The government-commissioned Farmer Review warned in 2016 that the UK construction industry was “facing challenges that have not been seen before”. In no uncertain terms, it called for major industry-wide change. The “overwhelming risks” foreseen in the review sadly seem to have come to pass.

Major contractor Carillion’s collapse comes shortly after an autumn in which UK construction activity fell at its fastest pace in five years. Studies have found that Brexit could cost the industry £10 billion, while the 2017 government industrial strategy was widely denounced as inadequate to generate real change.

Of the many issues Farmer highlighted, the industry’s resistance to modernisation, along with the “ticking time bomb” that is the ever-widening skills shortage, stand out. The government’s Working Futures report into the future of the country’s labour market predicts hundreds of thousands of vacancies in skilled technical, professional and managerial roles by the early 2020s. One obvious solution is to increase the number of women in the construction industry.

The worst gender balance

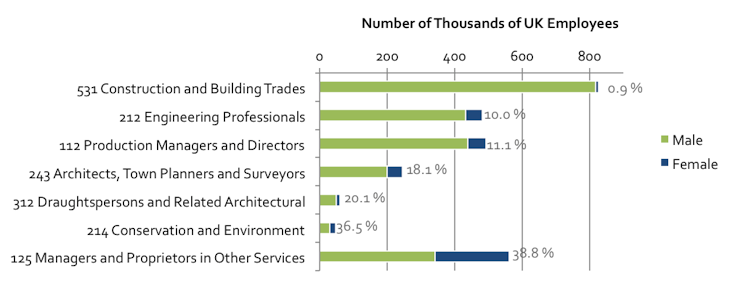

The construction sector has the worst gender balance of any, with the UK lagging behind the rest of Europe. Less than 1% of its 800,000 construction and building trades workers are women, and even when you add architects, planners and surveyors it only rises to 18%:

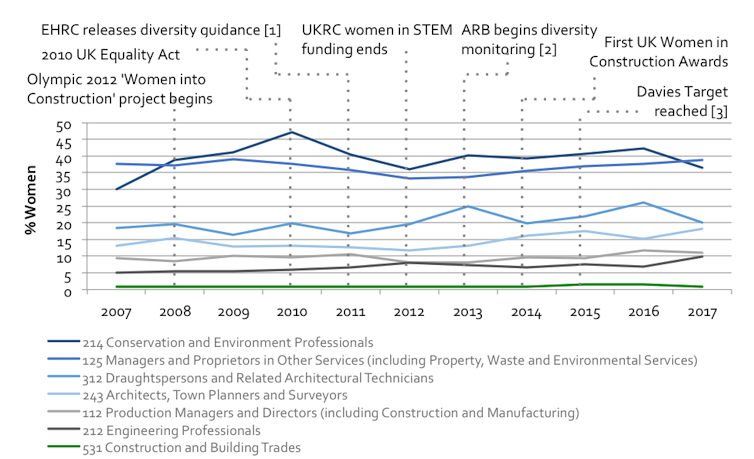

Of course, both industry and government have considered this issue. But attempts as far back as the WISE campaign of the 1980s to encourage more girls to consider careers in construction just haven’t worked. While more women are entering the sector, they are leaving just as quickly. The net result is that numbers of women in construction roles have remained more or less static for at least a decade:

Dillon and Moncaster

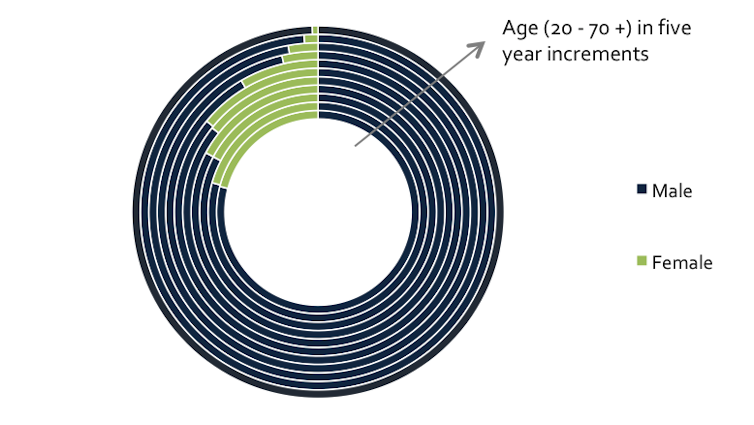

The blame is repeatedly levied at parents, teachers and careers advisers, and women having children. While the data is simply unavailable for women in the building trades, recent Department for Education figures suggest an alternative reason. Just five years after graduation, long before starting a family, women engineers and architects are already being paid less than their male counterparts.

The lack of career progression that this suggests increases with age, with the number of women in senior positions dwindling to a miniscule proportion. With such inequality of pay, matched by inequality of treatment, it is no wonder they don’t stay.

Bad for women, bad for business

A group of senior industry women believe that not only is this bad for women, it is bad for business. They set up the Equilibrium Network, which funded some of our research looking into whether having women in senior positions boosts business financial performance.

We started by analysing major international and cross-industry studies, all of which indicate that there is a clear correlation between a greater number of women on boards and company financial performance. We then looked in the academic literature for evidence of causation, in order to predict whether this trend might hold true for the construction sector.

We found three explanations to suggest this is the case. First, having more women on the boards of companies improves the operation of the boards themselves. They provide a greater range of perspectives and insights, more closely representing companies’ demographically diverse stakeholders, as well as improving collaborative teamwork.

Second, having women at senior levels reduces the leaky pipeline lower down companies. Senior women provide role models and mentoring, and a more positive working environment. Also, they are more likely to promote other women, as they are more likely to recognise their skills.

All of these lead to better retention and satisfaction of skilled employees for the company. Diverse teams have also been repeatedly shown to be better performing and more innovative, and so having more women at all levels is also good for team performance.

Finally, better gender diversity at board level improves the image of companies – with both the public and with investors. This helps to boost sales and market performance. As the construction sector suffers from an extremely poor public image, we believe this impact would be particularly positive for construction firms.

Our study also revealed an acute lack of gender data specific to the construction sector. It was based instead on large studies that crossed different sectors and smaller academic studies of a few niche areas or individual companies. This absence of any measurement of gender inequality can only have contributed to the lack of progress in this area.

![]() The new president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Robert Mair, used his inaugural speech to call on his profession to transform infrastructure and transform lives. It is a statement for which the Carillion crisis serves as a violent example. Our research suggests that in order to do this we first need to transform our outdated industry. Promoting women to senior levels is essential for this to happen.

The new president of the Institution of Civil Engineers, Robert Mair, used his inaugural speech to call on his profession to transform infrastructure and transform lives. It is a statement for which the Carillion crisis serves as a violent example. Our research suggests that in order to do this we first need to transform our outdated industry. Promoting women to senior levels is essential for this to happen.

Alice Moncaster, Senior Lecturer in Engineering, The Open University and Martha Dillon, PhD Candidate in Engineering, University of Cambridge

This article was originally published on The Conversation.

Leave a Reply