Willow Village is a community planned for a 59-acre site in California’s Silicon Valley, between Menlo Park and East Palo Alto.

It will have housing, offices, a grocery store, a pharmacy, and its developers say, maybe even its own cultural center.

There’s one notable thing about Willow Village that makes it different from other new communities in America: It is being developed by Facebook.

Willow Village evokes “company towns” of the past, once built by corporations to both house and keep tabs on employees. And projects like Willow Village also follow the legacy of utopian communities in the United States.

American history is filled with towns, conceived and built to realize specific theological worldviews, at times linked with faith in capitalism and the power of technology. Like these utopian communities, Willow Village speaks of its founders’ desire to correct imagined social problems by reinventing social life.

But those earlier utopian communities and company towns foundered, either from labor strife or lack of leadership. Will the same thing happen to Facebook’s experiment in designing and building a community?

And considering the many recent controversies Facebook has had with its social network, do we want them controlling our physical environments, too?

Improving on human nature

I am a scholar who has researched digital culture. As I’ve argued elsewhere, social media companies often position their projects as socially beneficial, as if human nature could be perfected through engineering and planning.

Juan Salazar, a Facebook public policy manager, claims that Facebook’s goal for Willow Village “is to strengthen the community”: “We want a more permeable relationship, where we engage more. The parks, the grocery store, are places to congregate together, to build a sense of place.”

Salazar’s comment implies that, without Facebook’s corporate engineering, these spaces for community would not exist on their own, or at least can be improved by corporate intervention. Planning, policy and even some government functions, then, would be transferred from democratically elected officials to private corporations.

Facebook proposed Willow Village in 2017 as a redevelopment of the former Menlo Science & Technology Park. Initially named the “Willow Campus,” Facebook’s community, which will include 1,500 apartments, is a response to the exorbitant cost of living in Silicon Valley. The median home price in the San Jose metro region in 2017 was US$1,128,300.

Willow Village is one of a number of planned communities that tech firms want to build to provide housing, primarily for their own employees.

Google plans to build between 5,000 and 9,850 homes on its property in Mountain View, near Menlo Park. Google’s community will include retail stores and entertainment.

Consequences questioned

There are many criticisms of these plans.

As The New York Times has reported, Willow Village will most likely displace a largely Hispanic community, one of the poorest in Silicon Valley.

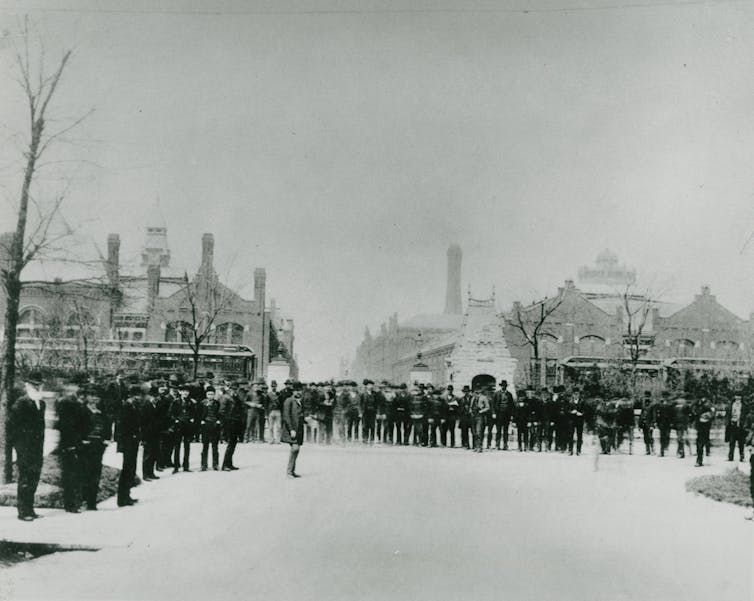

Plans like Facebook’s and Google’s evoke cities and neighborhoods built by, for instance, railroad magnate George Pullman or chocolate tycoon Milton Hershey. While envisioned as communities with “no poverty, no nuisances, no evil,” in Hershey’s words, these cities in fact were characterized by strikes, private police forces and bloody clashes between workers and management. Similar stories can be told of other company towns, such as Gary, Indiana, or Lowell, Massachusetts.

Silicon Valley has long been hostile toward organized labor. This leads to concerns that Google and Facebook’s new communities could engage in versions of the anti-labor practices of company towns throughout history, updated to include digital surveillance and technological means of control.

Will connecting solve problems?

Company towns have never lived up to their mission of social perfection.

Yet Facebook and Google, like many tech companies, say their purpose is socially beneficial. John Tenanes, Facebook’s vice president for real estate, told The New York Times, the apartments in Willow Village “are a starting point.” He added, “I would hope we could do more. We’re solving a problem here.”

While this quote seems innocuous, it reflects what critic Evgeny Morozov has termed “solutionism.” The goal of solving problems isn’t the problem. Rather, it’s that technological solutions circumvent governmental institutions.

Says Morozov: “We are abandoning all the checks and balances we have built to keep our public officials in check for these cleaner, neater, more efficient technological solutions.”

Specifically, social media companies often frame social problems as a lack of connectivity, which can be solved with technologies designed to foster social interconnection. In my research, I’ve followed how attitudes toward social connection have changed over time in American history.

As I charted this history, I found that this perspective draws on beliefs that emerged in the wake of the Great Depression. Prior to the Depression, social, technological and economic connectivity were feared by many Americans as a socialist means for restricting individual freedom. In a nutshell, connection meant organizing, which meant socialism.

It was only after the Depression that networked connection became widely imagined as a solution to a range of social ills.

But social connectivity was not always feared. Willow Village shares an outlook with other, much earlier, planned communities: A utopian worldview has been central for countless communities and towns founded across America in the 1800s. These towns were precursors of the larger, post-Depression embrace of connectivity. Many of these communities were isolated reactions against capitalism, founded with socialist guiding principles.

This isn’t to suggest that all of these communities were socialistic, however. A community closer to Willow Village can be seen in the model of the Oneida community in upstate New York, where capitalism was central to its utopia and was a way of distributing Christ’s energy to others, via the market.

Most of these utopian communities failed. Whether because of internal disputes over religious orthodoxy or money, few managed to last longer than a few years. Most that did endure only did so until their founder’s death. Without an authoritative social vision, the community fell apart.

So there’s been a long history in which social vision is shaped into ways of planning and living in America. The actual existence of these communities, however, has been marked by struggle and conflict.

The modern utopian community

In my research, I’ve argued that connecting via social media and circulating personal information is imagined as a means to achieve a kind of spiritual perfection today. Being connected to Facebook at all times, not just via their platforms, is imagined by those in Silicon Valley – sometimes implicitly, sometimes explicitly – to have an intrinsic social benefit.

Given how these visions are now shaping the planning of actual communities, this can be thought of as a reinvention of citizenship – and not metaphorically.

Facebook and Google are proposing, and occasionally entering into, partnerships with local governments, taking over numerous tasks once the responsibility of elected officials. This includes not only dictating housing policy, but also, for example, funding the police. Social media corporations are working to act in the roles once held by the state and government.

The threat is not that this is new. The legacy of company towns, for instance, tells us that corporations have often tried to subvert democracy with their own “governmental” agencies.

The problem is that this model now reflects a view popular in Silicon Valley that sees tech companies as progressive agents solving problems beyond governmental oversight. This worldview, in part, descends from the long history of utopian communities.

![]() We will most likely see more of these projects and partnerships. But here’s the catch, and the threat: When they do this, elected officials cede power to companies that are not, like them, democratically accountable.

We will most likely see more of these projects and partnerships. But here’s the catch, and the threat: When they do this, elected officials cede power to companies that are not, like them, democratically accountable.

Grant Bollmer, Assistant Professor of Communication, North Carolina State University

Leave a Reply