As soon as you step foot in the gallery, you’re transported back in time, back to the Postwar period in the Paris neighborhood of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, surrounded by the era’s best artists. Nicolas De Staël, Jean Dubuffet, Victor Brauner, and Jean Fautrier can all be found at Applicat-Prazan. It’s a two-part time capsule, with one outpost on Rue de Seine and, since 2010, another on Avenue Matignon. For 30 years, the gallery has been a reference point for lovers of the Nouvelle École de Paris, bringing together artists from the years surrounding the Second World War and combining realist figurative trends with abstract pictorial expression.

‘This label works for us in terms of branding, but it’s a label that encompasses very different realities,’ explains Franck Prazan, the gallery’s owner. ‘I prefer talking about Postwar painters.’ He focuses on about 30 of the 350 painters that currently make up the market.

Franck Prazan bought the gallery from his father Bernard Prazan 18 years ago. ‘During the Second World War, my father was a child and was in hiding. He didn’t go to school and he started work at the age of 15 as a textile mechanic.’ He didn’t work in a garage, but in Parisian couture workshops: His job was to attach sleeves to blazers. ‘Very early on, he became passionate about contemporary art, and developed his own sense of culture by visiting the museums and art galleries that were already springing up in the area.’

After first working in the textiles industry, Bernard Prazan returned to his first love and in 1989, he opened a gallery on Rue Guénégaud in the 6th arrondissement. Unfortunately, the market plummeted a short time afterwards because of the Gulf War and there was an economic slump. The first gallery had to close; Bernard Prazan opened another one on the Rue de Seine, under the name Applicat. ‘It was a brand name that belonged to him. It encapsulates the idea of paying attention to what one does and also has the merit of being at the beginning of the alphabet. At art fairs, we are always at the top of the list.’ Later, he added his surname, giving birth to Applicat-Prazan. It was a difficult beginning. ‘With the crisis in the 1990s, prices fell so low that it was a good 10 years before the market started to become favorable again,’ remembers Franck Prazan.

After going to business school, Franck Prazan took on a series of jobs in the luxury industry, at Dior, Le Bon Marché, and Cartier. He started to collect art. But was it the artists that his father liked so much? No! ‘Martin Barré’ – minimal radical. What else? ‘Barré, Barré, Barré. But only between 1954 and 1960. He was collected a lot by artists and curators, and they’re usually the last people to sell. But over the years, I’ve managed to build up a large collection of the works illustrated in Michel Ragon’s monograph Martin Barré et la poétique de l’espace, which was published alongside the exhibition at the Galerie Arnaud in 1960.’ This just about sums up Prazan’s character.

Christie’s contacted him in 1996, when it decided to build a presence in the French market. ‘I was interested in the idea of starting almost from scratch. I had to find a space, recruit staff, build the logistical framework. An auction house is a factory in the center of the city.’ Mission accomplished. But his father fell ill in 2004 and without hesitation, he bought the gallery from him. He had inherited his father’s passion. ‘As a child, I rarely saw my father, who worked a lot. But every Sunday and for every vacation, we would go to museums together. The history of Modern art became an almost atavistic knowledge for me, like a second language.’

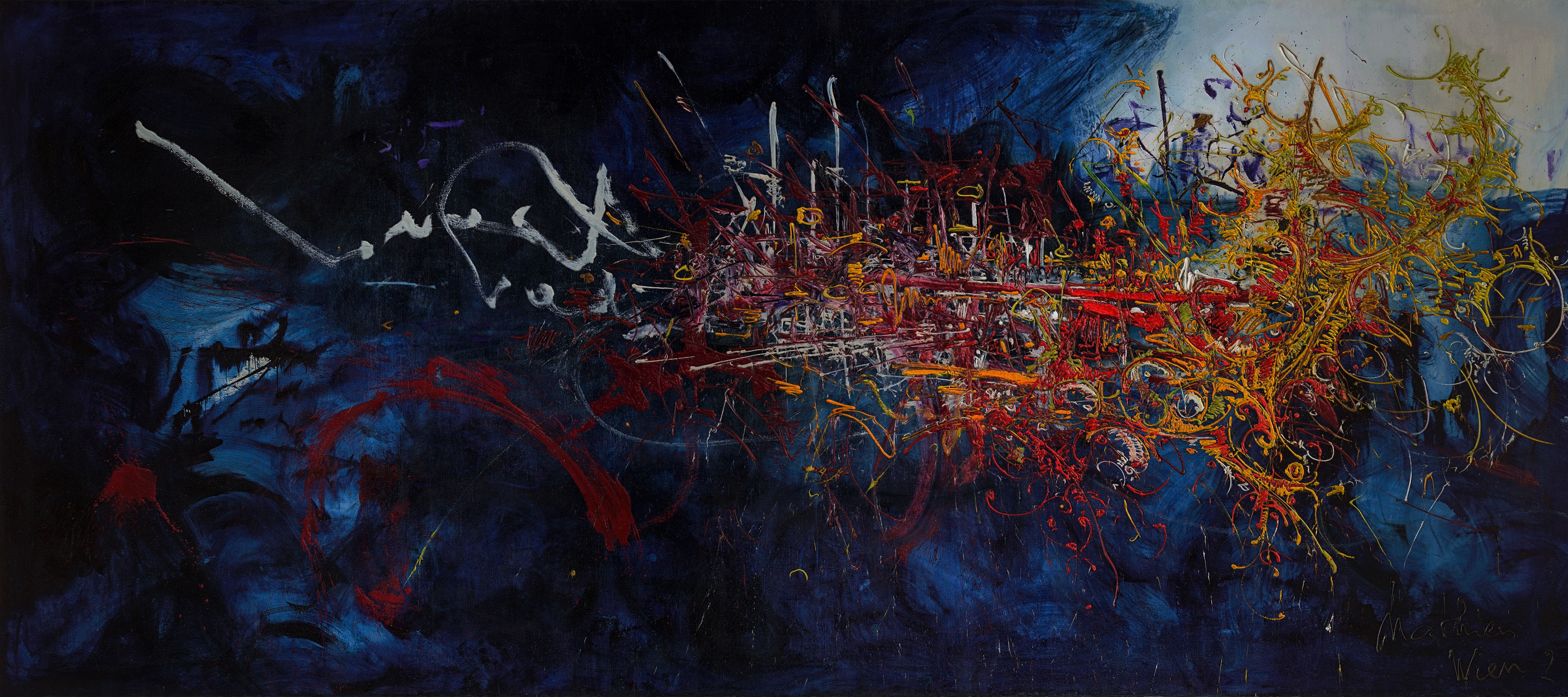

As an expert in Italian and American art, Franck Prazan could have branched out into other spheres. Especially because ‘in 2004, being accepted to Basel was essentially mission impossible for a gallery like ours! The work of our artists, was considered to be really rough painting, it was “anachronistic”.’ He decided nevertheless to keep following in his father’s footsteps. ‘I analyzed it strategically: If, in the secondary market, you’re not hyperspecialized, you are doomed to disappear. Only expertise can give you access to sources.’ By sources, he means artists’ families and public auctions. ‘We’re identified as “mono-specialists”. Gradually as opportunities arise, collections come together, until eventually a whole show becomes possible,’ he explains. ‘It took us eight years, for example, to gather all of the Georges Mathieu that we exhibited at Paris+ par Art Basel.’

Very quickly, he put art fairs at the heart of his strategy. He joined the Biennale des Antiquaires in Paris, and he exhibited at TEFAF Maastricht, Frieze Masters, London, then at Art Basel Hong Kong, and finally Art Basel in 2016. The gallery started to take off. Gradually, collectors came from all over Europe, including Switzerland (the Fondation Gandur pour l’Art, based in Geneva, is one of his best clients), but also from Taipei, where collectors went crazy for Pierre Soulages and Zao Wou-Ki, as well as from the United States and Brazil.

Thanks to his long-term work, artists that for so long had been ignored were making their comeback. Georges Mathieu is a case in point. ‘With his label of pseudo-official painter, Mathieu seemed almost satanic when I took over the gallery. Now, we are starting to understand that he was really at the forefront of a new artistic field with his work codifying lyrical abstraction.’ Franck Prazan is candid, observing that the painter quickly wasted his talent on 10-franc coins and posters for Air France: ‘From 1963, he supplied a market that was very in demand, but not only with good work – far from it.’ But no matter: He has let other people take over, in particular Perrotin, which now works with the artist’s estate. Is he scared of the competition? ‘It creates a continuity rather than a rivalry,’ he says pragmatically. ‘Estates don’t interest us, it usually involves unsold work, later periods than the ones that we’re focused on. Galleries on the primary market are better at managing this heavy flow of works than we are.’ It doesn’t stop him, of course, from doing business with heirs, particularly with the Masson, Estève, and Manessier families. ‘But I only buy if I am able to choose,’ he says. Prazan is also very close to the de Staël family and worked closely with them for a retrospective at the Paris Museum of Modern Art this year. But he says he is unable to deal with paintings that he wouldn’t want to keep.

Often, he chooses to represent an artist only over a certain period. ‘For example, I make a distinction between the final [Hans] Hartung – fantastic – and Hartung’s later work in the 1970s, which I ignore.’ For Jean-Paul Riopelle, only the 1949–1955 period interests him. When it comes to Alfred Manessier, Maria Helena Vieira da Silva, Fautrier, and Soulages – these are the rare artists that he is willing to work on across their entire career. ‘These are strong positions, but the market agrees with us. Our clients come to us because of the subjective choices that we make. It’s up to institutions to pay attention to the weaker parts of an artist’s career, not us.’

Emmanuelle Lequeux is a journalist based in Paris.

English translation: Catherine Bennett.

– Published courtesy of Art Basel

Leave a Reply