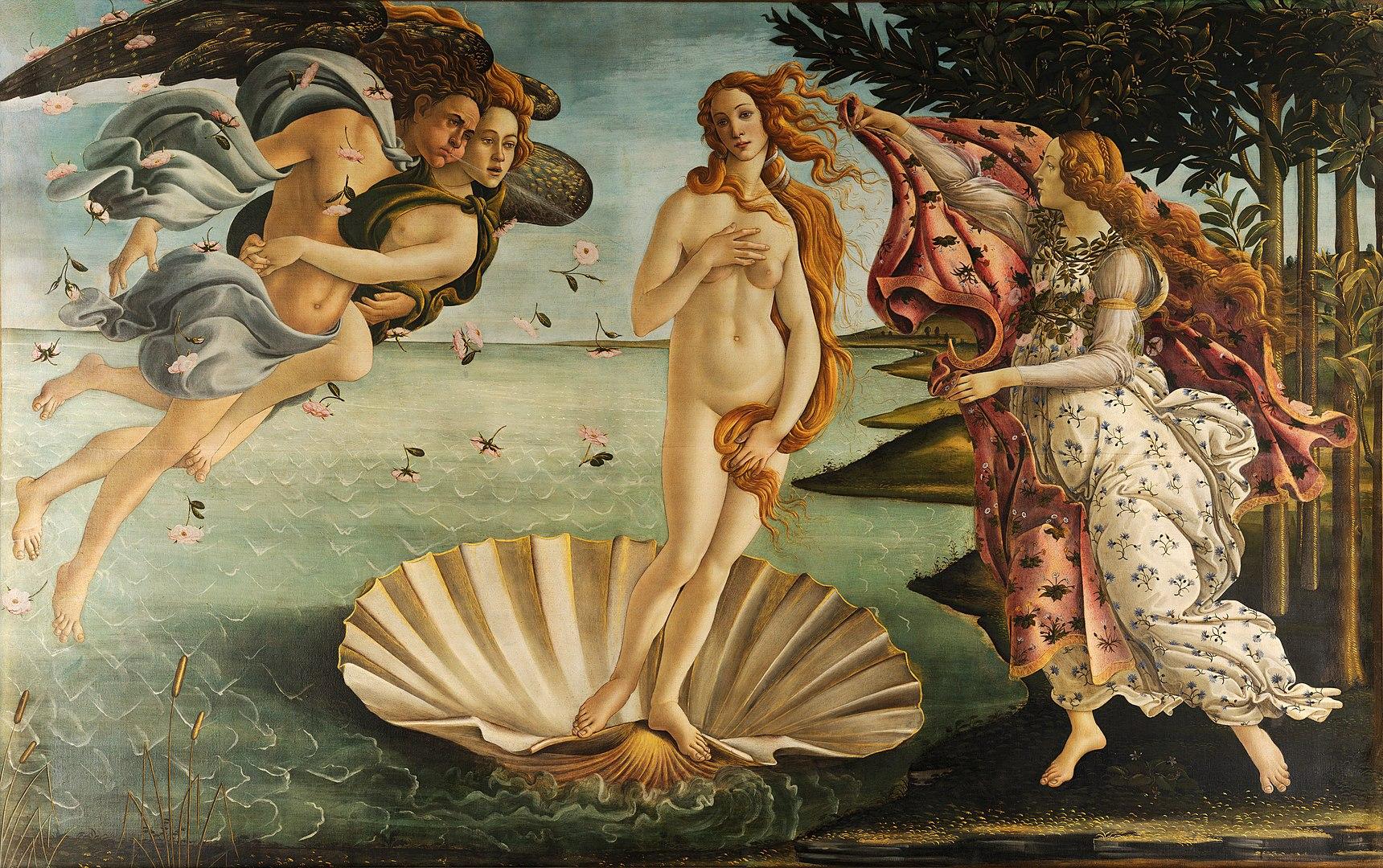

Sando Botticelli’s Primavera, or Allegory of Spring, painted in the late fifteenth century, is one of the most admired, yet controversial, paintings in the world. A perennial celebration of the most vibrant season, it evokes the spirit of spring through its depictions of figures from classical mythology. Standing in a grove, from left to right, we can see Mercury, whom we recognize from his winged sandals; The Three Graces; Venus as the mistress of her domain; Flora, who is scattering flowers all around; and Chloris in the act of being ravished by Zephyrus (their union will transform her into Flora). Cupid, meanwhile, hovers above Venus.

The painting, while pleasant to look at, conceals a complex meaning that, even to this day, scholars are still not in agreement about. Daniela Parenti, the curator of the medieval and early-Renaissance art at the Uffizi Gallery in Florence, walked us through these fun and enlightening facts about Allegory of Spring.

1. The characters in the painting were only identified in the late 19th century

While Botticelli was fairly popular and revered during his lifetime, he fell out of favor in the following century. With the exception of sporadic mention in art history texts from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, he was mostly forgotten up until the second half of the nineteenth century. Giorgio Vasari, in his biography of Botticelli, whom he looked down on, recalls a painting hanging at the Villa Castello matching Allegory of Spring, and described it together with the Birth of Venus. It was only exposed to the public at the Galleries of the Academy in 1853, and was moved to the Uffizi Gallery in 1919.

After the public could finally appraise the painting firsthand, came the attempts to identify the characters. Adolf Gaspary, who was a philologist well-versed in Renaissance literature and not an art critic, first saw a link between Botticelli’s Allegory of Spring and a poem by Agnolo Poliziano titled “Rusticus,” which celebrated country life and the renewal of seasons.

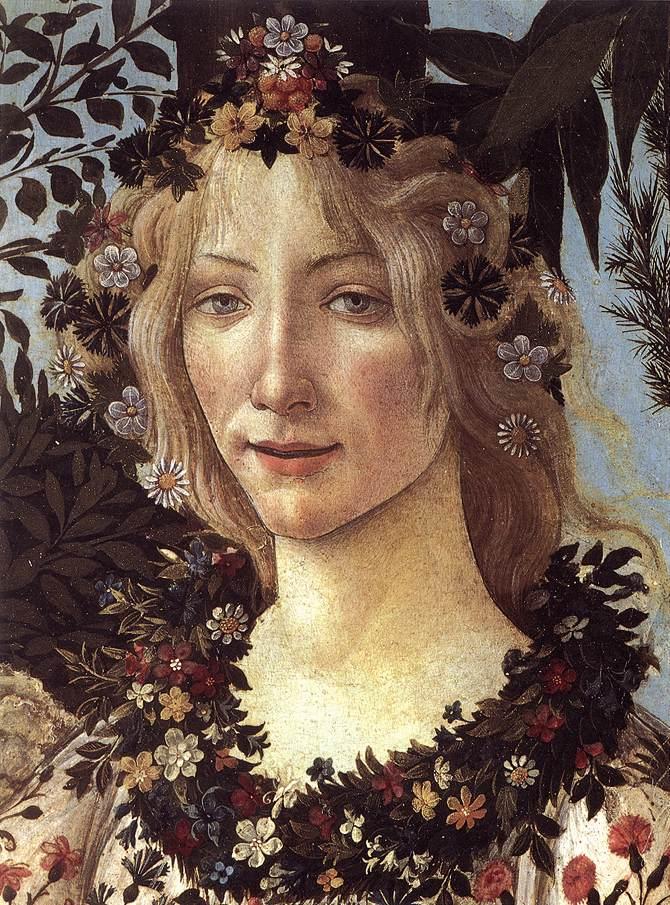

2. Botticelli painted many facets of Venus

In Botticelli’s Allegory of Spring, Venus is the mistress of her domain and is wearing regal garb while dispensing love, harmony, and the regenerative power of nature. She wears a blue gown and a red drape, the same colors worn by the Virgin Mary, but reversed.

By contrast, in The Birth of Venus, he drew inspiration from Greco-Roman statuary depicting Venus in the nude, whether in the act of covering herself in a sign of modesty or as part of anadyomene, which means “rising from the sea.” He also follows the mythical narrative that nymphs dressed Venus after she reached the shores of Cyprus.

In Venus and Mars, which portrays the two deities reclining, he reaches a happy medium: while her gown is regal and intricate, to the point that her braids become indistinguishable from her jewelry, it is draped in a way that showcases her curves, and the bare foot that peeks from the gown suggests her sensuality.

3. Allegory of Spring seems to defy 15th-century perspective

In a century where painters were striving to recreate three dimensions in their paintings, Botticelli notoriously disliked landscape paintings, and even his Birth of Venus does not take rules of perspective into account, as he preferred focusing on his characters rather than the overall environment. In the case of Allegory of Spring, putting them all side by side, with little regard to the dimension of space, allowing for a clearer reading and interpretation of the painting.

4. Flowers are both decorative and meaningful

In the painting, trees are in bloom, the grass is covered in blossoms, and Flora is strewing flowers from her lap. There are around 138 different plants in the painting, including roses, forget-me-nots, irises, ranunculi, carnations, fleurs-de-lys, poppies, daisies, pansies, and jasmine blossoms. It is a celebration of the bounty of nature, but these flowers indicate more than the renewal of seasons:

their meaning can vary based on whether they’re placed in a pagan or a Christian context.

Carnations, daisies, and jasmine blossoms are symbolic of love and matrimony; poppies represent prosperity and fertility; there’s also hellebore, said to be the harbinger of eternal youth, which can also heal the insanity brought about by unrequited love. Oranges and orange blossoms, which we see in the trees of the grove, symbolized matrimony too, as Juno offered them to Jupiter as marriage dowry.

5. Allegory of Spring has philosophical undertones

Regardless of the actual meaning of the painting, scholars agree that there is a Neoplatonic component of Allegory of Spring. The Neoplatonic philosophy had a strong following in fifteenth-century Florence because it reconciled classical antiquity with Christianity. Those who adhered to it believed that contemplating beauty aroused a feeling of love that would make one closer to God. While it’s unclear how familiar Botticelli was with the religious philosophy, the subjects of his paintings have an abstract and idealized beauty and were thus highly favored by followers of Neoplatonism.

Leave a Reply