From An-My Lê and Zoe Leonard to Emilija Škarnulytė and Nguyen Trinh Thi, artists are turning to rivers to illuminate the fluidity of life on earth

Fourteen vertical, black-and-white photographic landscapes compose Fourteen Views (2023), a cyclorama created by Vietnamese-American photographer An-My Lê for her survey show at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Taken between 1994 – the year Lê first returned to Vietnam after being airlifted out of Saigon in 1975 – and 2022, each image connects at the horizon line. Locations span the Mekong and Mississippi rivers and deltas, with views of Parisian parks in between. Images include a picture of the Bản Giốc waterfalls at the Vietnamese-Chinese border, a yellowwood in Paris, of the variety brought to France from an American plantation, and a bald cypress tree rising up from the water in Louisiana.

As a composite landscape, Fourteen Views visualizes the title of Lê’s MoMA show, ‘Between Two Rivers/Giữa hai giòng sông/Entre deux rivières’, whose trilingual construction expresses the geopolitical triangulation that defined 20th-century Vietnam as a French colony and Cold War frontline, causing the displacement of Lê’s family and so many others. The idea for the work emerged in 2021, when Lê stood on a perch with a 360-degree view of a US military exercise ‘happening in all directions’ in the Californian desert – the same location where Lê spent 3 years photographing soldiers being deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan for 29 Palms (2003-2004). Suddenly, she felt a rush of all-encompassing grief, she writes in her MoMA catalogue. She visualized ‘the wide and intractable arc’ of her ailing mother’s life, and contemplated ‘the intertwining play between her destiny and the inexorable unfolding of American foreign policy…’

Fourteen Views translates that dizzying collapse of historical, geopolitical, and personal scales. Deconstructing what Lê describes as the landscape genre’s 19th-century imperialist origins, when land was recontextualized into colonial property, the work illuminates the far-reaching implications of colonization and war on body, soul, and land. Resisting the stasis of linear time and space, Lê treats the river as both a metaphor and a reality. Always moving, never settling, yet always connected, it is the embodiment of a fluvial, diasporic journey that meanders through geographies, histories, and stories. Take the Mekong River, which runs from the Tibetan Plateau through Southwest China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. Or the Mississippi River, the largest drainage system in North America, which, as Mario García Torres points out in his 2017 lecture-performance, Five Feet High and Rising, is ‘not only a theater for history’ but ‘the setting for a long list of fictional tales.’

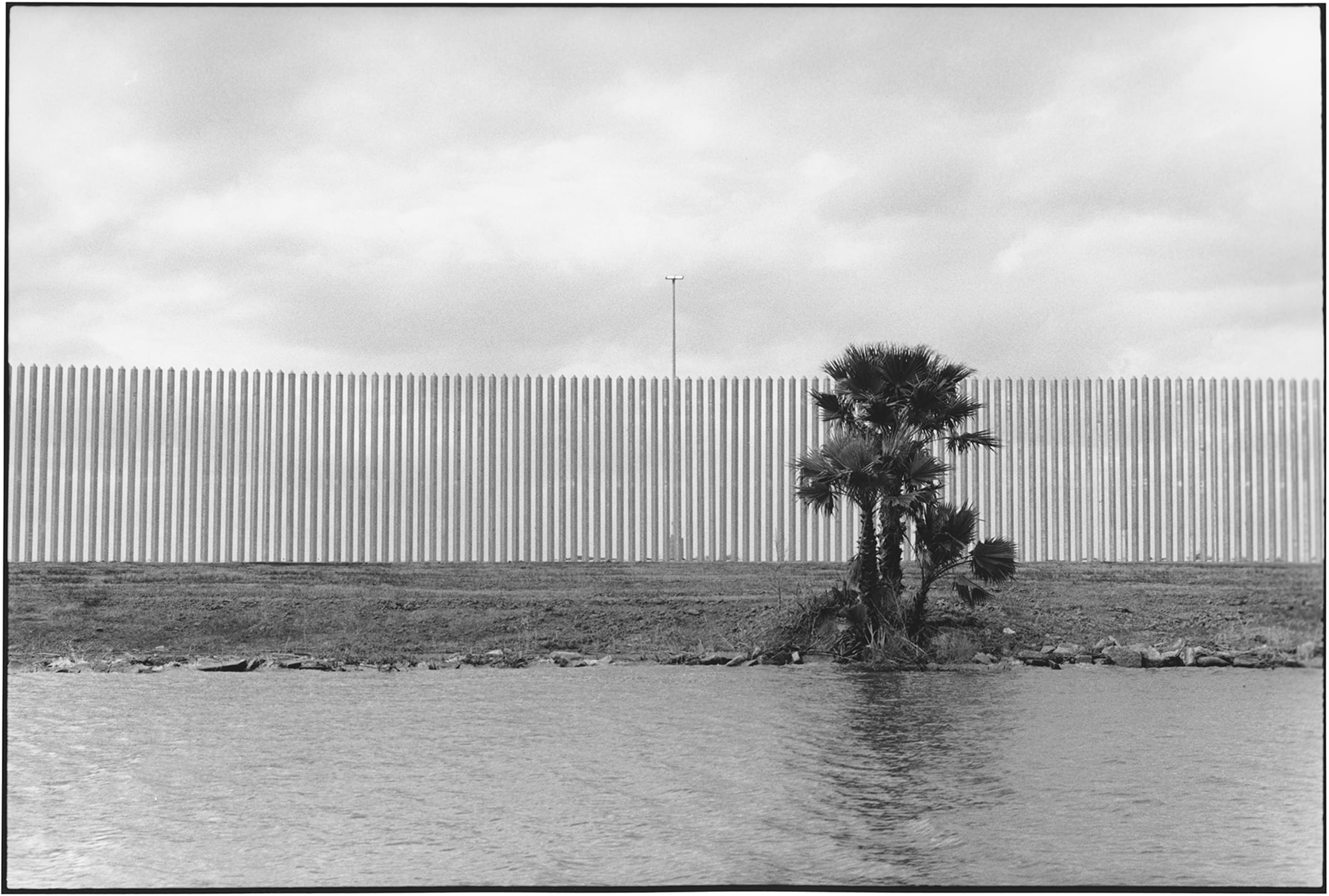

First presented at the 13th Sharjah Biennial in 2017 as both a lecture and an audio recording within an installation of found landscape paintings housed in a straw shack, García Torres describes Five Feet High and Rising as a study of the esoteric and cultural history of rivers. It unfolds as an accumulation of aphoristic reflections on songs and movies referring to real and metaphorical rivers, from the Jonny Cash song Five Feet High and Rising to Dean Martin’s recording of Rio Bravo, referring to the Rio Grande – the subject of Zoe Leonard’s recent exhibition ‘Al río / To the River’. Presented in autumn 2023 at the Museum of Contemporary Art Australia in Sydney, black-and-white photographs cover the 2,000 kilometer section of the Rio Grande that defines the border between Mexico and the United States. Taken over 5 years starting in 2016, Leonard passed through border towns on either side of the divide, crisscrossing the waters as if to stitch lands separated by state politics back together.

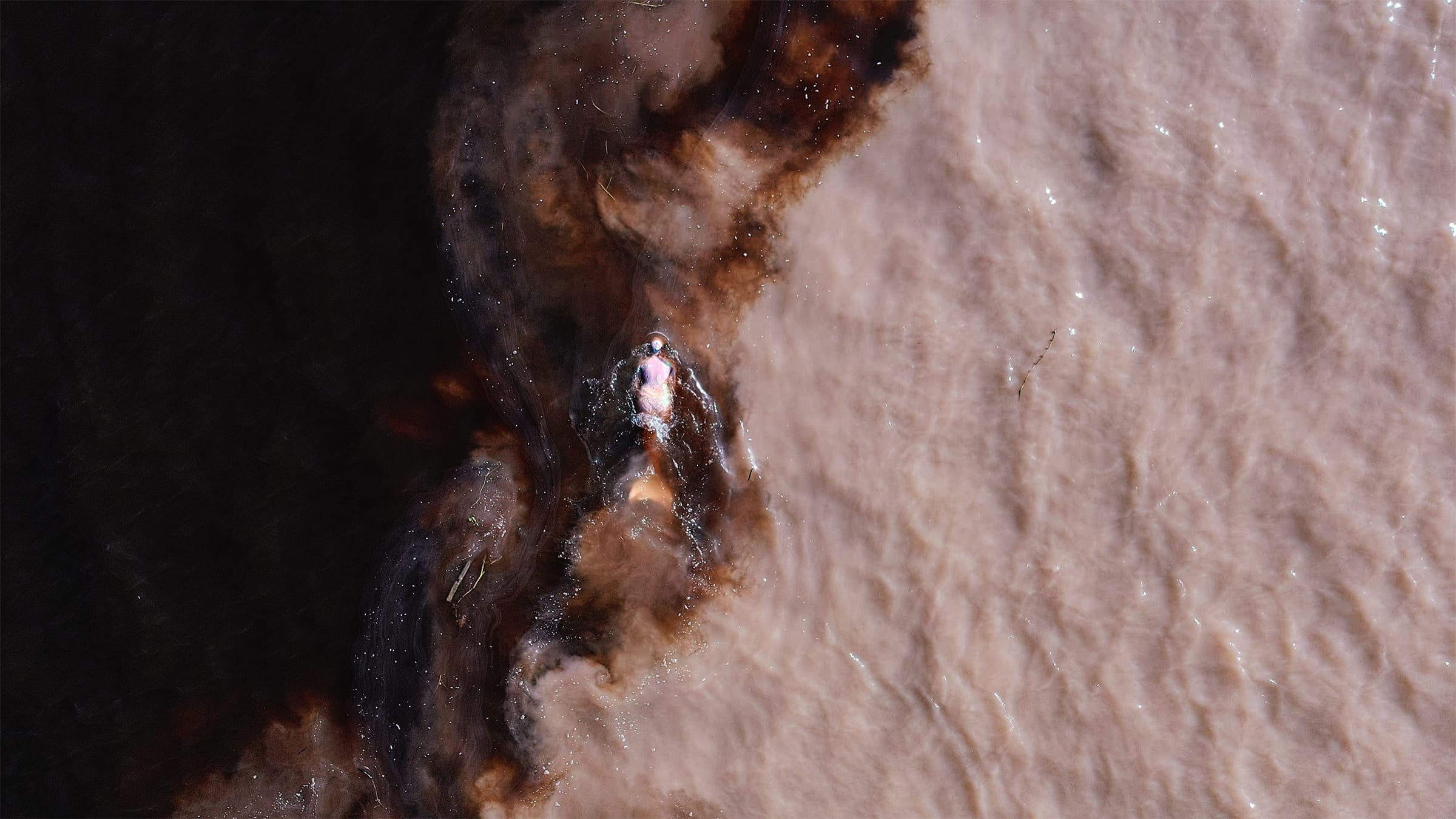

Connection and separation are always movements in the context of a river. Emilija Škarnulytė’s single-channel video installation Æqualia (2023), presented at the 14th Gwangju Biennale in 2023, visualizes that oscillation by following a mermaid swimming between the milk-tea waters of the Rio Solimões and the ink-black currents of the Rio Negro. While Nguyen Trinh Thi’s Ri s̄eīyng (Sound-Less) (2023), a 2023 Thailand Biennale commission, uses a water turbine with sensors, hydrophone, and wi-fi system to collect real-time data of the Mekong River’s waterflow on the Thai-Lao border, to trigger mallets that play a deconstructed ranat ek, a type of Thai xylophone, whose 22 wooden bars are installed within the Haw Kham pavilion in Chiang Rai amid Lanna objects and artifacts.

The associative and galvanizing force of moving water is likewise invoked in Tai Kwun Contemporary’s new exhibition in Hong Kong, ‘Green Snake: women-centred ecologies’, which gathers works by 30 artists and collectives from 20 countries. Among them is Carolina Caycedo, whose video Reciprocal Sacrifice (2022), on view in Wales as part of Artes Mundi 10, tells the story of the Chinook salmon to highlight the struggle to undam – and thus set free – the Snake River that crosses the Pacific Northwest in the US.

The title of ‘Green Snake’ references the eighth-century Chinese folktale Madame White Snake, about demon sisters who have come to symbolize female agency. It also connects the snake’s form with ‘the geomorphology of river systems and the vital energy of the water flowing through them.’ Gidree Bawlee’s animation Lost Shadows (2021), where shadow puppets represent non-human spirits lost to agricultural industrialization, begins with an ancient river’s tales of ‘endless streams’ and ‘fierce flows’ that are now ‘reduced to a sigh.’ While in Adriana Bustos’s Pejerreina (2023), a mud sculpture of a mermaid, whose form resists the fantasies of European explorers, lies in front of a video projection of the Chimiray in Argentina, a tributary of the Uruguay River. A drawing of the Pejerreina mermaid appears on a 10-meter-long map, Afluentes Sudamericanos Carta de navegación (2023), which tracks the rivers of the Americas, from the Putumayo to the Rio de la Plata. Drawings and annotations tell the story of degradation caused by extraction, exploitation, and development through the centuries. Among them is a portrait of a member of the Yanomami, one of the Amazon’s largest Indigenous groups, with the title ‘Genocidio Yanomami 2019’ referring to illegal deforestation and gold mining that intensified under former Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro.

By magnifying rather than containing the multidimensional enmeshment of scales that rivers hold, Afluentes Sudamericanos Carta de navegación is not unlike Fourteen Views. As Lê writes about the military exercises in California that triggered that work’s creation: ‘I recognized that the onslaught I experienced there needed to be amplified rather than wrangled into a rectangle.’ That resistance to square the earth’s circle links back to the fluvial journey that Fourteen Views maps out: of a life propelled by the violent forces of territorial conflict and occupation, which becomes impossible to contain. In ‘Green Snake’, Seba Calfuqueo’s single-channel video performance Tray Tray Ko (2020), embodies that resistance. A stream of electric blue fabric trails the artist as they follow the Rio Palguin in Chile. When Calfuqueo reaches a trayenko, the Mapuche name for a waterfall, they disappear into the cascade, becoming one with the flow.

‘Green Snake: women-centred ecologies’, curated by Kathryn Weir and Xue Tan, is on view at Tai Kwun Contemporary, Hong Kong, from 20 December 2023 to 1 April 2024.

Stephanie Bailey is Art Basel’s Conversations Curator, Art Basel Hong Kong, as well as the Art Basel Content Advisor and Editor, Asia.

Published courtesy of Art Basel.

Leave a Reply