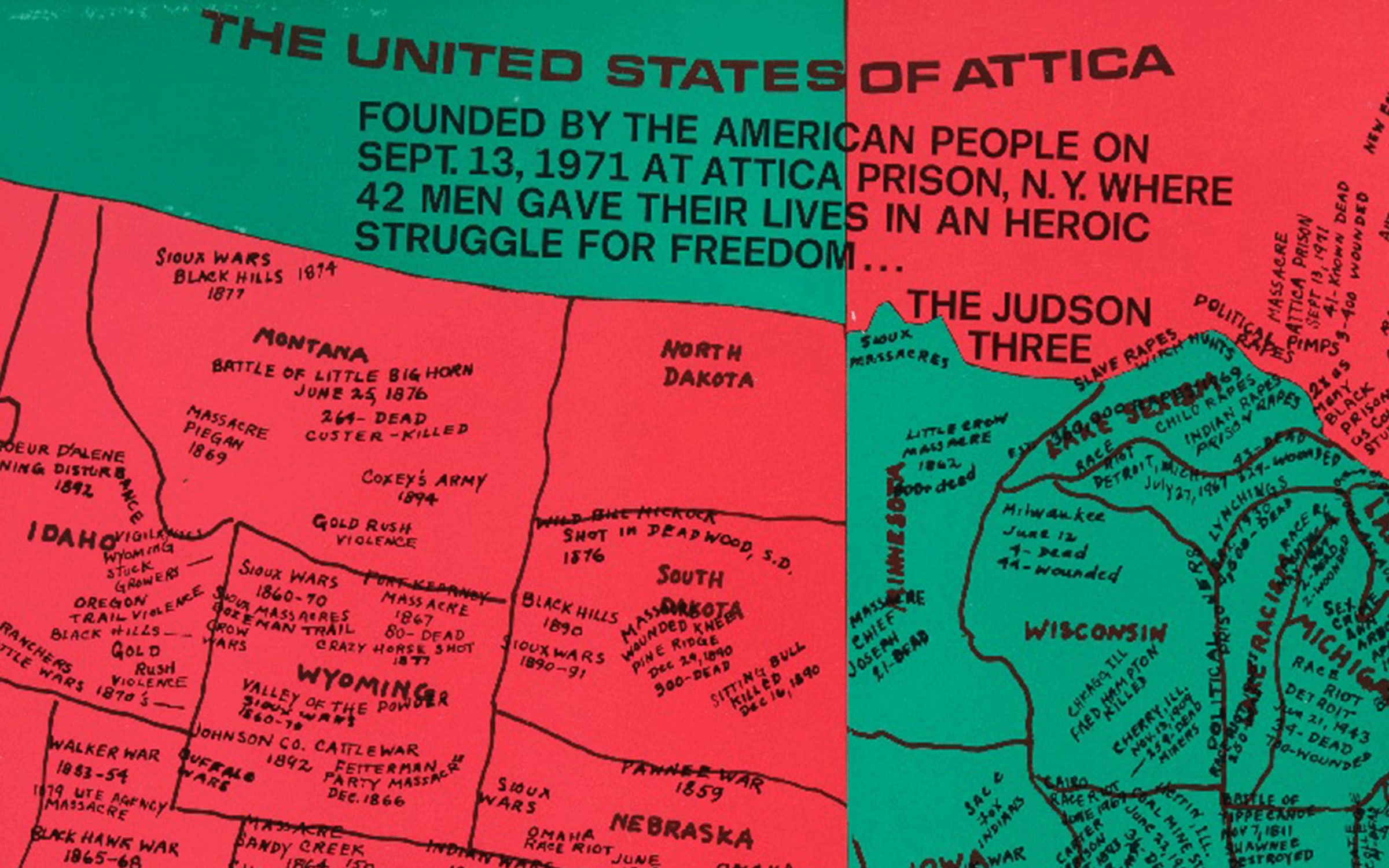

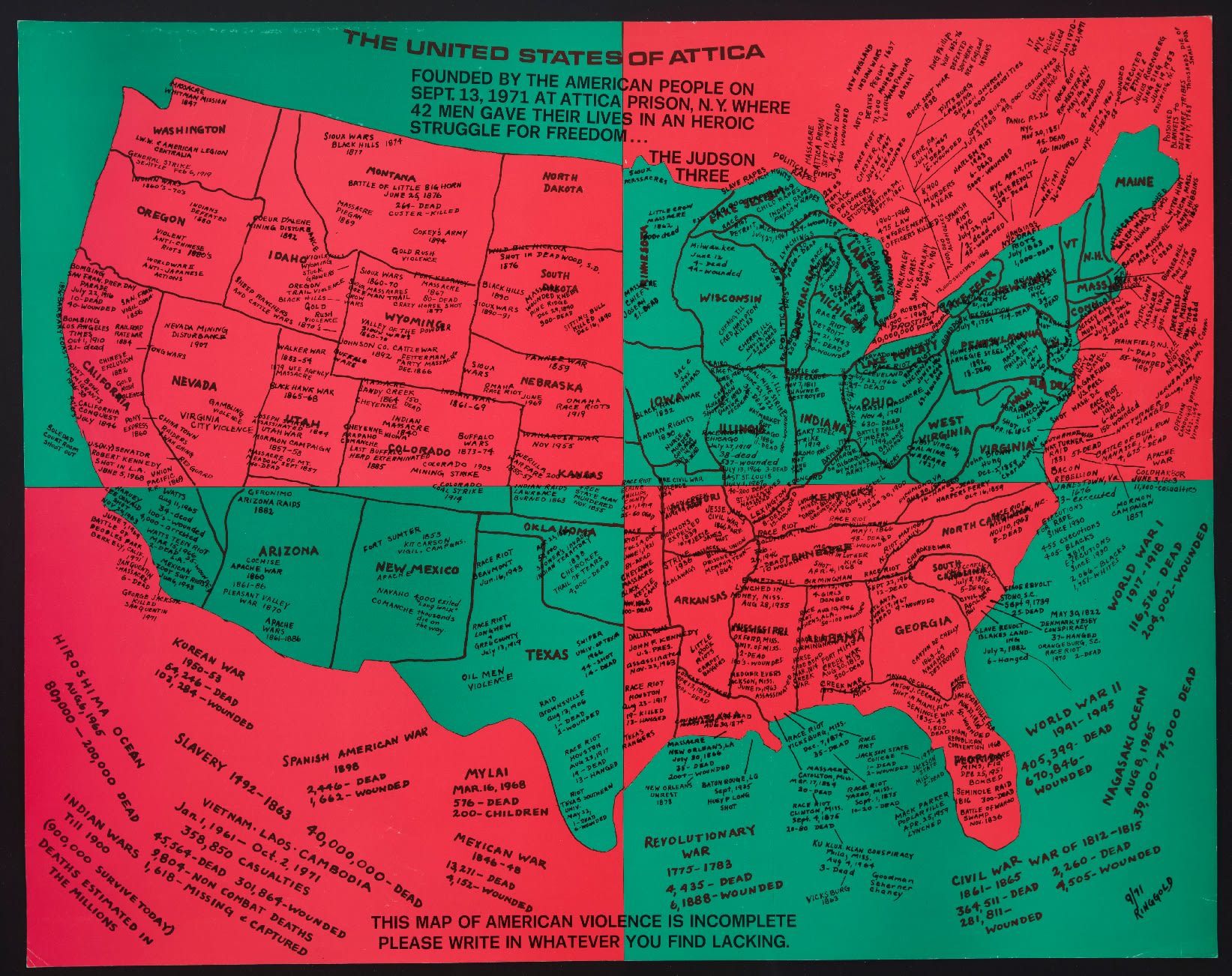

In her painting United States of Attica (1972), the artist Faith Ringgold presents the familiar American map in a new light. It is darkened and covered with a jumble of texts that give it a confused appearance – a confusion heightened by the solid blocks of red and green supported by black lines, reminiscent of the Pan-African flag. The inscriptions catalog violent acts committed against Black and indigenous people in the United States since the 18th century. There are so many that the work approaches illegibility.

The painting’s title refers to a historical revolt – the Attica prison uprising – which Ringgold calls ‘a heroic struggle for freedom’. In 1971, the inmates of the prison in New York State opposed the cruel conditions of their detention; they took control of the prison and took hostages. Although the prisoners engaged in negotiations, the American government put a brutal end to the insurrection by sending in armed forces. The result: 43 dead. It was a massacre.

With this tragic episode, the American state once again reproduced the aggressive pattern that constitutes its existence. Attica is the product of a mold that has been cast time and again. It is the allegory of a country that is an open-air prison for those whose rights are trampled day after day. The adjective ‘united’ in its name is undermined by the revelation of its profound disunity.

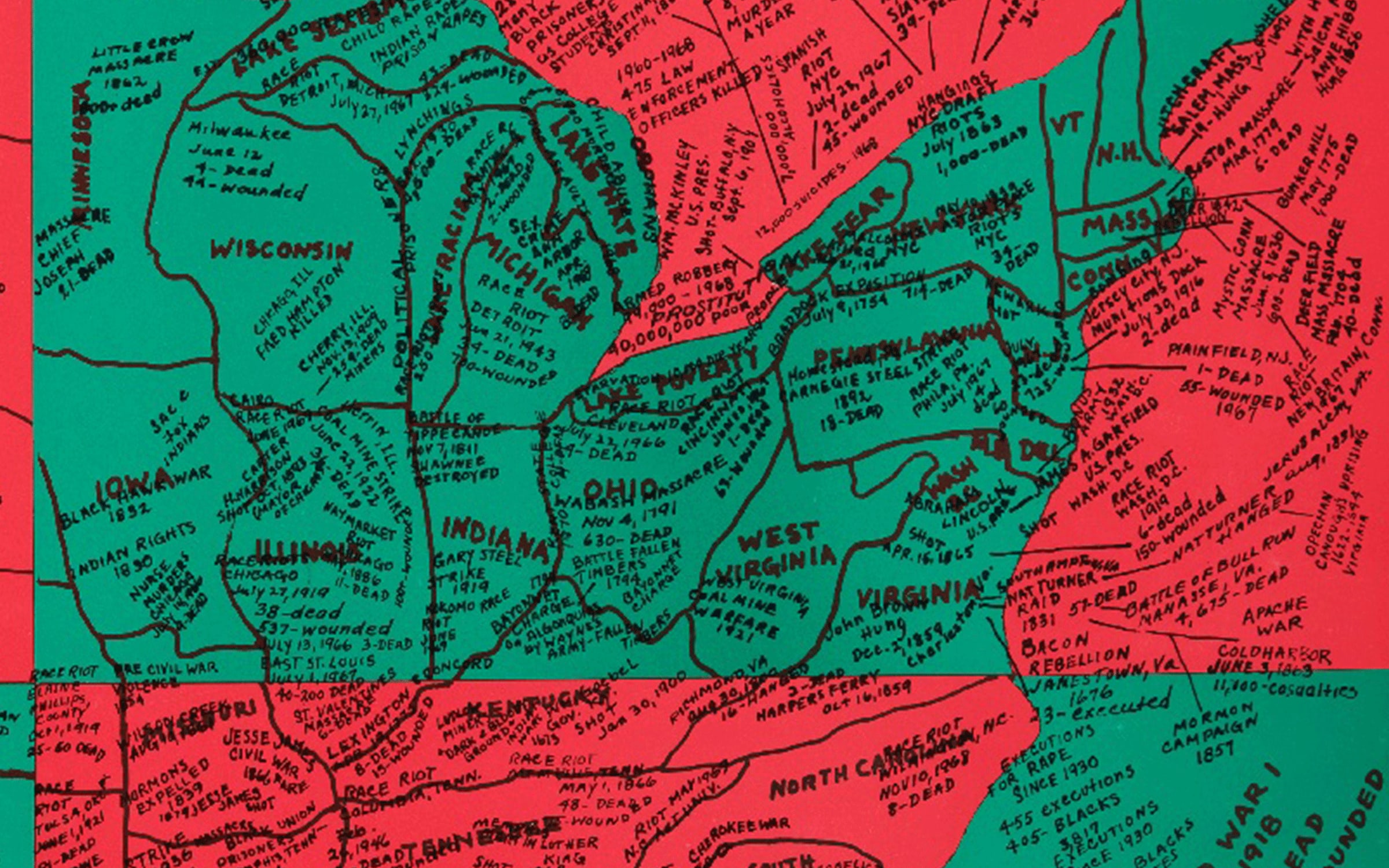

The rectilinear shape of the drawings of different states contrasts with the almost scrawled writings. These writings squeeze themselves in where they can and defy a geographical order that poorly masks the events they name. And thus, we come to understand the absurdity of the linear order that divides one state from another, and which took bloody violence to impose it. The Indigenous peoples swept away by the colonists’ genocidal brutality have never stopped their opposition. Faith Ringgold mentions them several times, recalling revolts by the Navajo, the Comanche, and the Apache – the last of whom appear through the figure of Geronimo, who fought for the rights of First Nations peoples.

The African men and women extracted by the millions to feed the capitalist machine, as well as their descendants, also appear many times. Ringgold’s painting makes references to the four schoolgirls killed by a church bombing in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, to the Black Panther activist Fred Hampton murdered by police in 1969, and to numerous rebellions undertaken by victims of slavery and racial discrimination. Immigrants – constantly rejected in the country – appear through mentions of bullying and harassment suffered especially by Chinese populations.

The inclusion of ‘political rapes’, which refer to the sexual assaults suffered by enslaved women for centuries, reverberates with the visceral feminism of Faith Ringgold’s work. The armed conflicts undertaken by the United States to expand its borders, such as the Mexican-American War in the 19th century, likewise feature in this unprecedented map of the country.

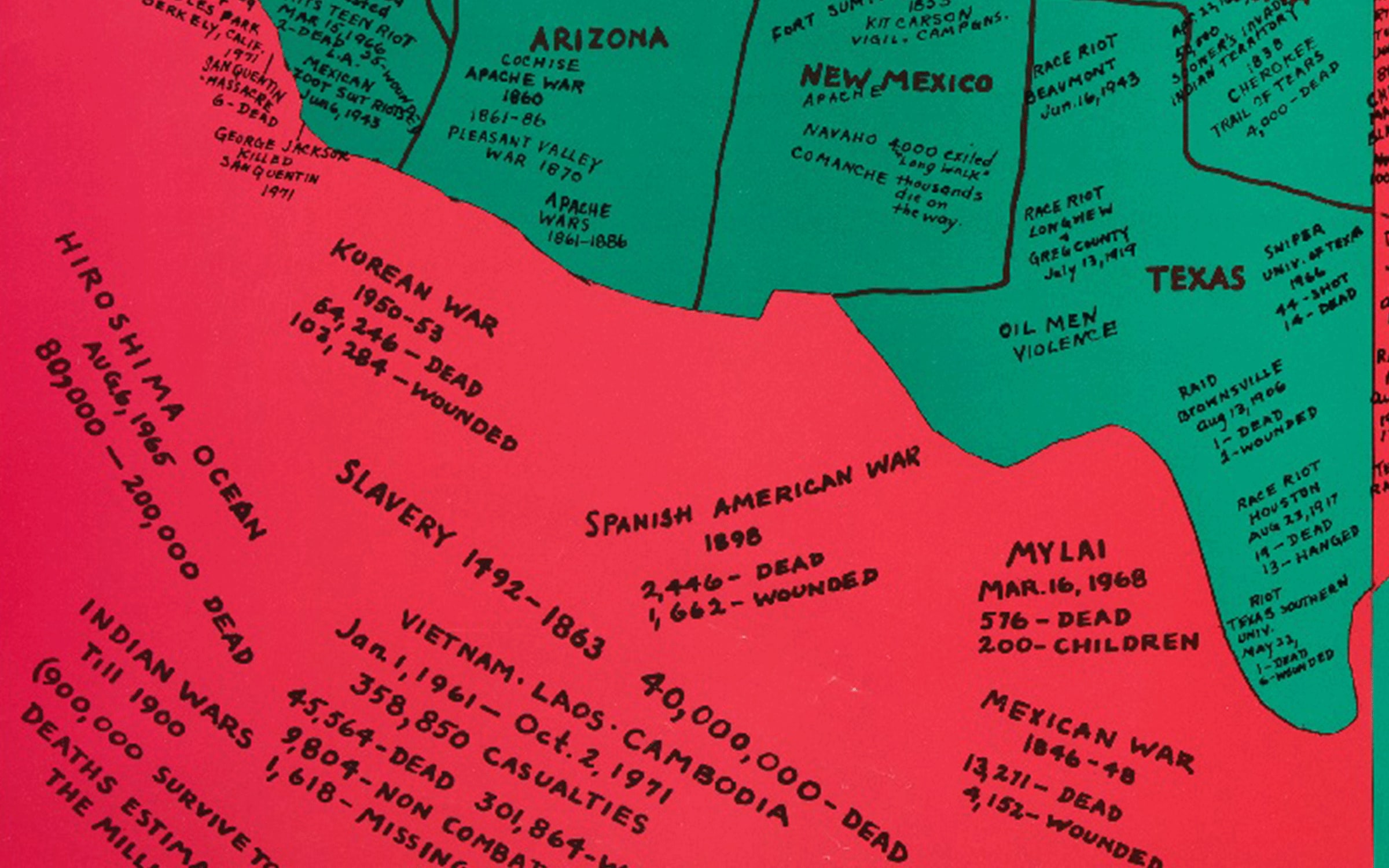

The list of crimes committed in the name of the American ideal is so long that it extends beyond its own borders, both figuratively (in the painting) and literally. Ringgold illustrates and underscores the international scope of the nation’s aggressions, from the nuclear bomb dropped on the Japanese city of Hiroshima to the Korean and the Vietnam wars.

Ringgold paints a scholarly picture of systemic violence that is consubstantial with the existence of the United States, whose historical starting point contrasts starkly with its proclaimed ideals. The country’s history is splattered with blood, and the appearance of its misdeeds, at times juxtaposed in a twisted manner, makes contemplation of the map a dizzying experience. We cannot tell where the brutality began, nor where (and if) it ends.

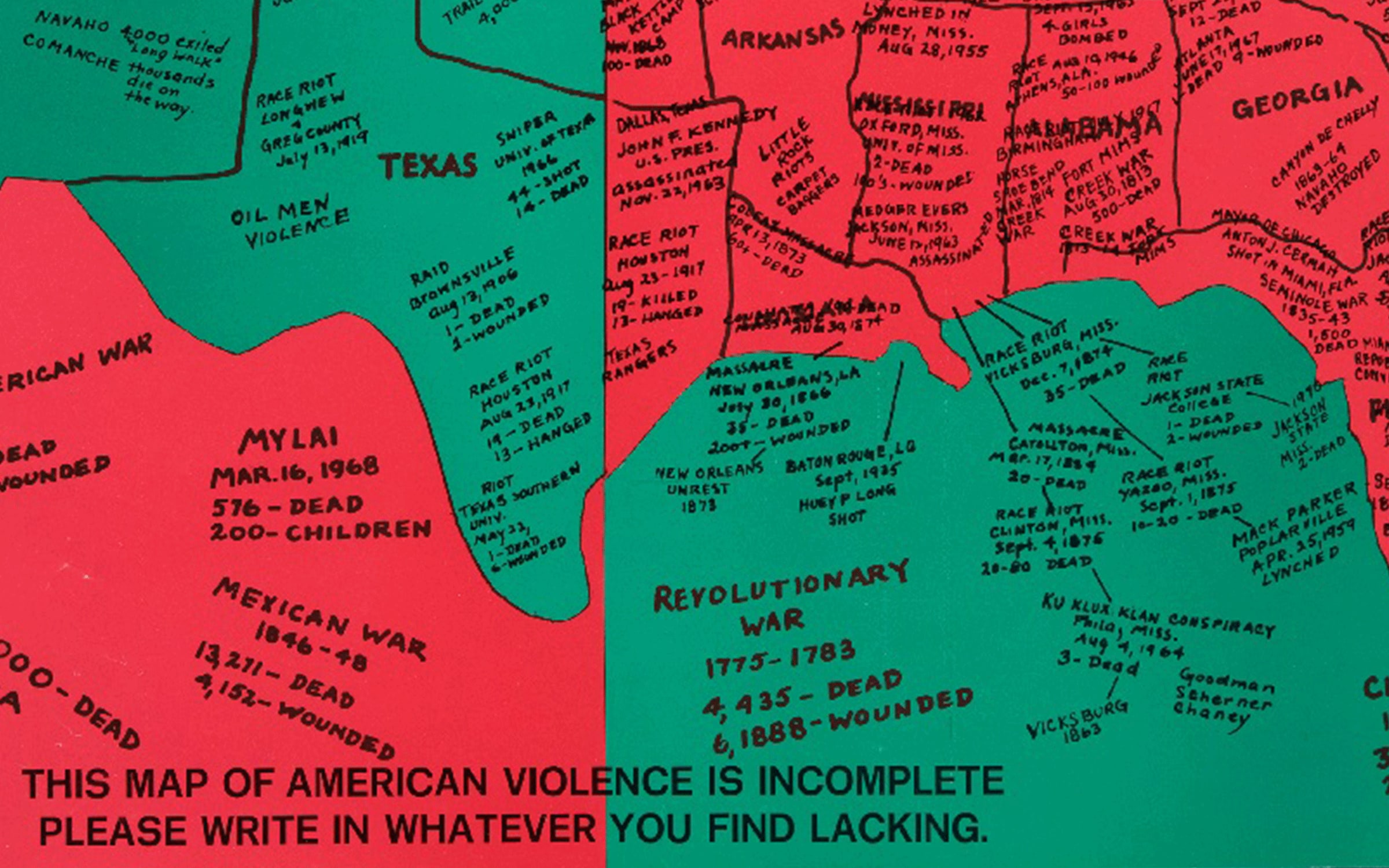

The artist’s caption at the bottom of painting reads, ‘this map of American violence is incomplete, please write in whatever you find lacking.’ Fifty years later, and we hardly know where to find the space to do so.

‘Faith Ringgold. Black is beautiful’

Until July 3, 2023

Musée national Picasso-Paris

Rokhaya Diallo is an award-winning journalist, author, and director based in Paris.

English translation: Jacob Bromberg.

Published on January 30, 2023.

Leave a Reply