Gratitude is a strong emotion, usually felt by a person who benefits from an intentional good deed of another person. Receiving gifts or benefits can instill a feeling of gratitude in people who receive them, i.e., beneficiaries, encouraging them to be more prosocial, while also helping to create a bond with their benefactors. This has led several researchers to examine the determinants of gratitude. Interestingly, beneficiaries often have preconceived beliefs about receiving a benefit. For instance, they may have no prior expectations of receiving a ‘surprise’ gift or could counterfactually imagine the absence of those benefits, despite receiving them. Although several studies have investigated the connection between expectations or counterfactual thinking and gratitude, there is insufficient information on whether imagining the absence of benefits increases beneficiaries’ gratitude upon receiving them.

In both studies Dr. Yamamoto and his co-author Masataka Higuchi, also from Sophia University, provided participants with manipulated vignettes to read as part of the simulations. While some participants received vignettes with absence simulations (absence simulation group), others received vignettes without absence simulations (control group). All participants were social psychology students at a Japanese university.

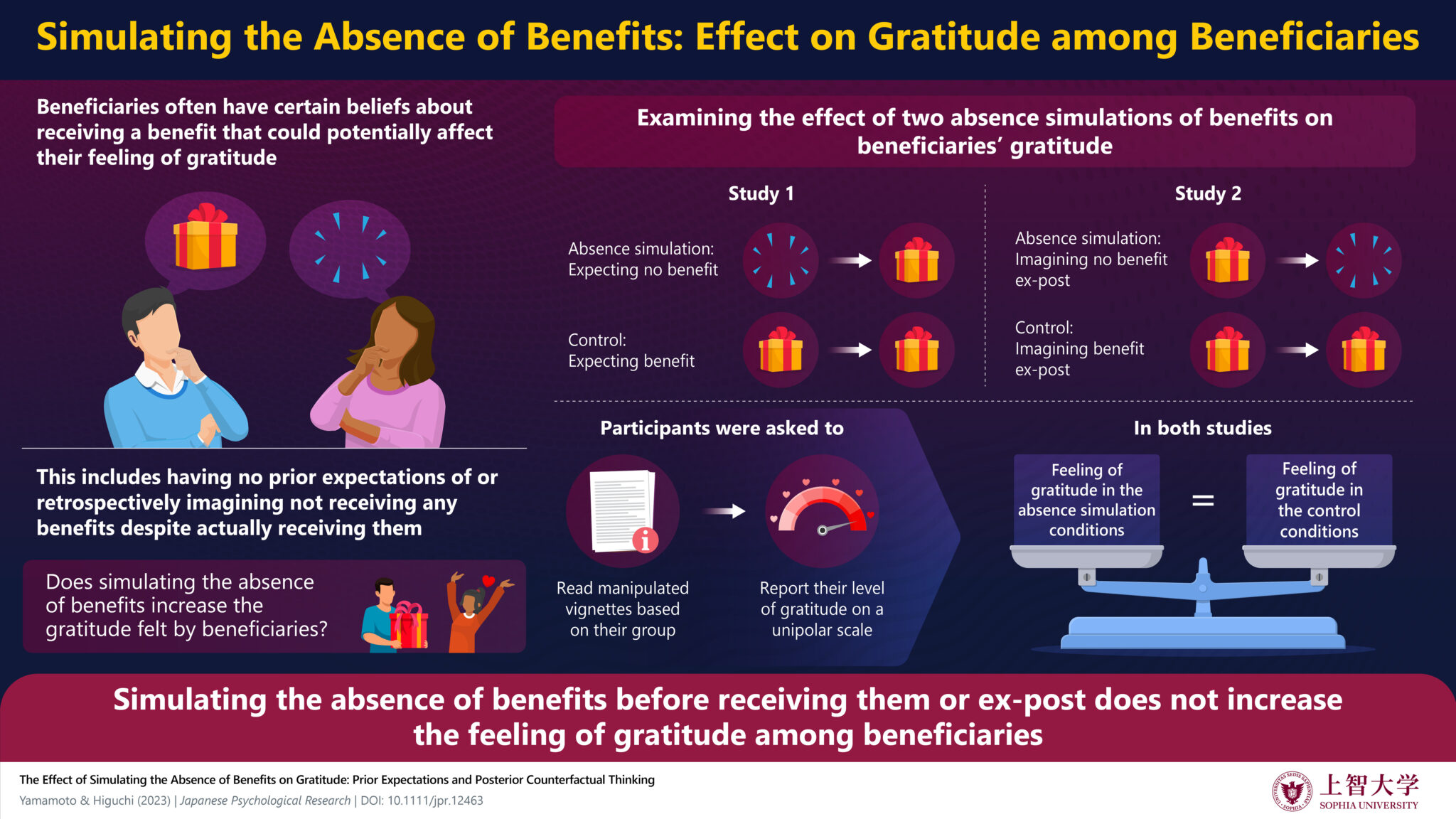

To this end, a study published in Japanese Psychological Research on 07 July 2023 investigated whether simulating the absence of benefits increases beneficiaries’ gratitude, via two psychological experiments. “Study 1 examined the effect of prior expectation of not receiving benefits, and Study 2 examined the effect of posterior counterfactual thinking regarding the benefits, with the hypothesis that simulating the absence of benefits increases gratitude in both studies,” explains lead author Dr. Akitomo Yamamoto, a Postdoctoral Fellow at the Faculty of Human Sciences, Sophia University. “These studies are part of a continuous investigation into whether gratitude, which is an emotional response to others’ benevolence, can be influenced by factors unrelated to the nature of the benevolence itself,” he continues.

In the first study, participants were presented with a scenario where a beneficiary (the participants themselves) may receive a gift from a benefactor. The absence simulation group is then informed that the benefactor did not prepare a gift—ergo setting no prior expectation of receiving a benefit. In contrast, the control group was informed that the benefactor did seem to prepare a certain gift. In the final vignette, both groups were told that the beneficiary receives the gift. Subsequently, the participants were asked to rate their gratitude on a nine-point unipolar scale (0-8).

In the second study, the participants read a vignette where a beneficiary (the participants themselves) received a certain benefit from a benefactor. The absence simulation group was then asked to imagine not receiving the benefit and the control group was asked to again imagine the benefit-receiving event. Both groups were asked to note down the consequences of their respective simulations and rate their gratitude.

Interestingly, the research team found that in both studies, simulating the absence of benefits did not significantly increase the participants’ gratitude as compared to the respective control groups. This negates the researchers’ original hypothesis and instead suggests that simulating the absence of benefits does not increase the beneficiaries’ feeling of gratitude.

These findings can help enhance our understanding of gratitude and how beneficiaries’ beliefs may or may not control this emotion. They could also have implications for the practice of gift-giving. “Our findings suggest that infusing your gifts with genuine thoughtfulness for the recipient, rather than focusing on peripheral elements like making it a surprise, is essential to make the recipient feel grateful,” concludes Dr. Yamamoto.

Leave a Reply