wealth. Brands are eyeing NFTs with fascination, and the rise of these unique digital tokens are dominating headlines across the globe. Yet, relatively few really know what they are, and even fewer understand their practical uses.

In reality, NFTs are “ownership” certificates for corresponding works, which means that unless otherwise specified, the buyer of an NFT only buys proof of a right to the work secured through a smart contract. Unfortunately, this explanation does not really help us to understand the phenomenon better. Smart contracts have existed since the 1990s and are, in essence, computer protocols that facilitate, verify or enforce contracts’ negotiation or execution. Additionally, digital works (and more specifically, the digital files at play) have existed since the 1960s.

With this in mind, it is worth wondering what exactly the new element that that has made two long-known elements so interesting now. The answer is the blockchain, which is another term that has entered common parlance, although not all who use the term fully understand it. First conceived by Satoshi Nakamoto, blockchains “provide a place to put information that anyone can add to, that no one can change, and that isn’t controlled by any single person or entity,” as the Verge’s Mitchell Clark put it. “Instead of one company or person keeping track of everything, that responsibility is spread out to everyone on the network.” (As Clark points out, the system that is blockchain is, of course, much more complicated than that.)

NFTs are certificates of “ownership” of a work guaranteed by a multiplicity of operators in a network that constantly keeps track of the information provided to it; sharing the same information among numerous operators makes it impossible to change that information with detection. It is worth mentioning that there is no single blockchain platform that certifies validity. Indeed, several blockchain platforms are available (including the heavily relied-upon Ethereum), but they all rely on the same underlying principle. The guarantee offered by the blockchain applies to transactions carried out on it but not to transactions involving the same work carried out on different platforms.

Despite the ethereal nature of NFTs, the interest that these new IT/legal/artistic tools have spurred is very much tangible. So far, most companies have used NFTs for promotional purposes or to monetize their creative assets. Meanwhile, brands such as Nike, Louis Vuitton and F1 Racing have shown an increased interest in these digital collectables, which open up new and unexplored avenues for marketing and promotion. Another prominent example is Coca-Cola, which has a long track record of creating and selling collectables in the “real” world. On the company’s website, a limited-edition set of four Norman Rockwell Coca-Cola prints is priced at $400, while a vintage German “Trink” plastic cooler can be bought for $550.

Now, Coca-Cola is selling a series of four NFTs, including a pixelated version of Coke’s classic 1956 vending machine, a metallic red bubble jacket inspired by the company’s old delivery uniforms, a digital version of Coca-Cola’s 1940s trading cards and a “sound visualizer” that features classic Coke sounds, such as a bottle opening, and a drink being poured over ice. Proceeds will benefit the Special Olympics International, while the publicity will benefit the Coca-Cola Company.

A Tool for Brand Owners

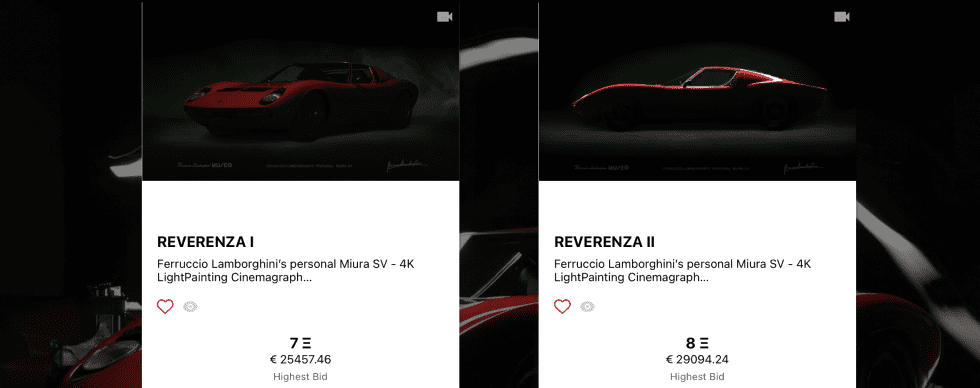

Despite their collectable nature, NFTs are not just collectors’ items like Coca-Cola gadgets or Lamborghini model cars. NFTs can become a tool for brand owners to harness the growing possibilities of the so-called metaverse, such as in the realm of Fortnite, the online video game created by US video game and software developer and publisher Epic Games. Players must work together to stop growing waves of aliens that have conquered earth in a post-apocalyptic future.

The aim of the game – which connects tens of millions of players worldwide – is to kill as many enemies as possible, including by teaming up with other players. The collaborative component of the game has helped to create a virtual universe where players know each other, strategize, make friends, and spend time together as they build their virtual reality. Fortnite has become so popular over the years that in August, pop singer Ariana Grande organized a virtual concert for millions of Fortnite users only. Meanwhile, Balenciaga recently partnered with the game for a heavily-hyped collaboration, as has artist KAWS, who recently revealed a Halloween centric tie-up.

While entrance into the world of Fortnite is free, Epic Games generated more than $9 billion in revenue from the game between 2018 and 2019 thanks to in-game purchases. Using the local currency, V-Bucks, which is bought with real bucks, players can purchase in-game “skins” and tools to enhance the look and their activities in the virtual world that is Fortnite.

Although it is easily one of the most prominent players in the metaverse, Fortnite is undoubtedly not the only virtual world that consumers can engage in. From this perspective, the opportunity to cater to consumers and sell virtual versions of tangible products in these virtual environments is proving to be increasingly attractive to companies of all kinds. Fortnite may be a good market for skins, work tools, weapons, etc., but the model can be – and in some cases is readily being – applied in other instances. Gucci’s successful foray into the Roblox universe comes to mind, as does Burberry’s partnership with Mythical Games’ Blankos Block Party.

As for additional ways for brands to connect with consumers in the metaverse, it is not impossible to imagine video game players being tasked with organizing a virtual fashion show, where NFT ownership of fashionable clothes would be a crucial plus. To attract car enthusiasts, automakers may team up with a game to enable consumers to participate in a car race using a unique car model purchased by way of an NFT.

Still yet, there is the augmented reality world, where reality is enriched by electronic devices with virtual elements that alter the user’s vision. This technology – which aims to provide users with more information about what they see (such as the direction of the road ahead or the immediate translation of road signs into another language) – also allows users to observe themselves and/or others that are wearing a pair of virtual-only Gucci trainers, for instance, or perhaps, exclusively virtual Chanel sunglasses.

Gucci, which is proving to be an innovator in this field, has already created its first pair of designer trainers that can only be worn online thanks to Wanna, the fashion-tech app created by Belarusian design studio. These virtual kicks are free and available to everyone, but one can imagine brands requiring payment for such offerings and thus, making these offerings much more exclusive thanks to the same technology.

The amalgamation of these virtual worlds, and the intersections between the “real” world and virtual world are what is increasingly being referred to as the “metaverse.”

Potential Legal Issues

With enduring interest in NFTs, virtual fashion, and the metaverse as a whole, it is easy to see why brands are beginning to rush to find ways to get involved. But this digital development does not come without complications. NFTs, for instance, have enormous potential, including as a way to open up new revenue streams for companies that so far have focused on physical products. However, the very system upon which NFTs are based is inherently flawed, at least from a legal point of view, and can certainly not replace, at least to date, the standard intellectual property protection tools that intellectual property owners rely on.

Primarily, the value (uniqueness) of an NFT does not hinge on blockchain technology. Instead, it depends on the level of trust between the seller and the buyer. While the blockchain platform at play guarantees that the exact digital token and any corresponding digital or physical work has not been sold to others on the same platform, it does not make the same guarantee for other blockchain platforms. As such, the buyer must assume that the seller has not already sold or does not intend to sell the work through other channels.

Additionally, although the blockchain prevents multiple sales of the same work, it permits an unlimited number of near-identical works to be offered on the same platform. Therefore, the rightful acquisition of an NFT, including ownership of any corresponding works, is only guaranteed to the extent that the seller acts in good faith, and the blockchain platform verifies that its system is not being used for fraud. It is easy to see the room for potential foul play on this front.

Then there is the issue of obsolescence. Blockchain platforms are thriving on heavy promotion, and if we are to believe crypto-enthusiasts, then it is safe to assume that these platforms will continue to function for a long time. That does not mean, though, that all NFT blockchain platforms will be equally successful. Just as in the case with other tech platforms, some blockchain platforms could cease their operations in the future, and with that, delete the recorded transactions in their systems.

Real Contracts in the Digital World

Against this background, when an individual or other entity purchases an NFT (e.g., a graphic that it plans to use on its website), it must resort to the usual contractual tools to respond to the system’s intrinsic shortcomings. As such, a contractual relationship with the artist is crucial in order to transcend the digital tool’s potential technical limitations and protect the buyer from fraudulent conduct.

Issues, such as the sale of copies on other blockchain platforms or the sale of similar versions of the work, must be adequately addressed in the contract that is entered into in connection with the purchase of an NFT; likewise, the rights of economic exploitation of the work, which are not automatically transferred with the transfer of ownership of the work itself, must be appropriately regulated by contract.

An interesting example is the NFT for a video of a slam dunk by LeBron James, which was released as part of a series of limited-edition digital collector’s cards of NBA highlight clips that can be bought and sold on the Top Shot marketplace. NBA Top Shop cards depicting LeBron’s dunks may sell for large sums of money (one such NFT sold for a record $387,600 in April), but that does not mean the cards come without strings attached. For instance, the NBA still owns the copyright in the original video, and any reproduction of that video is still subject to licensing terms from the NBA. Beyond that, LeBron still maintains rights in the use of his likeness, as well as his trademark-protected name.

As such, it is advisable to carefully check the contract terms that govern the purchase of individual NFTs, and when possible, select more structured and sounder blockchain operators.

At the same time, if a rights holder – such as a copyright or trademark owner – issues NFTs, the most pressing issue for the seller will be protecting the any rights that are integrated into the NFT. While the blockchain system on which NFTs are based guarantees the uniqueness of the work, it does not guarantee that third parties cannot market the same work with irrelevant modifications on the digital code underlying the image. It also does not guarantee that others cannot sell the same creation on other blockchain platforms. From this perspective, a copyright registration that governs the aesthetic characteristics of the work included in the NFT and a registration of the trademark in the most appropriate class are just as integral in the virtual world as they are in the real world.

In this same vein, when a rights holder transfers an NFT to a purchaser, the exclusive rights transferred to the purchaser must be contractually defined by precisely identifying what uses of the digital work are possible and which ones remain the exclusive rights of the transferor. A contract outlining these terms must then be administered, saved, and managed through the blockchain platform (by way of a so-called smart contract), with the drafting of that contract requiring the same attention and care as a contract written with pen and paper.

Andrea Cappai is the head of Bugnion SpA’s Internet Department, where he oversees the management of services providing online protection of intellectual property.

Leave a Reply