The burying ground looks like an abandoned lot.

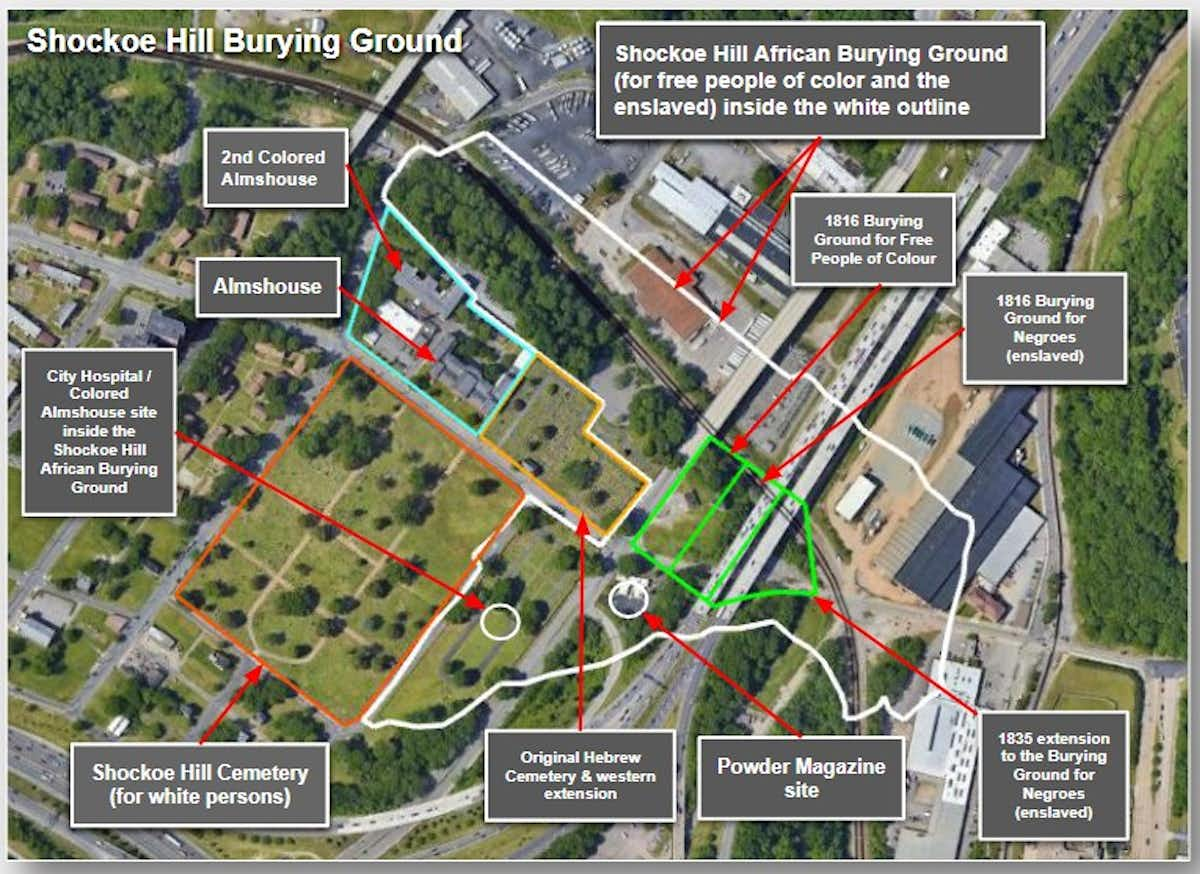

Holding the remains of upward of 22,000 enslaved and free people of color, the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground in Richmond, Virginia, established in 1816, sits amid highways and surface roads. Above the expanse of unmarked graves loom a deserted auto shop, a power substation, a massive billboard. The bare ground of the cemetery is strewn with weeds.

In contrast, across the way sits Shockoe Hill Cemetery. Established in 1822, it remains a peaceful cemetery with grass, large trees and bright marble headstones. This cemetery was created for white Christians.

I am an archaeologist who studies how the past shapes public life. Several years ago, I wrote with colleagues about the legacies of stolen human remains of African Americans in museums. During this time, I learned more about how African Americans often had to bury their dead in unsanctioned spaces that received few protections.

As I dug into this history, what struck me the most was that the different treatment of African Americans in death paralleled their long mistreatment in life. Places like Shockoe have not been accidentally forgotten.

Although its purpose has endured and graves survive, Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground, the largest burial ground for enslaved and free people of color in the United States, has witnessed deliberate acts of violence. As the historian Ryan K. Smith writes, Shockoe “was not, as some would say, abandoned – it was actively destroyed.”

African burying grounds found and lost

This issue of protecting Black cemeteries first came to popular attention in 1991, when the African Burial Ground in downtown New York City was rediscovered and nearly obliterated by a construction project. It was preserved only through the valiant efforts of African American leaders and scientists.

In recent years, similar threats to Black cemeteries and questions about preservation have been reported at the Whitney Plantation in Louisiana, the Morningstar Tabernacle No. 88 in Maryland and a rediscovered graveyard in Florida, among many others.

Like these other cemeteries, the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground has long faced constant perils, from grave robbing to construction projects.

Lenora McQueen, whose ancestor Kitty Cary was buried there in 1857, has been leading the effort to protect the cemetery. McQueen’s tireless work – like the efforts needed at any disregarded Black cemetery in the country – has ranged from collaborating with city officials to purchase part of the site, establishing a marker and mural, and assembling a team to earn the burying ground the recognition of the National Register of Historic Places.

Smith has detailed how, ever since Richmond’s founding in the 1730s, people of European and African descent in the city lived divided lives. By the early 1800s, officials formalized different cemeteries for Richmond’s different ethnic and racial communities.

A 1-acre cemetery for free Black people and another one for enslaved people were situated near the city poorhouse and gunpowder depot. Yet, these grounds were hallowed to the African American community. Burial rituals included long processions, biblical-inflected homilies, spirituals and public displays of grief.

However, the violations of these graves were easy enough. The cemetery was neither fenced nor formally tended. In the 1830s, medical schools began robbing the burying ground for cadavers. At the close of the Civil War, retreating Confederates exploded the gunpowder magazine, reportedly destroying a section of the cemetery.

City officials formally closed the cemetery in 1879, and the site’s systematic destruction began, despite constant objections of Black residents. Road and construction projects cut through the burial grounds. An African American editor at the time denounced the “people who profited by the desecration of the burial ground … when graves were dug into, bones scattered, coffins exposed and the hearts of the surviving families made to bleed by the desecration of the remains of their loved ones.”

In the years that followed, a railroad track and an elevated highway were built on portions of the cemetery. In 1960, Richmond city officials sold a portion of the burying ground to Shell, and a gas station was built atop the remains of human beings.

The struggle to preserve Shockoe

In 2011, the Virginia Department of Historic Resources conducted a survey to determine the eligibility of the deserted auto shop for the National Register of Historic Places. It did not even consider the history of the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground beneath and around the building as part of the site’s evaluation.

Six years later, McQueen learned that her ancestor was interred at the burying ground. Horrified by the cemetery’s state of disarray, she became its leading advocate. Eventually, McQueen put together a team of scholars and preservationists to pursue their own study of the site’s eligibility for the national register. They found the cultural landscape – the traces of human activity that give a place its history and meaning – to be highly significant.

Additionally, the site’s history of destruction was a vital record of the unequal treatment shown toward Black burying grounds in the U.S. The team formally pursued its own nomination to the National Register of Historic places.

In 2022, Shockoe Hill Burying Ground Historic District was successfully listed is on the national register.

Even with this success, the threats continue. Being listed on the national register provides prestige, grant opportunities and reviews for federal projects, but few guaranteed protections. In the same year Shockoe was listed on the national register, utility lines were installed in the area without consulting heritage officials.

A high-speed rail project, if implemented as planned, could violate the cemetery’s historical landscape. Designs for a memorial, while well intentioned, might further harm the site and threaten its national register status if it is not treated as a cemetery with graves.

What the Shockoe Hill African Burying Ground reveals is the need for the U.S. to provide dignity to all its citizens, in life and in death. A cemetery does not need famous inhabitants or marble tombstones to be significant.

As McQueen has said of her ancestor’s eternal resting ground, “Burial spaces are sacred.”![]()

Chip Colwell, Associate Research Professor of Anthropology, University of Colorado Denver

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.

Leave a Reply