Today a desert – as far as the eye can see. However, anyone looking more closely will discover hundreds of images carved into the rock. This ancient Egyptian graffiti attests to the fact that a new claim to sovereignty emerged here on the periphery over 5,000 years ago. One of these kings was known as Scorpion. He demonstrated his power with portrayals of himself as a divine ruler and with brutal depictions of violence. Together with Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr, Egyptologist Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz from the University of Bonn has now published in his book the latest findings concerning the visualization of claims to sovereignty in pre-Pharaonic Egypt.

The landscape in the desert around Wadi el Malik to the east of Aswan has so far been the subject of little archaeological research. There are hundreds of images here and some particularly early hieroglyphs, which originate from the time before the dynasties from the late fourth millennium BC were formed. “The Egyptian state emerged during this period,” says Egyptologist Prof. Dr. Ludwig Morenz from the University of Bonn. “This was the world’s first territorial state.” It has been known for some time that the north-south extension of Egypt at that time was already around 800 kilometers.

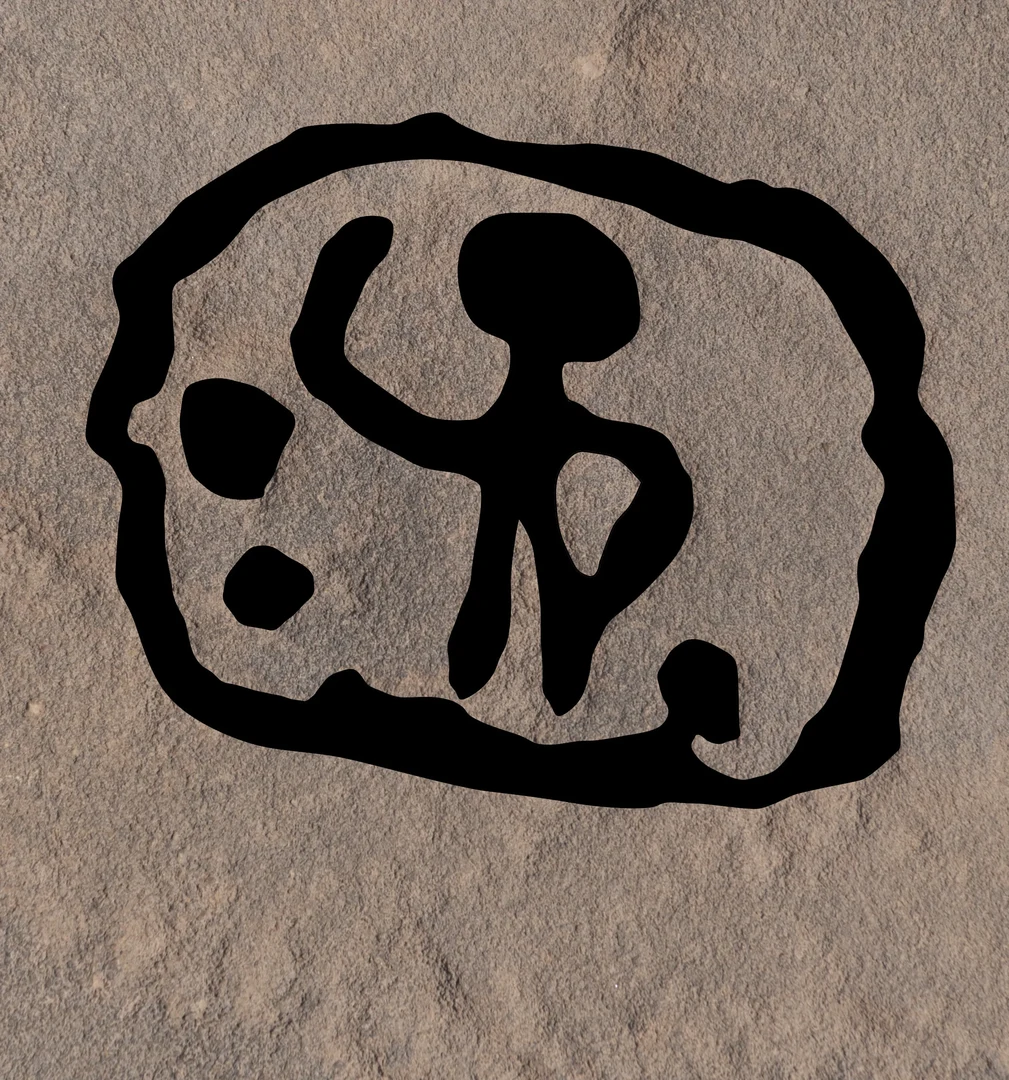

One of the rulers over 5,000 years ago bore the name Scorpion. Little is known about him. His name is written alongside three other hieroglyphs in a rock inscription from a side wadi of the Wadi Abu Subeira to the east of Aswan: “Domain of the Horus King Scorpion.” A circular hieroglyph indicates that it is a place name. Morenz interpreted the inscription as the “world’s oldest known place name sign” several years ago. This news caused a sensation and was considered newsworthy by many media outlets. Alongside Mohamed Abdelhay Abu Bakr, he is now presenting his latest findings relating to this rocky landscape with its millennia-old inscriptions in his new book, “Culture and Power in Pre-Pharaonic Egypt, Visualizing Claims to Sovereignty in the Socio-Cultural Periphery of Wadi el Malik and Wadi Na’am during the Fourth Millennium.”

Royal rock art tableau

Scorpion was not the first ruler and is not the only person marked on the rock. Morenz speaks of a “royal rock art tableau”, as several rulers who reigned one after the other are linked here with their names and the image of a distinctive animal in a kind of matrix. Alongside Scorpion, the Protodynastic kings depicted also include King “Bull”, who reigned before him. The royal line begins with King Horus-Falcon. “Most early ruler names refer to dangerous animals that embody authority,” says the Egyptologist. Even before these rulers was “Scolopendra,” named after the venomous, and thus dangerous, centipede. This ruler’s name was discovered by Morenz.

Over 5,000 years ago, the region was a transit area for expeditions, contained mineral resources, and was also a sought-after hunting ground in those wetter times. “It is actually all about a grandiose presentation of the claim to sovereignty,” says Morenz, referring to the abundant rock carvings in this region. Wadi el Malik lay in the socio-cultural periphery of the Nile Valley and was evidently claimed as the domain for the still very new territorial state at that time.

The rulers were not simply ‘gods,’ but instead portrayed themselves as earthly representatives with a connection to the main gods. In the case of Scorpion, Bat and Min were the central divine couple in the Nile Valley in the second half of the 4th millennium. Bat was understood to be a celestial cow – depicted as a cow’s head with stars – and Min a man. Morenz: “They formed a divine couple, with Bat associated with the fertile land along the Nile and Min with the peripheral regions as a kind of hunting god.”

“Pharaoh-fashioning” as a divine portrayal

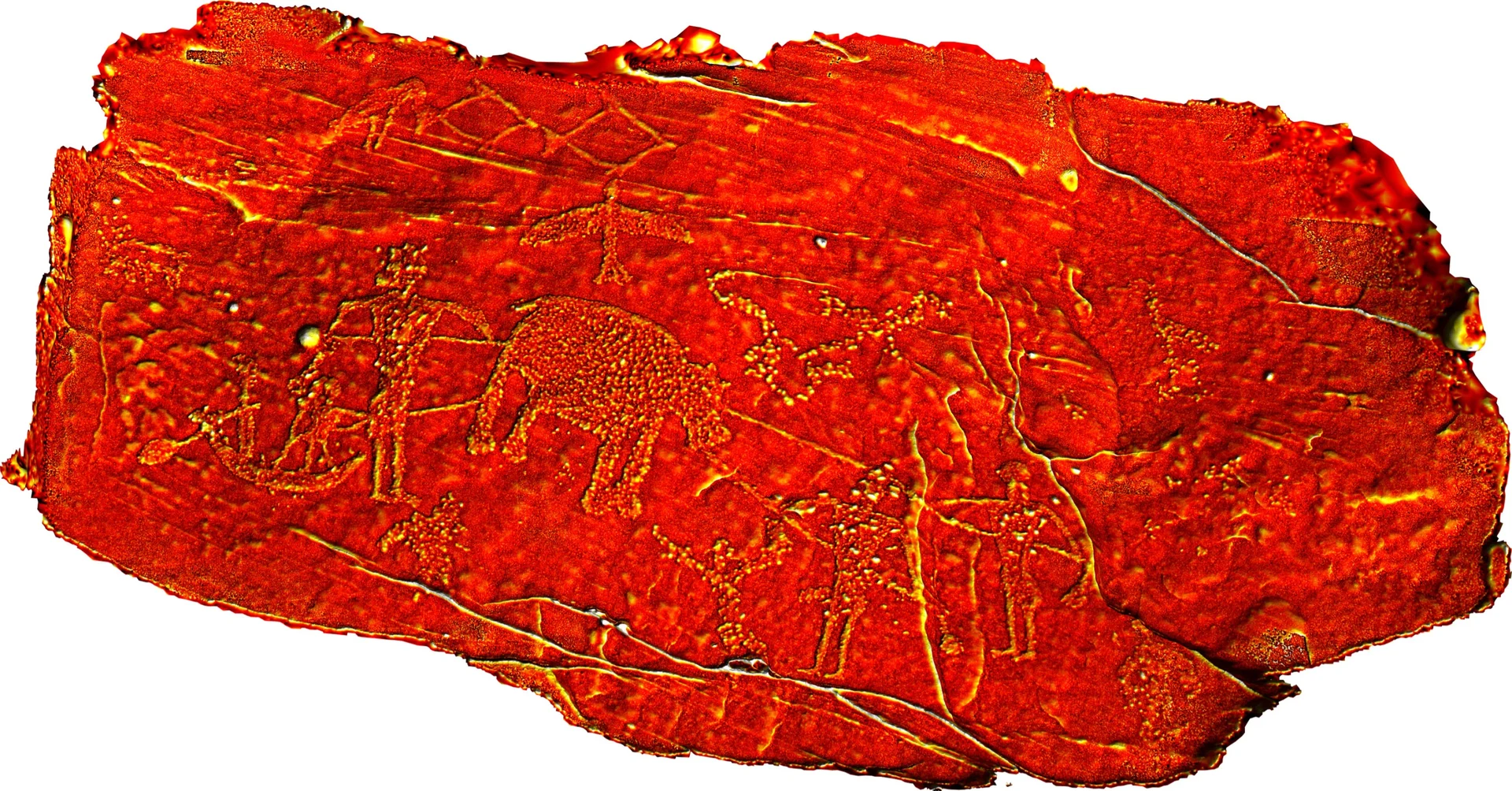

The Egyptologist refers to this as “pharaoh-fashioning,” by which he means the visualisation of distinct rulership. “The territorial state was still brand new at that time. As a result, ways to present such an unusual claim to sovereignty in images and text had to be found,” he says. Depicting victory over enemies was central to the ideology of sovereignty. Dominance was visualized within the rock art in scenes of violence – using the striking pattern of depicting oneself in stone as invincible while showing one’s enemies as small, subjugated figures. “The most extreme scene is the one showing the ruler trampling an enemy, with two decapitated heads visible in the background,” says the Egyptologist, indicating an image that he has recently discovered and interpreted.

The ‘boat of the gods’ carved into the rock also relates more specifically to religion. This is an extensive depiction of a boat hauled by 25 men. According to the researcher, the boat represents sacred processions that established the link between regions, specifically the Nile Valley and the desert wadi in this case.

New digital methods

The researchers used new digital technologies that analyze numerous photographs taken from various angles with a high level of computing power to reveal contours of the rock carvings that cannot be seen on site. The Egyptologist from the University of Bonn believes that research in this region is still in its infancy. “This is an important region when it comes to our understanding of the emergence of the state at the socio-cultural periphery in the late fourth millennium,” says Morenz. “We generally know much less about this than about the cultural centers.”

The researcher is hoping for a large-scale project aiming at further archaeological research within this region. When it comes to rock carvings, it is not only about the depictions themselves but also, as in an overall work of art, about their positioning in the surrounding landscape. “I consider this so important that this hot spot should also be made accessible to interested parties with tours and a visitor center,” says Morenz.

Leave a Reply