Photos of civilians killed or injured in the Russia-Ukraine war are widespread, particularly online, both on social media and in professional news media.

Editors have always published images of dead or suffering people during times of crisis, like wars and natural disasters. But the current crisis has delivered many more of these images, more widely published online, than ever before.

“It’s all over social media,” says Nancy San Martin, a longtime former foreign correspondent and editor at the Miami Herald. And not just online. Mainstream journalists are also departing from their traditional tendency to avoid prominently featuring images of dead people or particularly direct depictions of physical injuries.

But in times of conflict overseas, those standard practices tend to ease, San Martin, now deputy managing editor for the history and culture desk at National Geographic, told me in a phone interview: “War will always open that door. Part of our role is to document the consequences of war and all that it entails.”

Editorial oversight has traditionally been part of the equation – the practice of a group of journalists who ensure context, balancing the significance and importance of what an image depicts with its gruesomeness. They might, for instance, choose a different angle of an injured or dead person that shows less blood, or crop an image so a dead person’s face isn’t visible, or choose to withhold an image altogether while providing written information about what happened.

As a longtime journalist and editor following media, journalism and human rights, I

know images can become public icons symbolizing major events.

The flood of images from the Ukraine war runs deep and wide. It contains many potentially iconic images but also shows more raw carnage than in past conflicts.

Powerful images

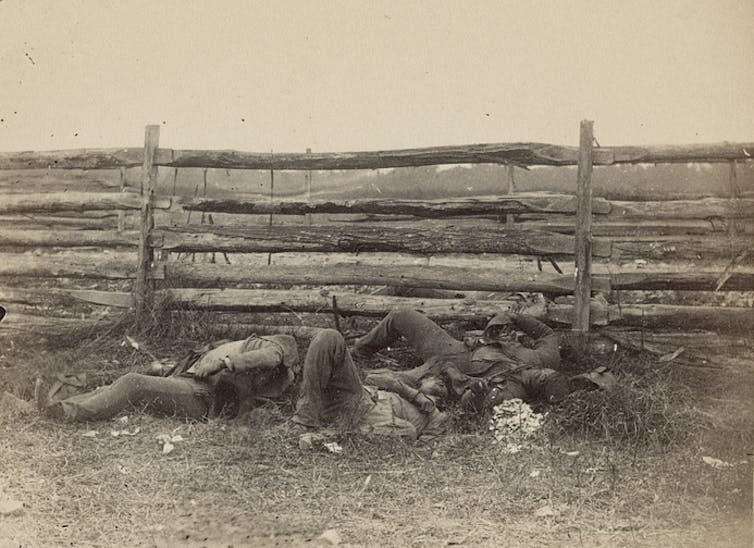

From the earliest days of photography in the 19th century, war has been a common subject, including during the U.S. Civil War.

Certain images have become famous, such as Joe Rosenthal’s World War II image of U.S. Marines raising the flag on Mount Suribachi, signaling the capture of Iwo Jima from the Japanese Imperial Army in February 1945. It was distributed by The Associated Press and ran on the front pages of many U.S. newspapers.

“There have always been powerful images emerging from conflict,” Pulitzer Prize-winning photographer Patrick Farrell told me in a video call. “A still image is still one of the most powerful forms of media. It will sit with you forever.”

Many of the famous images are not of victory or glory but rather of violence and death – and also remain etched in public memory. Nick Ut’s photograph of “napalm girl” Kim Phuc and John Filo’s photo of Mary Ann Vecchio mourning student protester Jeffrey Miller at Kent State University show both the foreign and domestic toll of the Vietnam War. They were transmitted via wire services, too, and chosen to feature prominently in newspapers and magazines across the country.

Photos of bodies piled in the streets after the devastating earthquake in Haiti in 2010 and floating in the water in New Orleans after Hurricane Katrina in the same year are examples of the choices made by editors across the nation to feature coverage showing the real human cost of significant natural disasters.

Kevin Carter’s 1993 image of a vulture next to a starving child in Sudan is another lasting image of human tragedy that was published by editors worldwide. It won a Pulitzer Prize in 1994.

Wire-distributed photos of other tragedies, including Nilufer Demir’s image of Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian boy whose body washed up on a Greek beach, and atrocities, like the images from Abu Ghraib of U.S. military personnel abusing Iraqi prisoners, are also visceral reminders of complex events.

Increased volume

The difference between those situations and the present one in Ukraine is the sheer volume of images.

There are, as usual in conflict situations, award-winning professional photojournalists in Ukraine sending images back to the media outlets they work for. But many of them are also posting images on their own or their employers’ social media accounts – more images than might be published on a newspaper’s front page or homepage on the web.

Also on social media are legions of ordinary citizens taking pictures with their smartphones and bearing witness, sharing countless images every day.

With the “floodgates opened by social media,” as Farrell put it, the media environment in 2022 is different from previous decades. There are now many powerful images competing to become iconic.

It’s “not more graphic than what we saw during Vietnam,” in Farrell’s estimation, but the media cycle then, based on daily newspapers and nightly TV news broadcasts, meant there were breaks in the barrage of imagery.

What’s of concern to Farrell, and to me, is that there is less editorial oversight about which images reach the most eyeballs – even in professional newsrooms.

With social media in the mix and the never-ending competition to be first, editors are publishing and distributing images with less consideration for traditional editorial restraint and balance between gore and meaning – and with less context about the images themselves.

Context is vital

An important element of that context is that in some ways life goes on, says San Martin. Despite the carnage and mayhem of war, she says, the places experiencing war are still places where people make their lives. Her husband, Joe Raedle, an award-winning photographer with Getty Images, has been on the ground in Ukraine documenting both the refugee exodus and everyday life – cultural performances, restaurants serving free meals, churches providing comfort – and a man playing a piano on the street, having left his own behind when he fled the fighting.

“It’s a different kind of war. Still heartbreaking,” she says, noting that there is more happening than the dominant images show. Those elements, she predicts, will become more important to full coverage of events in Ukraine as the war continues. It is going to be, as she says, “a long haul.”

It’s normal for media to focus on the immediacy of conflict or disaster and to highlight the most dramatic, even horrific events. But what San Martin reminds me, and what I have seen in my work, is that the journalists often give less emphasis to the processes behind events and the surrounding context – including the survival, determination and resilience of those affected.

Sensational images circulating on social media are similarly incomplete – or even potentially false, whether shared by propagandists or their innocent dupes. They represent an important, and alarming, reality. But there’s more to the picture than that.![]()

Beena Sarwar, Visiting Professor of Journalism, Emerson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Leave a Reply