The world feels heavy again. Politics seethes with bitterness. Civil liberties bend under pressure. Wars erupt in places that once seemed far away but now echo through our daily lives. The news scrolls endlessly across our screens, a litany of anxiety and outrage. Even those who try to keep perspective sense a low hum of exhaustion running beneath it all. In such moments, laughter can seem almost obscene. Who dares to joke while the world burns? Yet perhaps the better question is: how can we not?

Throughout history, humor has been one of humanity’s most reliable tools for survival. In times of chaos and despair, laughter has offered more than comfort. It has provided a way to endure, to resist, and to reimagine. It has allowed people not only to survive turmoil but to find meaning within it. When societies have stumbled toward darkness, humor has often been the faint, defiant light that refused to go out.

In the mud-soaked trenches of the First World War, soldiers passed around what were called “trench journals.” These were small, homemade publications filled with jokes, cartoons, and biting parodies of military life. They were written by men who might not live to see another dawn. Yet in their humor there was fierce vitality. A soldier who could laugh at his commanding officer’s incompetence, or at the absurd bureaucracy that governed his daily misery, was a soldier who had reclaimed a measure of control. The laughter was not escapism; it was rebellion against despair.

On the home front, humor took on a different tone. Cartoons in British and French newspapers mocked rationing, bureaucracy, and even the government’s endless propaganda. It was a shared language between civilians and soldiers, a way of saying: we see the absurdity of this, and still we carry on. The laughter bound them together across distance and terror.

By the Second World War, Britain had institutionalized humor as a national defense. Radio programs offered wry commentary on the war’s hardships. Jokes about Hitler’s ridiculous mustache or the blundering Luftwaffe circulated even during the Blitz. The laughter that rippled through shelters as bombs fell overhead was a strange kind of prayer, not for deliverance but for dignity. It said, simply, that the human spirit would not be cowed.

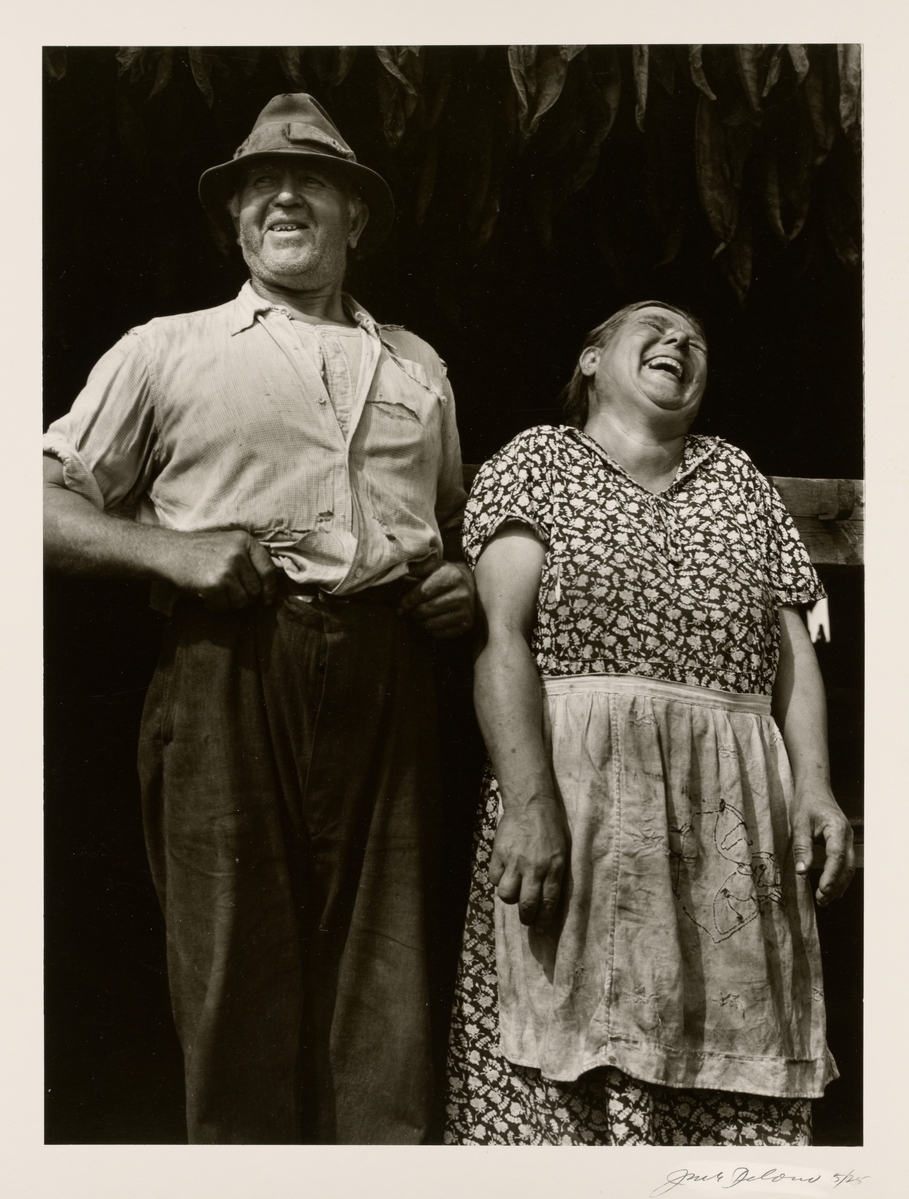

Original public domain image from Statens Museum for Kunst

Authoritarian regimes have always recognized humor’s subversive power. In the Soviet Union, “Radio Yerevan” jokes, short, sardonic question-and-answer routines, circulated in whispers. They mocked the absurdities of daily life under communism, the empty promises of the state, the gap between propaganda and reality. “Is it true,” one joke asked, “that there is freedom of speech in the Soviet Union, just like in the United States?” The answer: “Yes. In the United States, you can stand in front of the White House and shout ‘Down with Reagan!’ In Moscow, you can stand in front of the Kremlin and shout ‘Down with Reagan!’”

Such jokes did not topple governments, but they punctured the illusion of omnipotence on which tyranny depends. They reminded people that others saw what they saw, that the lie was not complete. In 1980s Poland, the Orange Alternative movement took this idea to the streets. Protesters dressed as elves and gnomes, carrying absurd banners, staging comical demonstrations. When police arrested them, the state looked ridiculous. The laughter turned oppression into farce.

Even in the aftermath of catastrophe, humor has helped survivors make sense of the senseless. After genocide and civil war, people often turn to dark humor as a way of reclaiming power over memory. A grim joke about loss or suffering can mark a step toward healing. To laugh at what once terrified you is not to dismiss it but to declare that it no longer owns you. Psychologists studying post-conflict societies have found that laughter helps transform trauma into narrative, and narrative into endurance.

What all these moments share is the recognition that humor is not trivial. It is a method of survival that works through recognition rather than denial. It allows people to confront what is unbearable and make it bearable for one more day. It is an act of seeing clearly and still choosing to smile.

Original public domain image from Getty Museum

Today, the circumstances are different but the need is the same. We live in an age of endless crisis: political polarization, ecological dread, a wariness toward institutions that once promised stability. The constant noise of information leaves us raw and reactive. Humor, in this context, is not frivolous. It is a pressure valve, a way to process the absurdities of a world that often feels beyond comprehension.

When political satire skewers hypocrisy or lays bare the contradictions of public life, it performs a civic function. It reminds us that power can be mocked, that authority is not sacred. The laughter that follows is not merely personal relief but a quiet act of democratic renewal. Comedy, at its best, restores proportion. It tells us that the emperor, once again, has no clothes.

But laughter is more than critique. It also builds connection. Shared humor creates a kind of common ground that politics rarely manages. A joke, when told with generosity, can make people who disagree see themselves in one another, if only for a moment. In that shared spark of recognition lies the seed of empathy. In times of fragmentation, this may be the most radical gift of all.

It is easy to forget that humor also cultivates creativity. Every good joke depends on surprise, on seeing the world from an unexpected angle. That same agility of thought is what allows societies to adapt in moments of upheaval. A culture that can laugh is a culture that can still imagine alternatives. The creative spark that drives art and innovation is kindred to the one that drives humor: both depend on a willingness to look at the familiar and see something new.

For these reasons, we should treat humor not as a distraction from civic life but as an essential part of it. It is as vital to a healthy democracy as dissent or debate. A society that can laugh at itself is one that has not yet succumbed to fear. But humor can also go astray. When it turns cynical or cruel, it ceases to connect and begins to corrode. The challenge for our era is to nurture humor that enlightens rather than inflames, that lifts rather than belittles.

Comedy that punches up instead of down, that mocks arrogance and hypocrisy without dehumanizing, becomes a form of moral clarity. It exposes our follies without losing faith in our capacity to change. It allows us to imagine a better version of ourselves precisely because it refuses to take the current one too seriously.

We can see glimmers of this in the present. Comedians who address race, gender, or inequality with empathy as well as irony open space for conversations that politics alone cannot. Improvisational theater groups bring together people from different backgrounds to laugh at their shared awkwardness, building community through play. Even in protest movements, laughter often stands alongside outrage. Dancing, singing, and joking in the streets do not trivialize injustice. They reclaim the joy that oppression tries to erase.

What the satirists of ancient Rome, the cartoonists of wartime Britain, and the jesters of post-communist Europe all understood is that humor is not the opposite of seriousness. It is its necessary companion. To laugh is not to look away from pain, but to insist that pain will not have the final word.

We need that insistence now. The temptation, in an age of perpetual crisis, is to become grim, to let anxiety ossify into fatalism. But humor keeps us fluid. It reminds us that history has always been chaotic, that human folly has always bordered on farce, and that somehow, we have always stumbled through. It offers perspective, which is the first step toward resilience.

If society is a ship in stormy seas, policy and reason may be its sails and rudder, but humor is its buoyancy. Without it, the vessel moves forward, yet risks sinking under its own solemn weight. Laughter keeps us afloat long enough to find calmer waters.

So yes, the world feels in turmoil. But we have been here before. We have laughed through worse and rebuilt afterward. The joke, if we are wise enough to tell it, is not that everything is falling apart, but that we still have the audacity to find joy amid the collapse.

To laugh, in times like these, is to assert our humanity. It is to say, as generations before us have said in bomb shelters and bread lines, in censored theaters and crowded squares: We are still here. We still see. And we can still laugh.

That laughter may not change the world overnight. But it just might keep it alive long enough for us to change it ourselves.

– S&P

Leave a Reply